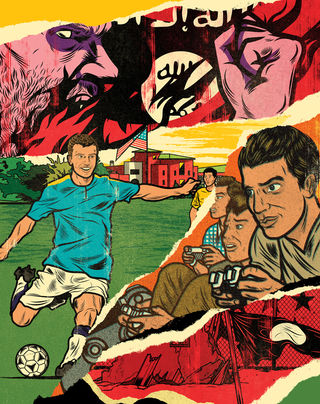

How Did Two All-Americans Fall In With ISIS?

These promising college students sank into the rabbit hole of extremism, and were ready to leave family, friends, and country behind. Everyone was baffled.

By Mike Mariani published November 7, 2017 - last reviewed on November 16, 2017

On a 90-degree day in August 2015, two FBI agents arrived at the house of Oda and Lisa Dakhlalla in Starkville, Mississippi. Oda, originally from the West Bank, was active at the mosque just across the street from their home. He also tutored Mississippi State students in calculus and trigonometry, earning him the nickname Yoda. For years the couple ran the family's restaurant, Scheherazade's, named after the ingenious storyteller in One Thousand and One Nights. Lisa, a Muslim convert who grew up in New Jersey, was known in Starkville as "the hummus lady." She made her recipe for friends and sold the dip at a local farmers market. Lisa's cooking was so popular that the couple hosted dinners attended by mayors, police chiefs, attorneys, students, and faculty from around the world.

On several occasions, in fact, the Dakhlallas had served dinner to these two agents. Worried about perceived threats to his mosque, Oda had often called the FBI field office in Jackson, and he and his wife had become acquainted with a few of its agents; they became friends of the family. So when they told the Dakhlallas the news about their youngest son, Muhammad, Oda thought they were joking. "Come on guys!" he said. "You are pulling my foot! Let me fix you something to eat." Lisa, however, saw the expressions on the agents' faces and sensed that this was not a joke. The agents explained that they had intercepted the couple's son and the woman accompanying him, Jaelyn Young, at the Golden Triangle Regional Airport in Columbus, Mississippi, earlier that morning. The couple were at the gate about to board Delta Airlines Flight 5073 to Istanbul; from there they planned to cross the border into Syria. The agents informed the Dakhlallas that their son had been arrested for trying to join ISIS.

It took a long time for Oda Dakhlalla to realize that the FBI agents were not, in fact, playing a bad joke on him: His 22-year-old son planned to meet, at Istanbul's famous Blue Mosque, ISIS handlers who would then ferry Young and him to Syria. There, they would join the terrorist organization's self-proclaimed caliphate.

Oda could be forgiven for his disbelief. Muhammad, called Mo by family and friends, had a 4.0 GPA at Starkville High School and had graduated cum laude from Mississippi State just a few months prior to his arrest. He had been accepted into the school's graduate program in psychology and was supposed to start classes about a week after he was picked up at the airport. While Dakhlalla studied hard, he also hung out with friends, played pick-up soccer, and immersed himself in video games like Final Fantasy. While he didn't drink—his father forbade it—he still attended house parties at Mississippi State. Altogether, Dakhlalla was a recognizably American kid: gaming nerd, soccer player, industrious student, and respectful son.

That same morning, three hours from Starkville in Vicksburg, Mississippi, another pair of FBI agents were making an equally grim house call—one met with similar incredulity. When the agents informed Leonce and Benita Young of their daughter's arrest, Benita, a school superintendent, told them, "I think you have the wrong house." Jaelyn Young, who was just shy of 20, also had a strong academic background. She hadn't just been an honor student at Warren Central High School, though. She was a talented gymnast, a cheerleader, part of the homecoming court, and a member of the robotics and math clubs. She was a textbook well-rounded overachiever, the kind of teenager who throws her work ethic into an array of pursuits. At her sentencing a year later, she would recount her earlier aspirations of attending medical school to study neurosurgery.

How did these two gifted and hardworking young people come to their decision? Family, close friends, and acquaintances remain bewildered. Even more baffling was Jaelyn's age—she was still a teenager. Only about one in 10 individuals who are tried on ISIS-related charges in the United States are female, and the average age of all recruits is 27. There is also the abruptness with which both Young and Dakhlalla careered into lives that bore little resemblance to the ones they had so recently led. In just a few short months, in the spring of 2015, they would go from being promising college students to self-radicalized extremists ready to leave families, friends, and country behind.

