Attention

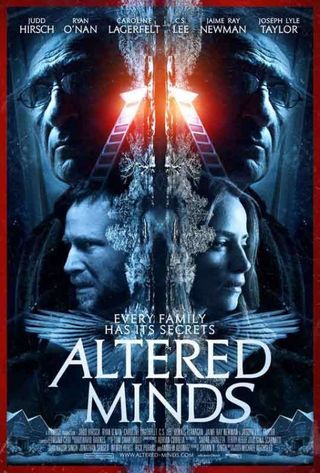

Altered Minds

Director Michael Z Wechsler talks about his new film, a psychological thriller.

Posted November 20, 2015

Altered Minds is a new feature film written and directed by Michael Z Wechsler. Let's just say that lots of things come to a head—in every sense of the word—at a family gathering as its patriarch, played by Judd Hirsch, is taking his last breaths. The film is now in theaters and available at iTunes. I chatted with the director.

This film focuses tightly on a small group of people many would call a dysfunctional family. Autobiographical in some way?

If you mean, do I come from a dysfunctional family? Well, it’s my belief that all families have varying levels of dysfunction. That’s not to say that families have the kind of abuse and secrets that the one in my film may have experienced. As a culture, the ideal of the Leave it to Beaver family unit never existed, which is probably why it was a popular show (denying imperfection fit in with the repressive values of the 50s). Even the Brady Bunch had their issues.

Speaking of my own upbringing, I was fortunate to be raised by loving parents along with two wonderful sisters, but we definitely had our share of what I would call “familial discord.” Luckily, it was nothing that would ever be sustainable or dramatic or intense to be channeled into a feature length movie like the story of Altered Minds. That being said, we had our share of family therapy, which I think was a good thing for communication. It was also my introduction to the world of psychology/therapy, which then became not only a major part of my life through adulthood but also an inspiration for many of the scripts I would later write.

The movie isn’t literally autobiographical, but much of myself lives in these characters and their struggles. Like the members of this family, I grew up not realizing that I was suffering from trauma that would follow me well into adulthood. Once a therapist explained to me that a certain seminal event in my life had been shadowing me since childhood, a lot of things suddenly made sense. The need to understand myself and how I’m a direct product of my past is very similar to my protagonist Tommy’s quest to discover the truth.

The 11/18/2015 New York premiere screening of Altered Minds was followed by a panel discussion led by Psychology Today’s Editor-At-Large Hara Estroff Marano and featured actress Caroline Lagerfelt, director Michael Z. Wechsler, PT experts Guy Winch, Ph.D. and Jane Greer, Ph.D.

Altered Minds is, at some level, driven by the mystery of mind-control experiments conducted by the U.S. government during the Cold War. Can you give us a clue to the kinds of experiments that did go on?

I’m not an expert in the history of the mind-control program. I didn’t want this film to become a history lesson about the MKUltra (mind control project), although I think Oliver Stone should tell that story and it would be fascinating. What I did learn about the CIA’s covert program was enough to create just the perfect narrative device for a compelling mystery.

I read a number of books that essentially were exposés of the United States government’s numerous experimentation programs and learned enough to realize it wasn’t science fiction or conspiracy theory delusions. Since the early 20th century, our government has conducted experiments without consent. Whether it was the Tuskegee airmen who were injected with syphilis without their knowledge or the actual mind manipulation I allude to in Altered Minds, which took place later, our country clearly crossed ethical and moral lines in the name of many things: medical research, cold war, psychological “progress”

What I learned that would fascinate and sicken at the same time was how many people (including children) were essentially robbed of their humanity, taken against their will (not unlike animals tested today), and tortured not by soldiers but by psychiatrists. The experiments were wide-ranging and really depended on the goal at hand. Many became guinea pigs for mind-altering (pardon the pun) drugs that were being tested for use on soldiers on the battlefield. Others were isolated and punished till they disassociated and split into alter-personalities that could be programmed to aims that may have had some military significance. It was the creation of the “alters” that really captivated me, not only because it was just so sickening that people could do that to each other, but that it actually even happened at all. That aspect of the MKUltra project—the disassociation and alter formation—were directly incorporated into my story.

What attracted you to writing a film about mind control?

Well when I started writing the script, it was just about a dysfunctional family whose father may have been hiding secrets. I wrote nearly half the script not knowing what that secret was but the voices of the family were so strong and the desire to make this about the mystery of the secret so pervasive, I realized I had to find something out of the ordinary. If the secret was more mundane like child abuse or incest, the mystery of the story would be much harder to create for the audience. I stumbled upon the mind control by accident while surfing on YouTube (something I highly recommend if you have writers block). I came across real congressional testimony from former victims of the mind-control experiments that former President Clinton allowed. These were people who weren’t allowed to tell their stories for decades and had long been written off as schizophrenics and conspiracy nuts, but were now, for the first time, finally being given their due by a government exposing its ugly inner workings.

