Misophonia

Why Are Certain Sounds So Painful?

How reinterpreting the source of a negative sound can change our reaction to it.

Posted July 31, 2020

There are certain sounds nearly everyone dislikes: the sound of fingernails scratching a chalkboard, or of a fork scraping a plate, just to list a few. For many people, hearing these sounds, or even just thinking about them, elicits disgust and provokes unpleasant, almost painful sensations in different parts of the body, like the fingernails or teeth.

But why are these sounds so aversive?

Research has examined some of the auditory properties that are associated with "awful sounds." For example, a study by Reuter and Oehler (2011) found that acoustic information in the 2000 to 4000 Hz band was particularly predictive of negative reactions to natural and synthesized sounds of nails on a chalkboard. Others have theorized that there may be evolutionary advantages to being alarmed by certain sounds, like the sound of a baby crying. Certain sounds might indicate danger, and the brain may be hard-wired to respond to these sound waves.

But in recent research conducted at UC Santa Cruz, Dr. Pat Samermit, Jeremy Saal, and I proposed that there might be more to it than sound waves alone: We proposed that some sounds are aversive, in part, because of the negative mental images the sounds conjure in the listener.

Multisensory integration

Cognitive psychologists have known for decades that the senses are not independent, and in particular, auditory and visual processing are tightly linked. This can be seen in demonstrations like the "stream-bounce" illusion discovered by Robert Sekuler in 1997. Here, the presence or absence of a beep determined whether participants interpreted two balls as crossing paths (when no beep was present) or bouncing off each other (when a beep was present).

Conversely, visual events can alter what we hear. In the classic "McGurk effect" (discovered by McGurk and MacDonald in 1976), one hears the audio of a speaker saying "Ba-Ba", synchronized with a video of the speaker mouthing "Ga-Ga." The resulting perception is a bizarre morph of the two sounds; people often report hearing "Da-Da" or "Ga-Da," but almost never the original "Ba-Ba"; that is, if they are looking at the video. If they look away from the video, the original “Ba-Ba” can be heard again — try it for yourself!

A McGurk-like effect for unpleasant sounds?

In our paper published in Multisensory Research, my colleagues and I asked whether a similar "McGurk-like" effect could exist for aversive sounds. Specifically, we asked whether awful sounds, such as nails scratching a chalkboard, might sound less awful if they are synchronized with videos that depict plausible, and less aversive, alternative sources of the sounds.

For example, would the sound of nails scratching a chalkboard feel less awful if it were interpreted as a person tearing a sheet of paper? Or, would the sound of a fork scraping glass be more tolerable if it were interpreted as a bird chirping?

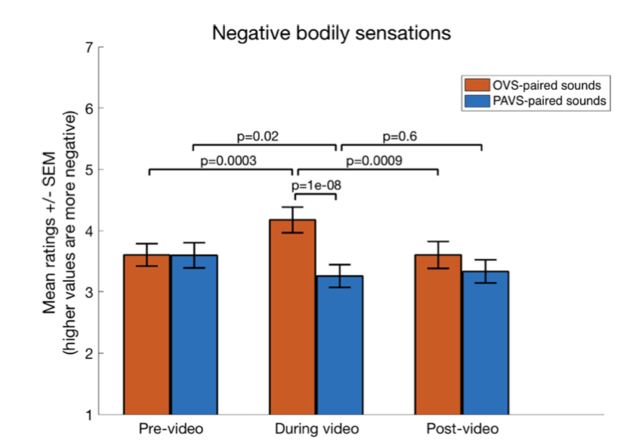

To test this question, we generated eight pairs of audio-visual stimuli that included fingernails scratching a chalkboard, metal scraping glass, a person cracking their knuckles, etc. We synchronized each awful sound with a plausible alternative source that provided a more positive interpretation (e.g. tearing paper, a bird chirping, or tapping a pen on a wooden table). Participants watched both types of videos and rated the sounds on scales of pleasantness/unpleasantness, comfort/discomfort, and on the extent to which the sounds elicited bodily sensations.

Our results showed that the concurrent presentation of positive alternative video sources (PAVS) had a big effect on participants’ reactions compared to watching the original (OVS) videos. Ratings of unpleasantness and bodily sensations were markedly lower when awful sounds were paired with less-awful alternative videos.

These findings strongly suggest that "awful sounds" are awful not only as a function of their sound wave properties. They are also awful in part because of the mental images we associate with those sounds. For example, the sound of nails on chalkboard might conjure the visual of scratching a chalkboard and an associated sensation of pain in one’s fingernails. However, if a synchronized alternative source is visually presented to the listener, at least that component of the negative experience can be averted.

Cross-sensory remapping

Our research thus has implications for how people might deal with unpleasant sounds in their environment. Rather than trying to ignore it or tune out a distressing sound (which can be difficult and even counterproductive), try reimagining the sound as coming from a different source; something plausible but more pleasant than the original source.

In ongoing work, we are examining whether this type of cross-sensory remapping can be helpful in the treatment of Misophonia, a condition where individuals experience debilitating physical and emotional reactions to certain common trigger sounds, like chewing, sniffing, or repetitive tapping. This research could point to potential therapies for Misophonia based on cross-sensory remapping and suggest a broader understanding of the condition as involving multisensory interactions.

References

Samermit, P., Saal, J., & Davidenko, N. (2019). Cross-sensory Stimuli Modulate Reactions to Aversive Sounds. Multisensory Research, 1-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/22134808-20191344.

McGurk, H., & MacDonald, J. (1976). Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature, 264(5588), 746-748.

Reuter, C., & Oehler, M. (2011). Psychoacoustics of chalkboard squeaking. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (impact factor: 1.52), 130(4), 2545.

Sekuler, R. (1997). Sound alters visual motion perception. Nature, 385(6614), 308.