Punishment

Hail Caesar! When Personal Resentments Spur Political Revenge

Exploring the melding of politics and psychology.

Posted June 20, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- From Sigmund Freud to Alfred Adler, from personal libido to political life, the thrust to power fuels the thirst for revenge.

- We mask our pursuit of power and sublimate our rage, often through passive aggression and shaming.

- Without great power, comes great resentment, which propels us to seek solace and safety in the powerful.

- We channel our grievances, insecurities, and resentments, through our leader, to seek revenge and redemption, turning politics into therapy.

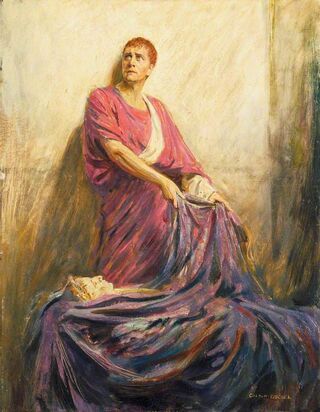

Cæsar died last night at Shakespeare in the park. While the last dagger extracted Julius’s “Et tu, Brute?” I was wondering: Why did the Roman populous love Caesar so much? What turned Caesar into a leader to live for and die for, even after his own death? And what can we learn from it about modern people’s love for their leaders?

The unkindest cut: the taste of treason

Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Julius Caesar offers clues. Having demonstrated Caesar’s mortality, Brutus, confident in his moral standing and rhetorical mastery, justified the assassination: “Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more. Had you rather Caesar were living, and die all slaves, than that Caesar were dead, to live all freemen?” His compatriots in Rome’s square inhale the orator’s dilemma and exhale consensus: better to live in liberty than under a perpetual dictator.

But the whirlwind of words soon turned. When Antony steps up, asking his “Friends, Romans, countrymen,” to lend him their ears, he slowly but surely gains their hearts and minds. His Caesar was no tyrant, but victorious and generous, and filled with love—not least for his would-be assassin:

For Brutus, as you know, was Caesar's angel:

Judge, O you gods, how dearly Caesar loved him!

This was the most unkindest cut of all;

For when the noble Caesar saw him stab,

Ingratitude…

This “unkindest cut” went through the Romans’ hearts—and mine too. Ah, the betrayal! One can almost taste the treason, feel how the benevolent leader, lovingly laboring for the people, was butchered by villains who accused him of their own deepest sins: fantasies of grandeur and ruthless ambition. Caesar needed no fantasies, he was genuinely grand; his ambition was just right—kind to his people, fierce toward their enemies. Didn’t he thrice magnanimously refuse Antony’s offer of “a kingly crown... Was this ambition?” Surely not. Yes, as Antony said, “all did love him once, not without cause,” and now, with a rush of blood, we can find a cause worth fighting for: avenging his murder. Thus begins Caesar’s civil war (49–45 BC) that killed the Roman Republic and begot the Empire.

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of – power?

What drives political vengeance? Surely not human nature. If people mostly want to liberate their lives in pursuit of personal happiness (read: pleasure) why on earth would they shed blood for others, let alone those already dead? But if we move from Sigmund Freud to Alfred Adler, from personal libido to political life, from the pleasure principle to the pursuit of power, and to the ways people overcompensate for their inferiority complex, vengeance makes more sense. On this account, the thrust to power fuels the thirst for revenge.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s stress on people’s “will to power” laid the philosophical groundwork. Tracing The Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche argued that the weak could never defeat the strong one-on-one, but they did outnumber them and so turned their inferiority to righteous resentment by forming “slave morality” that deprecates the strong as wrong. If you can’t win over them, whine about them.

Nietzsche has a point, likely in the past, and certainly in the present. If we think of power imbalance as the ultimate abomination, the weak become innately righteous, victims deserving of justice through equity. But “power imbalance” is pleonasm: power always means imbalance. Power, by definition, is the capacity to control others, which presumes power’s unequal distribution. Pursuing power to repair imbalance only affirms power’s psychological and practical potency: people want power, which is why we typically end up replacing one imbalance with another.

