Trauma

What Does It Take to Transform Trauma Into Art?

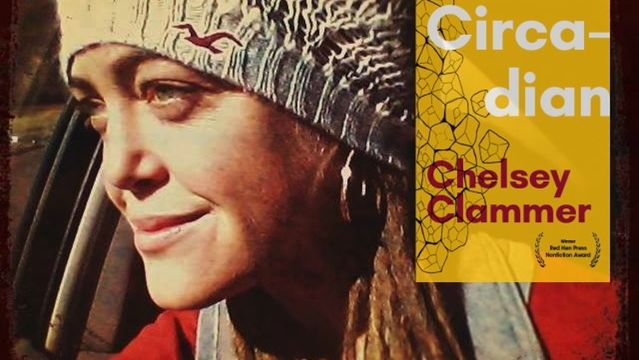

Chelsey Clammer's award-winning essay collection maps the non-linear.

Posted December 4, 2017

Winner of the Ren Hen Press nonfiction award, Chelsey Clammer's new essay collection, Circadian, merges genres as it illuminates the effects of alcoholism, PTSD, love, and mutual aid on one woman's biography-in-progress.

Living with "a slew of mental illnesses," Chelsey has developed a writing style that moves with rather than against her own neurodivergent thought patterns. The result is a dazzling—and radical—acceptance of the different ways each of us experience the world.

The author of a previous collection of essays, BodyHome, Chelsey is also the essays editor for The Nervous Breakdown.

Ariel Gore: Circadian is the best essay collection I’ve read in a long time, can you talk a bit about your writing process—the way form meets function? You use a number of experimental techniques and brilliantly evoke what it’s like to be haunted by memories and experiences. So I wonder: Do you start with form—"I’m going to write an alphabet essay" or do you start with what haunts you? Or do the form and content come to your brain together?

Chelsey Clammer: Thanks for the kind words about the collection! I started these essays in 2013 when I began my MFA program at Rainier Writing Workshop. Circadian was actually my creative thesis for that program. I wrote all the essays in two years, with the exception of “Re: Collection.” That essay was one that Red Hen Press asked for me to write to give the collection a more complete feel to it. As is true for all of my writing, when I started these essays I didn’t quite know what I had in mind for them. I just had an idea and then I started writing to see where the concept would go and what form it would find.

The only essay in the book that I started with form rather than story idea was “Outline for Change.”

I knew I wanted to write an outline essay, but didn’t quite know what its purpose would be. As I started writing, I soon realized that I was trying to bring some order to the chaos I felt while growing up with an alcoholic father.

For all of the other essays, though, the form started to emerge as I wrote them. One thing to know is that my brain doesn’t think in a linear way. I’ve tried to do that before—write chronologically from beginning to end—and each time I do it, I end up boring myself and skimming over details. So, for my writing, I have to follow the way my brain thinks—which is in flashes and concepts and ideas that might not usually speak to one another, but somehow start to make connections in my brain—such as using the mathematics of packing up a house and moving to explore more about how alcoholism can affect a family.

Also, when we experience something traumatic, our brains remember it not in a linear trajectory, but through different flashes of moments. For me, that is how I have to write about those experiences. No other way makes sense.

I feel like the essays found their form as I figured out what I was saying. Then, once I found that form, I was able to tailor my writing towards making larger connections. I kept getting new ideas and further explored what the form had to say about the story, and vice versa. Writing is an act of observation and movement—you observe, then you write, then you observe the movements that the writing makes, and then you write more.

Ariel Gore: The idea of a connection between madness and genius is loaded—and for good reasons—but there’s often such a manic-genius energy to your writing and I wonder how you feel about that loaded connection.

Chelsey Clammer: When people ask me what type of stuff I write, I usually say, “Weird shit.” In my head, I feel like you have to be a little crazy to come up with something that’s a little weird. I have bipolar disorder and I think my experience of it, as well as that of alcoholism and having PTSD, taught me that the narratives of our lives shift as our emotional perspectives on them also shift. In other words, because I’ve experienced mania, I know how to write in that sort of way (long sentences with a ton of words and barely any commas and there must be some super-quirky wording). Depression has taught me how the world slows down, and PTSD has proved to me that our brains think in flashes. I think what’s interesting about all of this is that some of these essays took months to write and I had to do a TON of revisions to get that “manic-genius” energy onto the page. It didn’t just sprout out of me—I had to revise my way there. This is where I think personal experience influences the ways we write. I’ve had all of these experiences and I know how I felt during and after them, so my job as a writer is to create the tone and energy that I felt during those moments and then shape them into something cohesive-ish on the page. This is where craft and technique come in.

Ariel Gore: That's so interesting to me—and something I can relate to as a writer. It takes a tremendous amount of slow work to capture the energy of mania—

Annie Dillard, I think, used to talk about not leaving the price tag on a piece of writing, which I interpreted as allowing the piece to appear to have sprung fully-formed from one's Zeus-head. You achieve that in these essays. I guess that’s where the genius comes in—in being able to sit down and do the slow and hard work of translating a fleeting mental state.

