Loneliness

Understanding Loneliness by Exploring Connection

What psychological concept can help explain why we're lonely?

Posted February 5, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Loneliness and isolation are an epidemic in the U.S., with significant negative health effects.

- Psychologists have long studied connection through the lens of attachment theory.

- People's attachment styles are based on patterns they form with early caregivers that are carried forward.

We are in the middle of a loneliness epidemic. In 2023, the U.S. surgeon general released a report titled “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” which described the serious health risks associated with being lonely. Lonely people are at substantially increased risk of developing heart disease, of having a stroke, and of developing dementia. It’s even linked to having a shorter lifespan.

So what do we do about loneliness? The surgeon general makes broad policy recommendations, such as increasing the number of places where people can connect and socialize (e.g., public parks, libraries), creating “pro-connection” policies like making public transportation easier to access and paid family leave more available, and re-evaluating our relationships to social media. At an individual, psychological level, I’ve been thinking more deeply lately about another aspect of our connection with others: our attachment styles.

Research on attachment grew out of pioneering research by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, who were studying the way that children relate to caregivers. They researched the way that infants bond with their primary caregivers (often, but not always, their mothers), finding that the infants had different ways of interacting with them.

Mary Ainsworth introduced the “strange situations” task to see how infants would react to being reunited with their caregiver after a period of time apart. When an infant would see their caregiver again, some would rush over with excitement, be comforted, and then return to playing. Some would rush over, but remain anxious and preoccupied with the caregiver, seeming to want to make sure that the caregiver wouldn’t leave again. Others would seem not to care when the caregiver returned. They would ignore them, seeming to communicate “I don’t care that you left.”

These reactions to being apart from a caregiver—who would also be called an “attachment figure”—suggested different underlying styles of relating. Some infants seemed to be anxiously attached, worrying a lot about whether a parent would be there when they were needed. They would try to stay close, checking constantly for signs of love, approval, and availability. Other infants seemed to be avoidantly attached, disconnecting themselves from the need for care. They seemed to communicate that if the parent wasn’t always around for them, then they just wouldn’t put too much effort into caring about the parent.

Flash forward to the 1980s, and psychologists start to research how these early childhood attachment styles might be linked to how adults relate to each other. Maybe, they think, we learn “mental models” or patterns about how to relate to each other in these early close relationships that we carry forward into adulthood. Maybe, for example, someone who learns to be anxious about getting enough care as an infant carries forward some anxiety about getting enough care and attention from their boyfriend or wife.

In the last few decades, there has been tons of growth in our scientific understanding of adult attachment. This research suggests that, by and large, the kinds of attachment styles that Bowlby and Ainsworth studied in infants also exist in adults, and similar dynamics play out in adult romantic relationships. Some people are anxious about being abandoned and can be perceived as “clingy” by partners. Some people seem to reject closeness and depending on others, and can be perceived as “aloof” by partners. Some people have both these traits, and both feel deeply anxious about being abandoned but also unable to open up and depend on others. These are sometimes described as “anxious-avoidant” people because they have both the anxious and the avoidant style of relating to others.

So how does all this relate back to loneliness? Well, if people in general seem to be having a hard time connecting with each other, how might this be linked to how people relate to each other? In particular, are we having a difficult time creating strong bonds with close others in our lives—like romantic partners and best friends—because of the way we think about our relationships with them? Attachment style is (probably) the most deeply developed and best-studied way of understanding how we connect with close others. So does the literature on attachment have something to say about loneliness?

It turns out, there is an often-overlooked but insightful literature on the connection between attachment and loneliness. The short answer is that there is a link. Here are some key findings:

- Securely attached people (not anxious, not avoidant) tend to report less loneliness overall.

- Anxiously attached people tend to report more loneliness, especially in relationships with family and friends.

- Avoidantly attached people tend to report more loneliness, especially in relationships with family and romantic partners.

- Anxious-avoidant people tend to report more loneliness, especially in close friendships.

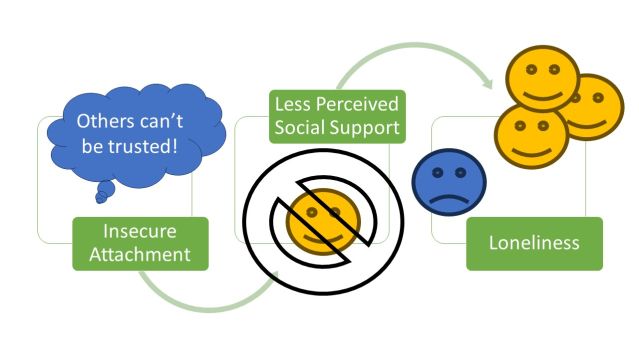

The researchers also found that perceived social support seemed to explain a big part of this link. Perceived social support is a person’s perception that someone else would be there to help them if they reached out. Here’s the way they thought it would work:

- People see others as negative or unreliable (they are not securely attached).

- That internal model of others (the insecure attachment) makes people think others won’t be willing or able to provide social support when it’s needed.

- That perception that others won’t provide social support makes people feel lonely, especially in relationships with friends and family.

Many of these correlations have a moderate to large size, suggesting that this may explain a substantial piece of the loneliness puzzle. In other words, loneliness may have a deeper root in how we tend to attach to other people. This attachment, in turn, is related to patterns of interaction learned and reinforced throughout a person’s life.

In future posts, I will keep exploring this relationship, including ideas for how to develop stronger, more secure attachments. In the meantime, you may find the book Attached by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller a good resource for starting to learn about adult attachment styles. Stay tuned.

References

Bernardon, S., Babb, K. A., Hakim-Larson, J., & Gragg, M. (2011). Loneliness, attachment, and the perception and use of social support in university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 43(1), 40.