Self-Talk

Understanding the Inner Critic

This pervasive and destructive stressor contributes to psychological suffering.

Posted December 15, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Many people have an inner critic that scrutinizes and negatively evaluates their actions.

- The inner critic drives a person towards unrealistic standards, persistently demanding productivity.

- Non-compliance with the stringent standards contributes to a sense of inadequacy and worthlessness.

Every person has a side of themselves that continuously observes, monitors, and evaluates their actions. Self-criticism is an automatic, largely unconscious psychological tendency that people occasionally engage in.

When faced with failure or hardship, some people experience a milder presence of self-criticism and may ultimately respond to the situation with self-compassion. However, many others live with an unfriendly and critical inner voice, manifesting through negative thoughts, which distort how they perceive things.

In other words, they have an inner critic that passes judgment accompanied by feelings of hostility, and contempt. It drives a person towards excessive self-reliance and persistently demands productivity.

While having a critical inner voice is common, for many people, such a voice is so normal that they don’t even notice it. Instead, they frequently find themselves in a depressed or anxious mood. Self-criticism is considered to be among the most common and destructive stressors linked to different forms of psychological suffering, including depression, perfectionism, imposter syndrome, social anxiety, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and borderline disorder among others.

Self-criticism is a multifaceted phenomenon that persists and doesn’t simply fade away with time, however, it is possible to diminish it. A crucial first step in facilitating change involves people becoming aware and comprehending the origins, styles, and functions of their self-criticism.

The High Performers Paradox

Many high-achieving individuals often have a heightened level of self-criticism. Driven by high standards through their relentless self-critical voice, they push themselves to achieve excellence.

This approach proves effective to some extent, as these individuals tend to produce outstanding work. The inner critic undoubtedly wields significant power, manifesting in qualities such as perseverance, ambition, and meticulous attention to detail.

Yet from a different perspective, in the pursuit of self-imposed standards, they face continuous anxiety about their progress, fear of failure, and unhealthy comparisons with others. They may turn to self-criticism as a strategy to amplify their efforts and stand out at work, convinced that their self-improving form of self-criticism contributes to their success. However, this approach backfires when people find themselves unable to meet the expectations. When not met with success, these individuals often face profound feelings of inadequacy and worthlessness.

The Two Conflicting Sides

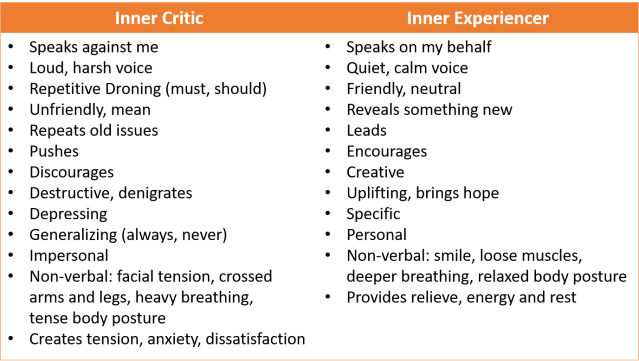

Self-criticism, as conceptualized in emotion-focused therapy, involves a self-to-self relationship where different facets of the self engage in internal conflict. In this intricate dynamic, one facet, the inner critic, assumes the responsibilities of criticism and judgment. This dominant facet impedes the experiences and healthy needs of another facet of the self, often identified as the experiencing self.

The inner critic strives to adhere to established standards and norms, while the other aspect, the experiencer, represents a more adaptive and fundamental part of the self that instinctively knows what is right and desires to follow its inclinations. The interaction between these two facets leads to tension due to the clash in their viewpoints.

The Inner Critic Processes

Reflect on the familiar scenario in which a person feels an internal compulsion to give and do for others. Even when they recognize that they are exceeding their capacity and should set boundaries, they struggle to stop.

A part of the self, the experiencing self, recognizes the discomfort in the situation, indicating a need to cease giving. When it endeavors to assert its limits, it encounters "stuckness" preventing the expression of personal boundaries. This impasse is in a sense orchestrated by the inner critic, who automatically intervenes. This clash arises as personal feelings come into conflict with the expectations set by the inner critic.

Consequently, the inner critic suppresses the authentic and genuine feelings, thoughts, and sensations that arise naturally within an individual, labeling them as "bad," or "wrong." In this way, the inner critic prevents the person from expressing their genuine needs, wants, and limits. The persistent disapproval of an inner critic, judging the individual to be mean and unacceptable, impedes the adaptive facet of the self, the experiencer, from standing up to the negative evaluations.