ISIS officially declared itself a caliphate in June 2014. Since then, 111 men and women in the U.S. have been charged in connection with the terrorist organization. Sixty-two of these individuals—including Young and Dakhlalla—have been convicted. Spring and summer of 2015—the same period in which the couple was radicalized—saw a record number of Americans arrested on ISIS-related offenses. It was the zenith of recruitment in the U.S., and the young couple's radicalization mirrored this timeline exactly. To some, their story is a cautionary tale of how social media and online recruitment methods could sway seemingly grounded young people toward dark sympathies.

The Big Bang Theory

In the fall of 2013, as a freshman at Mississippi State, Young went on a mission trip to Memphis sponsored by the Wesley Foundation, the college arm of the United Methodist Church. On the bus she sat next to Andrew Smith,* a junior engineering major from Greenland, a small town in the Mississippi Delta. After getting to know each other during the trip, they started hanging out back at Mississippi State. They watched movies like District 9 at Smith's apartment, and they texted over Christmas break. By the time Young and Smith returned to school for the spring semester that January, they were in the early stages of a relationship.

But Smith was starting his senior year, and his demanding course load meant he couldn't always give Young the time she seemed to need. As the term progressed, they started to drift apart. But the following fall, Young and Smith continued seeing each other. By October, she was spending more and more time at his off-campus apartment, and he even gave her a key.

Smith's college friends included his Vietnamese roommate, two Indian students, an African-American student, and Dakhlalla. "We had a pretty diverse group," Smith says. The friends, however, hardly evoked a fraternity atmosphere. They all focused hard on their studies and would get together at Smith's to play board games like Settlers of Catan and King of Tokyo. "It was like Big Bang Theory," says Jane Harmon, a close family friend of the Dakhlallas. "None of them were cool. They played computer games, and they were really smart."

That fall term, Young began talking with Dakhlalla. While Smith was busy finishing his coursework in his final semester, she and Dakhlalla grew close. By the end of October, the two were hanging out at her apartment, apart from the rest of the group.

Losing Her Religion

Young spent her first two years at Mississippi State experimenting with different religions. In Vicksburg, she was raised in a devout Christian household. Her family attended the nondenominational Triumph Church in town, where her mother taught Sunday school. Jaelyn and her younger sister, Kaylin, were expected to attend Sunday School every week and participate in the children's ministry, which was held on Wednesday evenings. The family's pastor, Michael Wayne Fields, even testified at Young's sentencing, telling the court she was an "outstanding young lady" who had "never given her parents a minute's problem."

During her freshman year at Mississippi State, Young began showing interest in other faiths. She spoke regularly on the phone with her Creole grandmother, as often as several times a week. Young was fascinated by her grandmother's esoteric spiritual beliefs, which included elements of Vodou (voodoo). Young even kept spices and bundles of grass in an old milk crate.

Toward the end of her freshman year, Young's grandmother died and she was spiritually cast adrift. She started searching out other faiths. That summer she began studying Hinduism and Buddhism. Beyond that, Young toyed with Wicca. During her sophomore year, she took an interest in Islam. Like the other major monotheistic religions, Islam is dense with history, doctrine, and text. In many ways, it's too forbidding for autodidacts and not the kind of faith that one can master by cobbling together Wikipedia entries. She needed someone who could guide her.

Dakhlalla seemed a perfect fit. Low-key, unassuming, and a bit diffident, he was the antithesis of Young's intensity and zeal. He also had had few experiences with women. His father Oda was extremely strict about dating and, following religious tradition, forbade any physical relationship before marriage. "Mo was very naive when it came to women," Harmon says.

As fall turned to winter, and things continued to deteriorate between Young and Smith, she shifted all her attention to Dakhlalla. He was, after all, the one who always seemed to be there for her. For his part, he was smitten. The two started dating toward the end of 2014. By January, things were moving in a direction that perhaps neither fully understood.

The Rabbit Hole

By winter, some of Young and Dakhlalla's friends had developed an aversion to her. She had, after all, started seeing him in the waning days of her relationship with Smith. Also, her fierce and intense nature could be off-putting. Through ambivalence or tacit disapproval, the couple became ostracized from the larger group. By February, Young had met Dakhlalla's parents, in part because of her fast interest in Islam; Oda's instruction could far exceed his son's. On her second visit to Starkville, Young converted to Islam, reciting the Muslim profession of faith, the shahada.

Once officially a Muslim, Young's enthusiasm gathered momentum. While she learned how to pray and recite the Quran, she devoured YouTube videos on Islam. She began with educational videos but eventually stumbled upon one that documented the rise of ISIS. It showed stark footage of a bloodied and war-torn Syria and depicted the group in a heroic light. Emotionally charged by the video, she began to seriously consider going to Syria to help ISIS and make a difference.

