Happiness

Does Witchcraft Hold the Secret to Happiness?

Claiming the witch archetype is a means of self-empowerment.

Posted October 15, 2019 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

On a rainy fall morning, I went to see my neighbor Erika Wanenmacher, Santa Fe’s famous “Ditch Witch,” in her industrial studio down the street from my house. She wanted to show me a giant glass and metal spider sculpture in which she’d included my art-spell image that was widely invoked during the Brett Kavanaugh hearings: A round, flower-eyed icon that reads, “Commence Psychic Hex on Liars.”

I shared my latest personal and political woes with Erika, and she gave me some of her homemade magical incense formulated for specific intentions: Gratitude, Lighten the Load, Protection, and “I Can Do This!”

On my altar back home, I piled the incense on charcoal and lit it, focusing on reclaiming the power that patriarchal culture has leeched from me.

This is a casual, neighborhood magic. It keeps up morale.

Witchcraft has long been taboo, and witchy traditions have been kept secret largely for the safety of its practitioners, but feminist witches are coming out. Even The New York Times last week proclaimed, “Witches are Having Their Hour.”

I was raised by my stepfather, an excommunicated Catholic priest who supported the Black Panther Party, ran the local chapter of Amnesty International, used his Ouija board to speak with spirits, and could move physical objects with his mind, and by my mother, a short-tempered feminist named Eve who got called “witch” for seducing him. Still, I didn’t formally initiate myself until I was a 21-year-old single mom surviving on welfare and student loans. The patriarchy had me by the throat in the form of misogynist family court judges, food-stamp-cutting governors, and national politicians always eager to dehumanize poor women to feed their own greed for power. I’d been talking to owls since before I could talk to people, but now I needed a more structured approach: I would magically defend myself from the patriarchy and, once I’d recovered my strength, go on the offensive. Hexing the patriarchy wouldn’t be about hurting anybody, but rather about protecting myself and other marginalized people from The Man’s abusive impulses.

Wicca, a modern pagan religion and spiritual movement some witches adhere to, is now the fastest-growing religion in the US according to recent studies. And witchcraft—whether Wiccan-identified or not—is expanding exponentially.

Because of a sense of political emergency fueled by misogynist lawmakers and a sense of security patched together by generations of feminists, more and more people of all genders are identifying as adherents to magical spiritual traditions from Wicca to Voudoun to Brujaria to Modern Spiritualism. But magic is nothing new. All pre-capitalist societies believed in magic. All indigenous people had magical folk traditions. And all of our ancestors were indigenous to somewhere. So, if your great-grandmother wasn’t a witch herself, her great-grandmother likely was. In that sense, we’re all the descendants of a witch they never managed to burn—or one who procreated first.

Inga Aaron, a priestess of Yemaya and contributor to my magical primer, Hexing the Patriarchy: 26 Potions, Spells, and Magical Elixirs to Embolden the Resistance, explained her path to rediscovering the African Diaspora Religion, or ADR, she now practices: “I was raised completely without religion, although I did believe in ‘something larger than myself.’ As an adult, I found new age practices, but they weren’t the right fit for me. I’m grateful, though, that they led me to an African Diaspora Religion. ADRs managed to survive the Transatlantic slave trade albeit under duress. Mostly Catholic slaveholders throughout the Caribbean forced slaves to abandon their practices and believe only in the Bible. Sadly, the continent of Africa suffered the same indoctrination with only 20 percent of its inhabitants now practicing African Traditional Religions. ADRs survived via the formidable will of my ancestors. I felt a connection to the practices African peoples did before slavery. The connection to the earth in all of her manifestations called me. I answered the call.”

From a psychological perspective, claiming the witch archetype is a means of self-empowerment. It’s about resisting the false dichotomy of “good girls” and “bad girls.” Complicated women don’t want to choose. Today’s feminist witches aren’t “bad” or “good.” We reject talk about “white magic” versus “black magic” as both a false binary and as racist.

Moe Bowstern, another contributor to Hexing the Patriarchy, defines the term “witch” broadly in the introduction to her forthcoming zine, When a Witch, saying, “I am a witch, which is to say, I am a human being who believes that I am alive, the earth is alive and I am connected to the earth; in that connection I have the power to influence and be influenced by the earth, the stars and all of us who live in between.”

