Politics

A Humanist Take on the Crisis in the Middle East

Darwin's insights can shed light on today's most difficult issues.

Updated June 6, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Humanism has roots in natural selection, which focuses on the shared heritage of all life forms.

- The converse of humanism is seen in ingroup/outgroup bias, which underlies the worst of the human experience.

- If people don't take a humanist approach to the problems of the Middle East, suffering will continue.

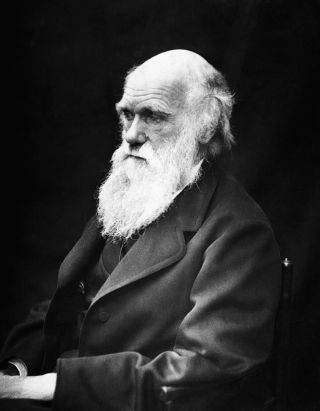

Each year, humanist organizations around the world celebrate the birthday of Charles R. Darwin, whose ideas on the origins of life changed our understanding of the world—and our place in it—permanently. For nearly a decade, members of my research team, the New Paltz Evolutionary Psychology Lab, and I have given presentations in honor of Darwin Day (as this celebration is now called) for our local humanist organization: The Hudson Valley Humanists.

There are two critical reasons that Darwin’s ideological legacy sits so centrally in the humanist ethos. First, in spite of being a deeply religious Christian, Darwin's ideas ultimately came to underscore secularism, a broad term for any set of ethical and moral principles that are not connected with any particular religious ideology. The idea that humans—along with dandelions, mosquitoes, tulip trees, groundhogs, goldfinches, and emperor penguins—along with all other forms of life—came about by natural selection (see Darwin, 1859), focuses on natural/physical processes as shaping all life forms that have ever existed. This concept, which, as Darwin himself put it, suggests that "... there is grandeur in this view of life," is incongruous with origin explanations from any particular religious sect. This scientifically grounded view of the world is, the basis of secularism and of its sister ideology, secular humanism.

A second critical way that Darwinism paved the way for humanism is a corollary of his basic ideas on human life being rooted in natural selection. Darwin was a humanist at heart. In fact, there is a plentitude of data speaking to the fact that Darwin was not only an unabashed abolitionist, but that, in many ways, he was more of an abolitionist than was Abraham Lincoln (see Desmond and Moore's 2014 book, Darwin's Sacred Cause). While on his famous voyage around the world in the early 1800s, Darwin was quick to point out that people from places that were very different from his home were necessarily humans just like himself and his shipmates (in spite of others at the time disagreeing with him; see Eldredge, 2005).

In each of the aforementioned ways, Darwin's ideas paved the way for modern humanism.

Humanism and Ingroup/Outgroup Behavior

The humanist ideology has paved the way for such important modern institutions as Amnesty International, the United Nations, Doctors without Borders, and others. While not everyone identifies as a humanist today, it is clear that the humanist initiatives that have followed Darwin's footsteps are important in the modern world.

Yet, humanism is not without its obstacles. One of the strongest biases surrounding our evolved social psychology is found in the ingroup/outgroup bias (see Billig & Tajfel, 1973). This bias, which, in many ways, underlies the most treacherous elements of the human experience, basically is a strong tendency for people to over-favor members of groups that they define as "their" groups compared with those who they define as in some "other" group. In essence, this bias can be seen as an "us versus them" mentality, which has strong roots in our evolutionary history (see Wilson, 2019).

Ingroup/outgroup thinking is responsible for so many atrocities across history. Consider, for instance, the Civil War, World War II, apartheid in South Africa, and more. Unfortunately, way more.

Ingroup/outgroup thinking is the Achilles' heel of the human experience. It flies directly against all the principles of humanism.

Ingroup/Outgroup Psychology and the Conflict in the Middle East

As someone who truly and explicitly identifies as humanistic, I find myself on the lookout for ingroup/outgroup thinking and actions.

The current conflict in the Middle East has, in many ways, taken center stage in terms of what is happening in the world today. While I hardly have the education to comment on the history of the issues in a comprehensive fashion, I think that I am qualified to talk about the evolved psychology that surrounds what is happening.

A few months ago, I was in a social setting that included a scholar from Israel, who happened to share my own ethnic heritage, that is, ethnically Jewish. I partly mention this connection to show that there is more ideological variability when it comes to the Middle East within members of "the same group" than one might think is the case.

This scholar, a current college student, and I were having a nice conversation about the details of having a career in the sciences. The scholar was a very bright and successful individual and I was deeply impressed with him.

At some point, the student asked him a question that changed the conversation completely: "What do you think of what's happening in Israel now?" Note that this conversation took place after the Hamas attacks of October 2023.

The scholar changed his tone dramatically and immediately. He became emotional—upset and angry at the same time. But what concerned me most was how quickly he burst into "us and them" language. He was saying things along the lines of how "we" (the Israelis) are so much better than "them" (the Palestinians) and he took a militant and polarizing angle on the whole thing. After speaking emotionally about the situation for a few solid minutes, he stopped himself. His breathing was heavy. And he said that he was done talking about that issue. He looked deflated.

As a Darwinian-inspired humanist, I have to say that I was disappointed. I don't fully blame him; his experiences are what they are. Yet I found much of his rhetoric concerning. If there is one rule of history that evolutionary psychology can shed light on, it is this: Once "us and them" thinking gets involved in social conflicts, those conflicts are only going to escalate (see Smith, 2008). And that is exactly what is happening in the world today.

To the extent that ingroup/outgroup reasoning permeates perceptions of the crisis in the Middle East, we all lose. Once people start valuing human life from one ethnic background over some other background, our shared humanity suffers.

Bottom Line

People may not realize it, but Darwin was actually a dyed-in-the-wool humanist from the outset (see Desmond & Moore, 2014; Eldredge, 2005). He even went beyond humanism, glorifying the fact that the entirety of life is inter-connected and that it all traces back to a common ancestor. As Darwin himself said, "There is grandeur in this view of life." I think it is hard to argue with this point.

The ingroup/outgroup bias pushes against the foundation of humanism, encouraging people to value those who are similar to themselves over others—often in ways that are unfair and irrational.

The conflict in the Middle East provides an opportunity for the entire world to step back and take a humanistic perspective. Sure, we can focus on this group versus that group. Or we can step back and work to develop solutions that value human life equally, regardless of ethnic or religious heritage. As Darwin pointed out nearly two centuries ago, people are people wherever they come from. And differential treatment of people due to group differences is nothing short of inhumane (see Desmond & Morris, 2014).

As we work together as a global community to address the problems that are spreading from the Middle East to all corners of the world, I suggest that people take a step back and consider a humanist approach. At the end of the day, we all have a ticket on the same ride. This fact is as true in the Middle East as it is anywhere.

References

Billig, M., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3, 27–52.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life (1st ed.). London, UK: John Murray.

Desmond, A., & Moore, (2014). Darwin’s Sacred Cause: How a Hatred of Slavery Shaped Darwin’s Views on Human Evolution. New York:: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Eldredge, N. (2005). Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life. Norton.

Krueger J, Clement RW. The truly false consensus effect: an ineradicable and egocentric bias in social perception. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994 Oct;67(4):596-610. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.596. Erratum in: J Pers Soc Psychol 1995 Apr;68(4):579. PMID: 7965607.

Smith, D. L. (2008). The Most Dangerous Animal. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Wilson, D. S. (2019). This View of Life: Completing the Darwinian Revolution. Pantheon: New York.