Circadian Rhythm

Pain’s Circadian Clock

Understanding when we hurt the most and why.

Updated June 25, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Time of day is a commonly overlooked factor in pain.

- Seven types of pain and when they peak throughout the day can help us adjust treatments.

- All flare-ups aren't caused by something we did "wrong" but follow a pattern and will ease.

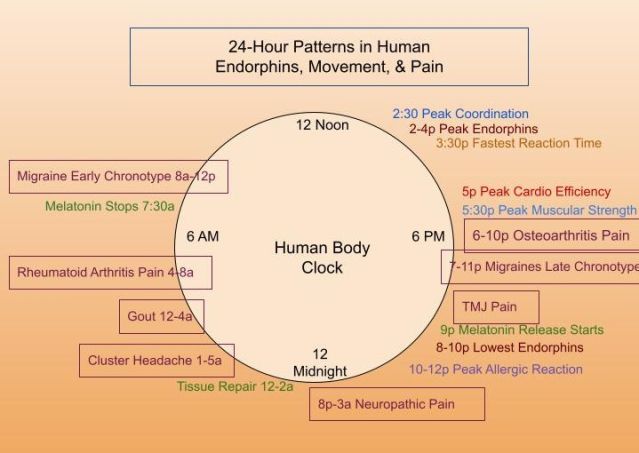

Many things impact how we each experience pain. Commonly overlooked influences on pain are the 24-hour fluctuations of daily biology naturally woven into each day. Timing is everything to each cell's clock. Hormones and neurotransmitters ebb and flow throughout the day, predicting and delivering resources to meet our needs and feel our best.

The fast-growing research on circadian neuroscience is uncovering fascinating patterns in our biology that are woven into every moment of every day. Below are seven types of pain and their peak times of when they hurt the most. The seven types of pain mapped here include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, neuropathic pain, migraines, cluster headaches, gout, and temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJ). Please note these are averages, which means they do not fit everyone, but they do shed light on the arc that certain types of pain take throughout the day, month, or year.

7 Types of Pain and When They Tend to Peak

1. Osteoarthritis is a degenerative disease; its pain peak average is at the end of the day. The intrinsic rhythm of cartilage repair may be related to melatonin and other neurochemicals released at night.

2. Rheumatoid arthritis, understood to be an autoimmune response, has a well-known pattern of peaking in the morning along with hormone fluctuations and inflammatory cytokines.

3. Neuropathic pain peaks in the late evening and early morning hours, possibly related to the timed release of substance P, a pain-modulating neurotransmitter.

4. Migraine flares depend on your chronotype—whether you tend to wake up early and function best before noon or sleep late and feel best in the evening. Morning chronotypes have more migraines in the morning, while late chronotypes have more migraines in the evening and night. People with migraines are more likely to be morning larks.

Migraines also have a monthly rhythm that cycles with menstruation and a decrease in estrogen. Their annual rhythms peak in spring and fall.

5. Cluster headaches have a very precise nighttime recurrence and also repeat at the same time of year. The most common time is 2 a.m. (in around 82 percent of people); spring and fall are the most common seasons. Cluster headaches appear to be strongly interconnected to the trigeminovascular pain system (cranial nerves and blood vessels), the autonomic system, and the hypothalamus.

6. Gout, a buildup of uric acid crystals in the toe, ankle, knee, and wrist joints, peaks around 3-4 a.m.

7. Temporomandibular joint pain is higher for about 80 percent of people late in the day into the evening, leaving roughly 20 percent experiencing peak pain in the morning. This may be related to the growth and repair of cartilage in addition to behavioral patterns and stress.

4 Reasons This Matters

Understanding the types of pain and when they peak can make a big difference in several ways.

1. It may improve treatments. Over 100 medications have been found to have circadian physiology (timing) that significantly impacts the effectiveness and also the severity of side effects. Timing medication to maximize positive effects and minimize unwanted effects is called chronopharmacology, a type of chronotherapy. One example of this is rheumatoid arthritis: glucocorticoids taken at night instead of in the morning have been shown to reduce pain the most.

2. It is validating. Pain that makes a predictable pattern gives some sense of rhyme and reason. It could also prevent a misattribution to something the sufferer did "wrong" to cause the flare.

3. It helps us plan ahead. Noticing a pattern of pain may also help us prepare for the peaks and valleys. Activities and rest can be planned with the anticipated surge in mind.

4. Trust that the pain will ease. Last but not least, observing these biological ebbs and flows can guide each of us toward more patience during a flare and encourage calm abiding, trusting that the tide will recede. The uncertainty of when the pain will ease can, at times, be one of the most challenging parts of pain management.

Research in the area of circadian neuroscience and chronotherapies is emerging quickly in all key areas of health, offering insights into how to function and feel our best. Improvements in pain have already been found with light therapy and sleep improvement. Even small efforts to strengthen circadian physiology improve mental and physical health.

References

Warfield, A. E., Prather, J. F., & Todd, W. D. (2021). Systems and Circuits Linking Chronic Pain and Circadian Rhythms. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 705173. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.705173

Burish, M. J., Chen, Z., & Yoo, S. H. (2019). Emerging relevance of circadian rhythms in headaches and neuropathic pain. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England), 225(1), e13161. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.13161

Smolensky, M. H., Portaluppi, F., Manfredini, R., Hermida, R. C., Tiseo, R., Sackett-Lundeen, L. L., & Haus, E. L. (2015). Diurnal and twenty-four hour patterning of human diseases: acute and chronic common and uncommon medical conditions. Sleep medicine reviews, 21, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.005

van Grootel, R. J., van der Glas, H. W., Buchner, R., de Leeuw, J. R., & Passchier, J. (2005). Patterns of pain variation related to myogenous temporomandibular disorders. The Clinical journal of pain, 21(2), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200503000-00007

Levi, F., Le Louarn, C., & Reinberg, A. (1985). Timing optimizes sustained-release indomethacin treatment of osteoarthritis. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, 37(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.1985.15

Cutolo, M., & Masi, A. T. (2005). Circadian rhythms and arthritis. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America, 31(1), 115–x. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2004.09.005

Leichtfried V., Matteucci Gothe R., Kantner-Rumplmair W., Mair-Raggautz M., Bartenbach C., Guggenbichler H., et al. (2014). Short-term effects of bright light therapy in adults with chronic nonspecific back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 15 2003–2012. 10.1111/pme.12503