That video turned out to be something of a White Rabbit, luring Young down a tortuous hole, and Dakhlalla followed. All logic was abandoned and mainstream narratives of ISIS were treated as nothing more than pro-Western propaganda and American lies. More videos followed, accessed through links on Twitter. By spring, Young was openly supporting the Islamic State on social media. Soon, she started corresponding with a militant "sister"—who was actually an undercover FBI agent.

In June, just six months after they started dating, Dakhlalla and Young held a nikah—the Muslim marriage ceremony. To guests, the wedding felt haphazard, as though it had been put together in a few days. "It seemed as if they decided within 48 hours, 'Hey, let's get married,'" says a family friend who attended the ceremony. In a traditional nikah, the bride is given away by a guardian, usually her father, but Young's was not to be found. Leonce Young's no-show was a blow; the couple had asked him to sign the religious contract, but he refused and did not attend.

One of Dakhlalla's brothers feels that the slapdash ceremony betrayed a larger plan. Protective of his infatuated brother, he believes that Young "was using Mo as a way to get to Syria. As a woman, if you're going to be super-fundamentalist, you need to have your guardian traveling with you."

The wedding was rushed enough that neither Dakhlalla nor Young obtained a marriage license. This detail proved critical after the arrest: Because they were not legally married, they were tried separately.

The night after the wedding, at a reception hosted by one of Dakhlalla's brothers, the newlyweds were subjected to criticism from some women who regularly attended the mosque. They suggested that the wedding could have been better planned. The women had known Mo for most of his life and thought of him as family. As a result, their criticism was largely directed at Young.

She felt bullied, and her chagrin further isolated Dakhlalla from his community. Most important, according to Mo, her feelings of alienation strengthened her resolve to leave.

Meanwhile, Young and Dakhlalla were both delving deeper into ISIS's online underworld. While watching YouTube to learn about Islamic law, they found videos of Anjem Choudary, the British hate preacher arrested in 2015 for inviting support for the terrorist group. According to court documents, Young turned increasingly to propaganda videos and shared them with Dakhlalla. Her sense of morality was changing too. At one point, Young showed Dakhlalla a video of ISIS throwing a man accused of being gay off the roof of a building. When the fall doesn't kill him, he's stoned to death. Dakhlalla's response was equally alarming; his attorney claims that he assumed that the people throwing homosexuals off buildings were "the radicals [within ISIS] and not the norm." For Dakhlalla, his susceptibility lay in his need for female companionship.

During her sentencing, Young recalled removing "posters of my favorite shows and music artists, some of which I had listened to for as long as I can remember," because they were no longer compatible with her new faith.

One night, after Dakhlalla dropped Young off at her parent's house in Vicksburg, he went to Jackson to stay with his brother for the weekend. When his sibling found him discussing extremism with Young on Facebook Messenger, he tried to intervene. He hoped to dissuade them from the dark path they seemed headed down. Appealing to them on theological grounds, he showed them the "Letter to Baghdadi," a refutation of ISIS written and signed by more than a hundred Muslim scholars from around the world. The brother hoped to demonstrate how the radicals were not only failing to uphold religious law but were breaking it in dozens of ways. It was a valiant but futile effort, according to the brother, fundamentalism had taken hold.

Criminal Intent or Thought Crime

It's open to question whether one can draw generalizations from individual cases of attraction to cults, including ISIS. "There's been an awful lot of research trying to find a psychological profile, or a demographic one, of a vulnerable person," says Alexandra Stein, an expert on cults and totalitarian movements at the Mary Ward Centre in London and the author of Terror, Love, and Brainwashing. No profile has been definitively established. If there is a pattern, it's not the one we might think. Instead, she says, the common thread might be a "situational vulnerability." This usually takes the form of a transitional period—graduating from college, moving, changing careers—during which one's influences and social network are in flux. "These are normal transitions, where people may be going from one set of moorings to another."

Alice LoCicero, who has studied terrorism around the world for 15 years and is currently president-elect of the Society for the Study of Peace and Conflict, cautions even more strongly against broad characterizations of potential terrorist recruits. "If you look at all of the literature," she says, "including studies funded by the federal government, it says the same thing: We have no idea who's going to become a terrorist."

Her reservations don't stop there. LoCicero worries that a law enforcement strategy focused primarily on social media creates a slippery slope for what we view as terrorist-related crimes. "I have grave concerns about criminalization of thought," she says. Specifically, she's wary of the online spaces where young people articulate what may be fleeting extremist sympathies, only to be suddenly supplied with the instruments to act on them—by a U.S. intelligence agency. These kids, she argues, "haven't really, on their own, done anything and might not even be capable of doing anything had they not been aided by the FBI."