As soon as I watched these, I was, myself, shocked to learn that this may have actually happened. And then, as I read more about that chapter of American history, I became not only morbidly fascinated with it, but realized I had the perfect secret to create the mystery of this story. My initial reaction, of complete disbelief, is how I wanted the film family as well as the audience to react, but then, over the course of the story, their perspective would shift and skepticism would be replaced by an ominous awakening. People watch the film with that shift in their perspective and that’s exactly how I experienced my indoctrination to the mind-control projects.

Why do you think people are so fascinated by the idea of Frankinsteinian machinery and apparatus making us do things when mind control is possible to varying degrees by many means besides frank torture (which evidence suggests doesn’t even produce desired results) and goes on all the time right in front of our eyes?

Well I think it’s fascinating because it really shows a level of human depravity that is so hard to digest, that it seems, as I said before, like science fiction. Many of the mind control doctors, not surprisingly, were former Nazi doctors given new identities and amnesty in America to continue their “pioneering” research. Hard to believe, right? Also hard to not want to learn more, how and why. There’s something so sinister about mind-control programming, essentially turning people into robots without their own will power that I think appeals to our innate desire for control and our innate fear over losing control.

The film focuses on four adult children of a dying father. Three of the children are adopted, one is biological. What was this distinction about?

Well, I think in all families, regardless of their makeup, there’s always a hierarchy for the children in which one child may get more attention and not necessarily for good reason. I believe there’s no family where there aren’t kids who feel as if they got the short end of the stick, and I think that’s a dynamic that lasts forever, even after our parents are gone. From the time we’re kids, throughout our lives we are always vying for the attention of our parent, and that is just human nature. Inevitably, that hierarchy wherein one child gets more attention than another plays itself out. In the case of Altered Minds, I created that hierarchy for purposes of conflict, and I think that the troubled adopted kids made it very natural for that power grab to exist. In the film, the father, Dr. Shellner, adopted war-torn orphans who had been traumatized beyond belief and brought them up in a house of love. In that scenario, who is going to lose out on their parents love and attention—the adopted kids who already had experienced so much loss or the biological child who has, by virtue of being the only one connected to the father/mother by blood, lost nothing? It was clear to me that creating this distinction would also strengthen the conflict between the sibilings and allow me to create suspicion in the mystery of the biological son’s motivations.

The film revolves around childhood memories—those of the four children and even those of the father. As a filmmaker, what is the appeal working in the arena of childhood memories?

Memories are cinematic. Because they are so subjective and unreliable, they make for a wonderful ally when creating mysteries or psychological dramas. Hitchcock was one of the first directors to use the foggy lens of repressed memories wonderfully in his film Spellbound. Many other directors have focused on the mind and it’s often tenuous recollection of the past to create intense films about characters trying to reconnect with their lost selves. I love films like Ordinary People, Shutter Island, and Memento that really use the idea of repressed memories to tell compelling stories.

The family, headed by a much-lauded father, is nearly destroyed by the distress of one son. Yet this son is in a way the hero. Are you giving us a new kind of figure—the psychological hero?

He’s a Byronic hero at least at the beginning of the film because he’s accusing his dying father, whom we like and trust, of doing horrible things to the kids. He causes havoc on what should be the most memorable final get-together this father will ever have with his kids. That’s not a sympathetic character. Yet, in the end, Tommy’s exploration takes this entire family out of the darkness to some extent. His tenacity and his conviction ultimately shine a light of truth on this family’s past and so, yes, he is the hero. I like the term "psychological hero" because it’s his diseased and traumatized mind that tells him all along that he has to get the answers. Through his psychological condition, he triumphs.

What perspective on families did you want viewers to walk away with?

A few things come to mind. I want viewers to consider the veneers and facades that all families seem to put up to keep the overrated appearance of normalcy intact. (That’s why we like the Addams family—they don’t put up a facade.They show us who they really are. I’d like people to think about the secrets, big and small, that have lived within the confines of their families and how that’s impacted them personally and in their relationships. I would also like audiences to consider the damage that sustaining that secret does in the long run.

And last, what question has not been asked that you would like to answer?

What are you working on next and does it have any psychological subject matter like Altered Minds?

My next film, which is currently in early preproduction, is even more strongly psychological than Altered Minds. It’s a romantic fable called Modern Primitives and, once again, it focuses on characters who are traumatized and don’t necessarily understand why. But this time the quest for understanding the truth comes through love. It’s really a far out and unique, almost hard to classify film about mental illness, past lives, and mythology.