Chelsey Clammer: All of that said, though, I wrote “Lying in the Lyric” in one rush of pen to page. It just came out of me. The story itself had been building up in me for a few months, but each time I tried to address the issue in my writing, it wasn’t feeling like how I wanted it to feel. Then, that first line came to me: “I know I can make this all poetic and shit…” and then the essay just soared. What’s interesting is that in “Lying in the Lyric” I discuss how we try to bring our pain into a space of poetics by using beautiful language to explore it. Well, that technique wasn’t working for me. Writing in a pretty way about something super-ugly just wasn’t quite clicking. So I started to write about my process of trying to write beautifully about bulimia. Once I allowed myself to look at why I was having a hard time writing that essay, my brain just latched onto that idea and couldn’t let go of it. I revised the essay a few times right after I wrote it, then submitted it for publication that day. It was accepted a few hours later and published two days after that. So aside from that unique experience, the energy of each piece is crafted to feel kind of crazy. The energy and tone match the subject matter, and I think that any writing that attempts this is amazing.

Ariel Gore: You write a lot about trauma. Your writing is healing for the reader. There has been recent research showing that writing about trauma can be incredibly healing for the writer, too. But of course there is the concern that in writing, we'll re-traumatize ourselves.

Writing isn't therapy, but what is it? What is it for you in relationship to traumatic experiences?

Chelsey Clammer: First, there’s the purge. It’s that initial stage of putting pen to page and just getting everything out of me. That, I think, is the therapeutic part, and that fact is exactly why I have to write everything by hand first. That whole feeling a connection thing. Sometimes purging those words about trauma can be triggering. The essay “Hands” that’s in my first book, BodyHome, is about the night that I was sexually assaulted. The assault was in 2008 and I wrote the rough draft of that essay in 2011. Each time I sat down to write more of it or to revise it, I had to have someone else in the room with me. Same thing with the essay in Circadian called “A Striking Resemblance.” There are some moments in our lives that are just hard to face, so being able to have someone in the room with them as you face these memories can help so much.

For my other essays, after that therapeutic purge, working with them becomes a sort of art and science for me. I’m focusing on the sound of each word, on the flow of each image, on how one sentence moves into the next. The meaning of those words are still present in my mind and I still focus on content, but for me revision is the place where I get to heal from trauma. As in, here’s something terrible that I experienced, here’s me not silencing myself about it, and now here’s me working with it and shaping the trauma into how I want it to be. I feel like each word about trauma that I write and revise is, in a way, an act of empowerment.

Ariel Gore: In the essay "Mother Tongue," you talk about a Lexical-Gustatory Synesthesia diagnosis—basically being able to taste your words—and you use the well-placed line, “How jealous are you?” Of course those of us who struggle with mental illnesses struggle with them, but I like that you’re not afraid to talk about some jealousy-inducing perks to not experiencing the world in a neuro-typical way. Do you ever struggle with how real to be when you’re writing about lived experiences that include experiences that are also diagnostic criteria?

Chelsey Clammer: I don’t ever struggle with this because I tend not to care about revealing too much of myself on the page. I have a slew of mental illnesses, and I don’t take any of them personally. They are who I am in the same way that having dreadlocks and white skin is who I am.

In fact, I feel like writing about these subjects is, in a way, a type of advocacy. I’m giving my experiences a voice and allowing myself to not worry about what other people think about me. I write about these subjects because if I’m going to write a personal story, why hold back any? What else are we to do with these experiences but find meaning in them? And that’s why I write—to understand my own life and to encourage other people to give their tough experiences a voice.

Ariel Gore: Before my mother died she asked me if memoir writing was a way to pay tribute or a way to express anger, and I thought that was a good question. Your father’s death plays a huge part in the narratives in Circadian, and I’m assuming your mother is still alive. Whether our parents are living or dead, do you ever find a conflict between being a daughter and being a writer? Do you find the opposite of a conflict?

Chelsea Clammer: My father died in 2004, and I’ve always said that it’s because of him and his death that I have stuff to write about. Which is true. I don’t know if I would have been able to write some of these essays about him if he were still alive. But, had he not died 13 years ago, maybe our relationship would be more like what my relationship with my mother is in terms of my writing—encouraging, caring, and supportive. My mother is my first reader for everything. EVERYTHING. Even if it’s just a short bit I wrote that I think is at least semi-interesting, I’ll email it to her right away. Even if there’s sex in it. Even if there’s not-so-nice words about people she knows in it. Even if it’s about her. Even it’s about a topic that doesn’t interest her. Even if the details are probably wrong (which she’ll point out as needed). My mother reads everything. This isn’t about approval or anything, but about the ways I share my life and my writing with my mom. I feel like our relationship has become stronger because of my writing. Through essays, we’ve been able to face the different aspects of our shared past together. Each essay she reads gives her that much more insight into who I am as a person, and each time she responds to something I wrote I get that much more of a deeper sense of our connection.

Proof of how awesome my mother is: my first reading for Circadian was in New York City a few weeks before the book was to be released. I had only given a handful of readings in my life, and most of those were at coffee shops or bookstores that I worked at. So here was this NYC trip—my first experience that I knew would make me feel like a “real” writer. The day before the trip, though, I got really sad because I wouldn’t have anyone to celebrate the experience with. When I told this to my mom, within a few hours she bought plane tickets to come and join me the next day! I told her she could stay with me at the aribnb place since I had already reserved it. When we got there we found out that my “room” was really a cot-sized mattress on a makeshift loft the dude had put up above his kitchen. My mom and I totally slept in that bed together. We didn’t exactly cuddle, but there definitely wasn’t a lot of room up there.

So, that’s us.