Manifestations in Language

The interplay between the experiencing self and the inner critic is highlighted by expressions of struggle and coercion, often accompanied by a sense of confusion. For instance, individuals may articulate their internal conflict with statements like “I wish I could, but I can’t” or “I would like to, but I am inadequate."

The inner critic issues cautionary messages, such as "If you don’t lose weight, nobody will love you," or “You’ll never be able to do that; this is beyond you,” vigilantly pointing out weaknesses with statements like "You did that wrong again" and issuing imperatives like "You must stop eating." It frequently resorts to absolute terms such as “always,” “everybody,” “nobody,” and “never”.

It establishes conditional rules like "You are only lovable if you lose weight." Employs derogatory labels like “I am a failure,” and “I have no self-respect,” along with other negative evaluations like "What’s the matter with me? Why can’t I just be normal?" This self-talk signifies a perceived failure to meet personal and societal expectations, eliciting feelings of frustration, anger, and self-contempt.

Harsh vs. Low Inner Critics in Individuals

Self-critical thoughts are universal; however, their form differs from one person to another. In a study, participants were divided into two groups, a low self-criticism group and a high self-criticism group. Participants were individually invited into a room and instructed to sit in a chair facing an empty chair.

They were then prompted to recall a recent experience of failure and articulate, aloud, the thoughts of their inner critic for approximately five minutes, directing these expressions toward the empty chair in front of them. Following this period, participants were directed to reverse the chairs, placing themselves in the position of receiving the criticisms. In this role, they had to face the inner critic and respond to it.

Both the low self-criticism group and the high self-criticism group voiced critical thoughts, but notable distinctions emerged. The high self-criticism group exhibited more contempt when expressing criticism. Concurrently, they demonstrated greater submission to criticism.

Members of this group accepted the criticisms and also experienced heightened feelings of sadness and shame. They couldn't separate themselves from the inner critic, making it challenging for them to express anger, pride, or assertiveness in response to criticisms.

Meanwhile, the low self-criticism group exhibited less contempt in their critiques compared to the high self-criticism group. Moreover, members of this group confronted the inner critic, expressing anger, and even dismissing the antagonist. Consequently, the important factor is not solely the self-imposed criticisms but the individual's capacity to confront self-criticism.

Acceptance of self-critical attacks is an integral component of a depressed state. In such a state, people find themselves restricted to the critic's perspective, incapable of countering it. Navigating self-criticism in this challenging state proves exceptionally difficult, leading to pervasive feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. Beneath these emotions lie underlying fears and genuine sadness. Over time, individuals may become accustomed to this emotional state, encountering it persistently as a recurring theme in their lives struggling to break free from the constraints imposed by the inner critic.

References

Earley, J. (2009). Self-therapy: A step-by-step guide to creating wholeness and healing your inner child using IFS. Larkspur, CA: Pattern System Books.

Elliott, R., Watson, J., Goldman, R., & Greenberg, L. (2004). Learning emotion‐focused therapy: The process‐experiential approach to change. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association.

Gilbert P., Clarke M., Hempel S., Miles J.N., Irons C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. Br J Clin Psychol. Mar;43(Pt 1):31-50. doi: 10.1348/014466504772812959

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2005). Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263–325). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203003459

Gilbert, P. and Procter, S. (2006), Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin. Psychol. Psychother., 13: 353-379. https://doi-org.proxy.findit.cvt.dk/10.1002/cpp.507

Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind. London: Constable.

Greenberg, L.S. and Pascual-Leone, A. (2006), Emotion in psychotherapy: A practice-friendly research review. J. Clin. Psychol., 62: 611-630. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20252

Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. C. (2006). Emotion-focused therapy for depression. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11286-000

Shahar B., Carlin E.R., Engle D.E., Hegde J., Szepsenwol O., Arkowitz H., (2012) A pilot investigation of emotion-focused two-chair dialogue intervention for self-criticism. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19:6, https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.762

Stiegler J.R., Vildalen V.U, Heggem T., Ismaili S.B., Schanche E. (2022), The effect of the two-chair dialogue intervention on self-compassion - adding an emotional evocative component to a basic Rogerian condition, Counselling and Psychotherapy Research published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy, https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12534

Stinckens N., Lietaer G., & Leijssen M. (2013) Working with the inner critic: Process features and pathways to change, Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 12:1, 59-78, https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2013.767747

Whelton, W. J., & Greenberg, L. S. (2005). Emotion in self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1583–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.024