By the time they married, in early June 2015, Young and Dakhlalla had each begun tweeting with FBI agents posing as ISIS members. In a conversation on May 29, Young told an undercover agent that she was preparing for hijrah, a term for traveling to the caliphate. "I have a hijrah partner and we are planning to leave before August," she confided. Just days later, Young was introduced on Twitter to another FBI agent, this one posing as a facilitator. She told him, brazenly, "I need help crossing from Turkey to Syria with my hijrah partner," and explained that she was "skilled in math and chemistry and worked at an analytical lab at my college campus."

Around the same time, another undercover FBI agent reached out to Dakhlalla, who wrote back: "I am good with computers, education, and media. What could I contribute to Dawlah [another term for ISIS]?" Dakhlalla also questioned his contact about what he and Young would be doing when they reached the caliphate. Meanwhile, Young shared her enthusiasm with her contact: "I cannot wait to get to Dawlah... and raise little Dawlah cubs In sha Allah."

Both Young and Dakhlalla shared a powerful distrust of mainstream Western media. They felt the media presented a biased picture of ISIS, spreading what they thought were lies about the group—that ISIS kept young girls as sex slaves, for example—while overlooking the good it was doing in a destitute, failed state that the rest of the world seemed to have forsaken. Their disdain for media coverage of the terrorist group helped facilitate their swift radicalization—and even added to their sense of purpose. Young told her contact that the U.S. "has a thick cloud of falsehoods and very little truth about Dawlah," and that her partner, Dakhlalla, wanted to work to correct these falsehoods when he got there.

The night before their flight, Dakhlalla and Young ordered pizza at his parents' house, where they were then living. They stayed up into the early morning, making final preparations. As Young continued her meticulous packing, Dakhlalla unwound on the couch, watching The Lord of the Rings. "I wasn't even close to being mentally prepared," he says. That morning, Young drove them to the airport. The 20-minute ride was eerily silent. Everything that lay ahead of them was finally sinking in, the swirling fog of YouTube videos and social media conversations suddenly cohering into something far more consequential. Dakhlalla describes walking through the airport in a daze. The pair got their boarding passes, went through security, and waited in line at the gate. When they reached the jet bridge, the FBI was waiting for them.

It's Quiet in Here

While Dakhlalla and Young were tried separately, their cases took place simultaneously. In addition to incriminating farewell letters both had written to their families, shortly after being arrested they each confessed to the FBI their plan to join the caliphate.

In her letter to her family, Young identified herself as the primary force behind their botched plan. "It was all my planning—I found the contacts, made arrangements, planned the departure," she wrote.

The couple communicated with each other through letters during their first few months in jail while awaiting trial. From behind bars, Young tried to convince Dakhlalla to corroborate her story that the two were traveling to Syria to do an expose on ISIS. Instead, he turned her letters over to the FBI and Homeland Security, who then shared them with prosecutors. "Shortly after that, she sent Mo a 'Dear John' letter," Harmon says.

Dakhlalla and Young pleaded not guilty to the charge of conspiracy to provide material support to ISIS, but in March 2016 both changed their plea to guilty. The conspiracy charge carried a maximum sentence of 20 years, so neither was eager to go to trial. At Young's sentencing, on August 11, both her parents (neither responded to requests for comment) testified on her behalf. Young's father, Leonce, who had served in the Navy and is a police officer, talked about the dozen or so tours he had done in the Middle East and the milestones in his daughter's life that he had missed—high school graduation, heading to college. Jaelyn had grown increasingly frustrated by his absence, he explained, and couldn't understand why her father, and her family, had to make such large sacrifices for their country. Even when he called her from overseas, in Afghanistan or Bahrain, time was limited and the conversations terse. "I couldn't have what we call a Hollywood conversation," he testified.

Her mother, Benita Young, also gave a sworn statement. Early in her testimony, she recalled finding cuts on her daughter's legs when she was in seventh grade. When Benita questioned her about them, Jaelyn told her, "Well, Mom, I cut myself." Benita also mentioned a call she got from Jaelyn one night while she was at Mississippi State. Young was overwhelmed, telling her mom, "I just don't think I can do it. It's too much." Her mom told her to suck it up—that it was just a couple more years, and she'd be out of there.

Together, these testimonies offered a portrait of a teenage girl varyingly troubled, angry, and socially isolated—despite all outward appearances. The judge, though, was unmoved. Young was sentenced to 12 years in prison.

Two weeks later, Dakhlalla was sentenced. His father did not speak in court, and his mother had died of cancer a few months earlier. The court-appointed defense attorney, Greg Park, attested to Dakhlalla's strong character, pointing out that the 23-year-old had raised money for charities and helped build houses for Habitat for Humanity: "You see what he has done every day of his life up until he purchased that ticket to ride that plane."