Can we stop wanting power? Perhaps by negating the "self" (the Buddhist Anattā) to remove human suffering (Dukkha), or, more existentially, by favoring the free pursuit of purpose (over pleasure and power), we can make ourselves anew. But for now, in our power-thirsty world, we can at least make believe, pretend we’re not really after power, at least politically.

One way to go about this charade is transposing our pursuit of power from politics to personal and professional relationships: we’ll seek domination in the small circles of family, friends, partners, and colleagues. Another way, both private and public, is passive aggression. Passivity masks our pursuit of power; rhetorical aggression sublimates our rage—we guilt-trip others to assert our moral superiority. Yet another way is shaming, often online. We mask our weaknesses by finding strength in numbers and sublimate our rage in moral outrage. Like cyber spiders, we weave a mobweb out of the world wide web, hardly noticing that we’re trapping ourselves.

Politico-therapy: When politics become therapy

Nietzsche had a point but missed a spot. The weak resent their own frailty no less than they envy the strength of others, and, being humans, we’re all frail. We never get all we want; unlike Nietzsche’s dead God, we do not have total power. And without great power, comes great frustration. In frustration, we raise a clenched fist against the universe, the system, and people all around—against the cards we’re dealt that often seem stacked against us.

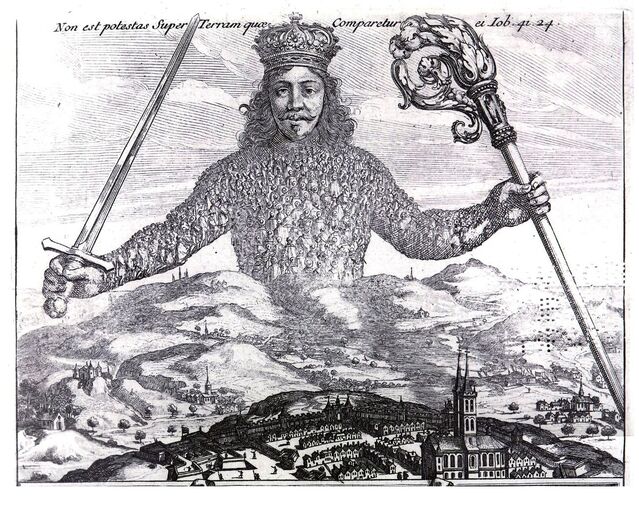

This indignation can breed a grudging solitude or the courage of true solidarity in grasping the power of the powerless. But, just as often, our resentment propels us to seek solace and safety in the powerful. The people then become plates in their protector’s cuirass, as in Thomas Hobbes’s frontispiece for his Leviathan, featuring a fearful symbiosis of diffident persons and one mighty individual.

All this seems to suggest an inherent contradiction between victimhood and might. The weak we pity or dismiss; if the former, we may lend a helping hand. The mighty we succumb to with fear or reject in courage. Presumably, once a leader seems weak, let alone a victim, we opt out, preferring the protection of the powerful.

However, this is only a partial picture. Victimhood and might can coexist, even coalesce, and when they do, something else happens: as it does poignantly in Shakespeare’s Caesar. When Antony delivers his speech over Caesar’s corpse, we catch a glimpse of the combustive and combative combination of victimhood and might. Caesar is both, at one and the same time: a victim—of his assassins—for being so mighty, and is seen as mightier still—by his subjects—after death and martyrdom.

Sensing that our strong leader has been betrayed, we not only adore him, but identify with him, for betrayal is something we all recognize. We have all been wronged. We can now channel our grievances, insecurities, and resentments, through our leader, to seek revenge and redemption. We turn politics into therapy: politico-therapy. “Hail Caesar!” we say, hoping to heal ourselves. We won’t. The tragedy of Julius Caesar is ours.