Sleep

How to Train Your Gut Clock

The timing of when you eat affects your health more than you might think.

Updated June 25, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Digestion has optimal timing that when disrupted, can lead to weight gain, worse mood, and metabolic diseases.

- Chrono-nutrition studies the science of when we eat and the remarkable impact it has on health.

- The intake of food can be timed to lose weight, prevent disease, and improve energy, mood, and focus.

- These 5 rules can lead to significant health benefits—even if you don’t want to change what you eat.

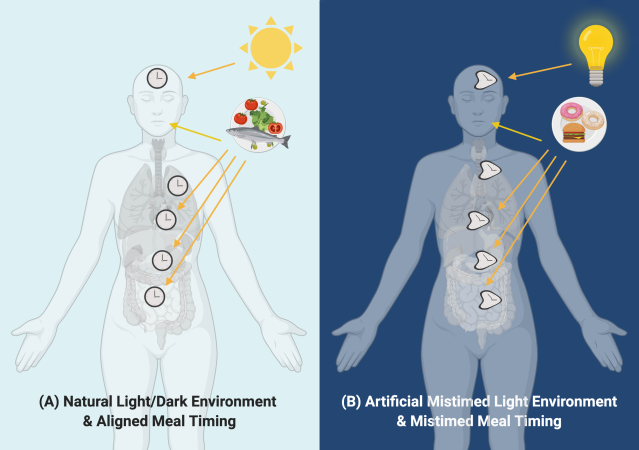

Metabolic rhythms of our digestive system are intricately linked to our circadian rhythms of waking and sleeping. What time of day we eat affects what our brain and body anticipate (through the processes of allostasis) and this has everything to do with how we metabolize sugars, how our bodies store fat, and is even related to things like regulating body temperature. Our circadian clock molecules are more sensitive to when we eat than we ever knew before. The risks of uncoupling or desynchronizing these body clocks are numerous (Flanagan, et al, 2021).

Chrono-nutrition is the emerging field of science that explores the intricate timing of eating patterns and how they coordinate with metabolic, circadian, other biological rhythms, and how these all function to impact health. Our habits around what we eat, but also particularly when, affect the ebb and flow of our nutrition-related hormones and neurochemicals. When we eat can disrupt the functioning of our entire 24-hour clock, leading to fatigue, hunger and cravings, poor mood, and lack of focus. Or the timing of food intake can be an anchor that supports the flow of other biological rhythms, so we are focused, experience improved mood and energy, and even prevent metabolic diseases.

Chrono-nutrition behaviors include:

- Frequency: how often we eat.

- Regularity: how regularly we eat.

- Duration: the span of hours we consume calories.

- When: time of day we eat.

What Happens When We Eat at the Wrong Time of Day

Our sleep-wake cycle has a central clock in the brain (the SCN) that coordinates with the other peripheral clocks located in the gut, pancreas, and liver, along with several digestive hormones. Gut bacteria outnumber our own cells by over 40 percent and set their timing to match our gut cell clocks. Ghrelin, leptin, and insulin all shift their timing of release based on when we eat. Appetite gets distorted when these hormones that help us feel full are out of synch, which also impacts fat storage via clocks in our adipose tissue.

The vast majority of us have better glucose tolerance earlier in the day compared to evening and working against this system can dis-regulate blood sugar. Poor regulation of blood sugar can develop into diabetes, or high blood pressure that can develop into hypertension and excess body fat that contributes to many, if not most diseases, including heart disease. See the image below for what happens when we eat at unnatural times for our 24-hour biological clocks (Flanagan et al, 2021).

Habits that uncouple and stress these body clocks include:

- Excess food in the evening, when we need calories the least.

- Skipping meals or erratic meals.

- Eating too often, more than four times per day.

- Eating too much overall.

- Eating sugar and processed foods.

These behaviors tax our body’s attempts to deliver what we need at the right time. If it was as simple as homeostasis (balanced regulation) we would simply eat the calories we need. But our body prepares for and tries to anticipate when it may not have regular food (from skipping meals), when it may have too much food, high sugar intake, and when we are stressed. Under variable circumstances, our system struggles to manage yet tries to adapt the best it can.

5 Rules to (En)Train Our Food Clocks

Research in chrono-nutrition shows that people who eat their biggest meal at breakfast or lunch instead of dinner have lower BMI (body mass index). This brings us to the first rule of thumb.

Rule #1: Eat more calories in the morning, or at least by 3 p.m. If your first meal isn’t your biggest meal, have it be your second meal. Your last meal is the best as the smallest.

But, what can you do if you are not an early eater and your stomach is not ready yet for food? Start with one bite of something and gradually increase the amount of calories earlier in the day and your physiology will shift over time to match your behavior. Slowly shift the first bite of food just a few minutes earlier each day.

Eating sends the message to be awake, which is why morning calories are best. However, evening eating may disrupt natural melatonin release that begins around 9 p.m. Calories around this time are associated with increased fat storage and worse glucose regulation. Therefore,

Rule #2: Don’t eat in the evening.

Avoid eating near the time melatonin would optimally release—approximately 9 p.m. Stop all calories two to three hours before this. This occurs naturally if we eat within a 12-hour window, such as 7 a.m.-7 p.m. Digestive rhythms work better over 12 hours than over a 15-hour period (i.e., 7 a.m.-10 p.m.).

The regularity of when we eat also matters. Our brain and body continually seek to anticipate what energy we will need for the day and balance that energy based on its best calculation. Insulin, for example, releases in preparation for your next expected snack or meal. It does its best to be flexible, but works better when it knows what to expect. So, here are the next two rules of thumb:

Rule #3: Eat regular meals (more or less), so the body can prepare in advance. Create a daily rhythm (habit) and,

Rule #4: Do not eat during the hours you would like to be sleeping.

Our brain and body are smart and quickly learn to wake up in anticipation of a late-night snack, no matter how healthy it is.

Also, remember, if you have any trouble sleeping or waking up feeling good, catching up on sleep over the weekend will disrupt the 24-hour clock. So,

Rule #5: Do not sleep in on your day off—no matter how tempting it is.

See the diagram below to see an optimal pattern of eating behavior and physiology over 24 hours.

.jpg?itok=J-YwFCUC)

Some of these rules sound like no fun, especially no night eating and no sleeping in. But the payoff is that once your biological rhythms have a chance to align, the reward is better sleep and mood, fewer food cravings, preventing metabolic diseases, and feeling better more often.

References

Flanagan, A., Bechtold, D. A., Pot, G. K., & Johnston, J. D. (2021). Chrono-nutrition: From molecular and neuronal mechanisms to human epidemiology and timed feeding patterns. Journal of neurochemistry, 157(1), 53–72.