Dakhlalla also spoke at the hearing, stating that he got a lot of his information from the Internet, and felt that the ISIS videos he had seen depicted a group that was doing a lot of good helping people in a seemingly hopeless place. Assistant U.S. Attorney Clay Joyner was unsympathetic. "There's nobody not living under a rock who did not know what ISIS was doing. ISIS was not trying to hide what they were doing," he said. In remarking that ISIS had videotaped a pilot being burned alive, Joyner added: "So, to say that you're not aware of their atrocities is a bit disingenuous."

Dakhlalla was given eight years. Chief District Judge Sharion Aycock, who presided over both cases and had significant latitude in her sentencing, seemed to understand and account for the unique dynamic between the two defendants. In the sentencing, Young was depicted as the "mastermind" and Dakhlalla the dutiful tagalong, and Aycock's decisions reflected a similar interpretation.

Over the course of a handful of phone conversations with Dakhlalla (Young didn't respond to interview requests), a picture gradually emerged of two young people, both adrift, one fierce and assertive, the other impressionable and besotted. This isn't to say that they weren't both accountable for their actions; acquiescence can be just as dangerous as zealotry. But after their wedding, Dakhlalla's loyalty to Young was ironclad. A relationship that was, according to him, initially based primarily on sexual attraction suddenly had new dimensions of commitment and responsibility. "Whatever she wanted, I was down for," he says.

In its videos, the group depicted itself as a force for good—rebuilding ruins and feeding the poor, Dakhlalla says. How does he reconcile such a glowing picture of ISIS with the grizzly snuff films the group flaunted to the world? He framed these actions in terms of war; at the time, he thought the victims were "people that ISIS had just gone into battle with." (All of the content he and Young consumed was generated by ISIS, not U.S. law enforcement.)

The group's apocalyptic ideology, meanwhile, quickened the pace of the couple's radicalization. Videos and online literature convinced them that the end of the world was approaching, and a true Muslim would be in the caliphate for the end-of-days. The feeling of spiritual urgency—the beginning of the end of the world, according to the apocalyptic timeline—helps explain how Dakhlalla and Young were seduced by extremism so rapidly. Dakhlalla compares the propaganda to the pressure of a car salesman offering a discounted price for a limited time only. In the midst of a good sales pitch, anything can sound irresistible. Logical reasoning resurfaces only later, with buyer's remorse.

The catch, of course, is that the salesmen were not actually ISIS recruiters but FBI agents. Would Dakhlalla and Young's progression from teaching and learning about Islam to buying tickets to Istanbul have happened so fast, or at all, if it hadn't been facilitated by American law enforcement? LoCicero fears that the FBI's approach could be turning fanatical ideas into terrorist crimes and that it conflates social media radicalization with extremist violence. "We have no idea what the pair would have done if they had had good mentoring from people in the community and had not had the FBI encouraging them," she says. Alexandra Stein cites a theory by scholar Martha Crenshaw: People are recruited to cults and terrorism "by accident on their way to other goals." Dakhlalla desperately wanted to marry, to satisfy both his father and his own yearning for companionship. Although she is more enigmatic, Young was deeply spiritual, eager to give herself over to a religious cause. As Leonce testified at his daughter's sentencing, "Whatever she does, she puts her heart and soul into it." The temporary form their overarching goals took, though, was what mattered. Together, they had planned to join ISIS, even if neither one had ever corresponded with an actual terrorist.

At the Federal Correctional Institution in Jesup, Georgia, the prison where he is being held, Dakhlalla tutors other inmates studying for their high school equivalency tests. He's also considering getting his heating and ventilation license, so that he'll have a trade skill when he is released. The predictability and calm of his prison life, according to family friend Jane Harmon, is a welcome respite from the turbulent months leading up to his arrest. "Once you get a routine going, days fly by," he says.

Shortly after Dakhlalla's arrest, his mother and Harmon made the two-hour drive from Starkville to the Lafayette County Jail, where Dakhlalla was awaiting trial. Harmon sat at the glass partition to speak to him through the direct-connect phone. "The first thing he said was, 'Jane, please thank Dennis for me,'" Harmon says, referring to her husband, a lawyer who had represented Dakhlalla's family during the ordeal. "'I appreciate everything he's done for my family, and I want to thank you for bringing my mom today.'" Harmon, who considers herself a tough woman, felt her lips quiver. Sensing she was about to cry, Dakhlalla told her, "Don't cry. Look, I'm okay. It's quiet in here."