In the piece “How to Write a Spell Against White Supremacy,” Neesha Powell explains the difference between religion and magic this way: “Most religions require worship of a patriarchal figure who punishes you for doing wrong, while magic allows us to harness our power within . . . I define magic as creating desired change by performing rituals for those who guide and protect you, whether they be ancestors, goddesses or a natural wonder.”

In collecting the spells for Hexing the Patriarchy, I wanted to include practices from all kinds of magical traditions—and not all of those are considered traditionally religious or spiritual.

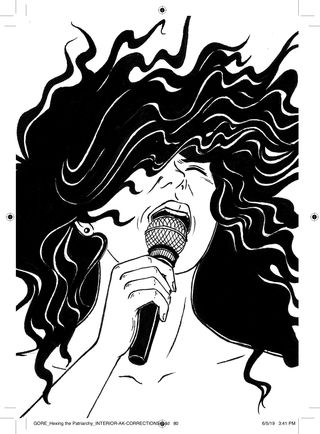

Michelle Gonzales, former drummer for Spitboy, current guitarist for Kamala and the Karnivores, and author of The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band, for example, offered a “Grrr Hex” in the long tradition of music as magic.

“When I first wrote Grrr Hex,” Gonzales explains, “I hadn’t quite understood intellectually how closely related a spell is to a song. Song lyrics, like spells, cut to the bone of a feeling or idea, and turns of a phrase are their magic. The space you inhabit when you perform a song is magic too. In many ways, I live for that feeling of being under the spell of a good song, especially a song that incites socio-political action.”

Many magical traditions teach that whatever we put out into the world comes back at us three-fold, so we’re careful not to put anything out there that we wouldn’t want triple-boomeranged back in our face. On the other hand, this is true: Oppressed people have often survived by hexing their tormentors.

Anne-Maria Makhulu, an assistant professor of cultural anthropology at Duke University, has noted that belief in magic fills a deep human desire for equality. "When people say they believe in magical forces, they believe in the magic that can make the world equal and just in circumstances where it’s not," Makhulu told Science Daily. For some, "witchcraft is about recuperating what is ethical, just and moral."

In pursuit of that recuperation, some witches rejoin the religions of their ancestors. Some witches talk to the dead. Some track the rhythms of nature. Some read Tarot cards. Some cast spells to protect the marginalized and bind the powerful. Some start bands and sing their spells to music. All of us endeavor to harness our own power, and trust our own intuition and spiritual authority over anything organized religion or government is going to tell us is real.

Positive psychology correlates happiness with resilience, and with having some sense of control over our circumstances. Witchcraft offers both. Contemporary witchcraft is about asserting our own agency whenever that agency is threatened—and it’s about building the psychic strength to fight back against abuse and injustice.

There’s a direct line from feminism to witchcraft. Always has been.

As Pam Grossman, author of Waking the Witch, recently told The New York Times, “The witch is a feminine archetype who has authority over herself. She doesn’t get power in relation to other people. She has power on her own terms. And because of that, she is, I believe, the ultimate feminist icon.”

Melanie Oma Hexen, the Iowan grandmother and midwife famous for publicly hexing Stanford rapist Brock Turner, contributed instructions on making a personal “servitor”—or a magical being that can then be sent into courtrooms or houses of representatives to influence outcomes—to my spell collection. Hexen is a believer, but she made clear that it doesn’t matter whether we think of these servitors as real entities or as psychological exercises. “Either way,” she promised, “it will work.”

And it’s true. When bad things happen—an environmental illness diagnosis in my family or a wildfire in my community or election theft in my country—part of my grief is the sense there’s nothing I can do about it all. Witchcraft has taught me that there’s always something I can do.

I go see a neighbor.

We collaborate on political art.

We gather our strength.

And we commence all manner of psychic resistance.

The global mess we’re in might be more complicated than abracadabra! can fix in an instant, but there’s always something we can do.

That authority brings with it a fierce sense of purpose—and joy.

My latest book, Hexing the Patriarchy: 26 Potions, Spells, and Magical Elixirs to Embolden the Resistance, is out today from Seal Press.