Extroversion

Why Almost No One Is 100 Percent Extraverted or Introverted

Research on the reality of personality distribution.

Posted March 13, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- It may be handy to label people, but they usually don't fall into distinct groups.

- In most traits, high or low values are rare, with most people being somewhere around the average.

- This is because many reasons add up to why people differ.

We often label people based on one trait or another. Jane is an extravert; Mary is an introvert. Peter is a narcissist. Val has a growth mindset. John is a psychopath.

As handy as these labels are, they misrepresent reality. Using them assumes that people fall into distinct groups in the traits, but they don’t.

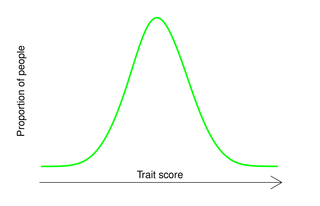

Instead, almost every trait in which people differ is a continuum, meaning that people can have any level of it, from very low all the way to very high.

Moreover, most traits have bell-shaped distributions among people, meaning that most are in the middle and more extreme values are increasingly rare. For example, most people are neither low nor high in extraversion but have some medium level of the trait.

There is a very simple reason for that.

Almost Everything Has Many Causes

People falling into just two categories in a trait would require that there be only one reason for why any two people are different in that trait. One has that cause and hence has the trait, while the other doesn’t.

But apart from very few, rare characteristics—such as Down's syndrome—there is no evidence that traits have a single cause. Instead, any two people usually differ from one another for a great variety of reasons. For example, many genes matter for which extraversion level people have. Likewise, many life experiences matter.

This means that traits can have many levels and that medium levels are usually more common than extreme levels.

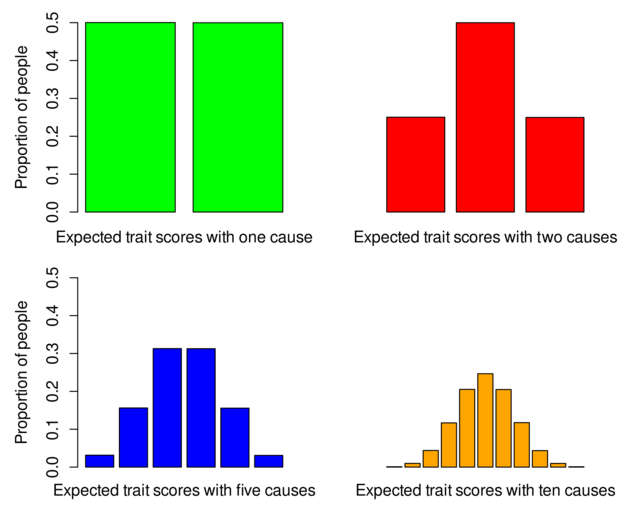

Suppose the simplest possible hypothetical scenario where a trait has only two causes, with either having a 50-50 chance of being absent or present for any given individual. This means that an individual can have three levels on the trait:

- Neither cause is present, leading to a low trait level

- Either of the two causes is present but not the other, leading to a medium trait level

- Both causes are present, leading to a high trait level

The probability that neither cause is present is 0.50 x 0.50 = 0.25, or 25 percent. The same goes for the probability that both causes are present. So, 25 percent of people have low, and another 25 percent high trait levels. Hence, 50 percent have a medium trait level, with 25 percent having the first cause but not the second and the other 25 percent having it the other way around.

In a hypothetical scenario with three causes, 12.5 percent of people have each combination of trait presence versus absence (0.50 x 0.50 x 0.50 = 0.125), and there are four possible trait levels. Specifically, 12.5 percent have the lowest level and equally many the highest level because either of these can only be achieved by one combination of causes. For the rest, 37.5 percent have the lower-medium level and equally many the higher-medium level, because there are three ways to achieve either of these levels.

The same logic extends to four and more causes, leading to ever more possible trait levels and their distribution among people, looking ever more bell-shaped. This is true even if the causes are rare or come in different levels of strength, according to the central limit theorem.

Now, imagine what happens in real life where there are many hundreds or even thousands of reasons adding up to why people differ in a trait: they can have hundreds or thousands of levels on the trait, and higher and lower values are increasingly less common.

This explains why most of us are moderately extraverted, intelligent, empathetic, narcissistic, or psychopathic. It's because many possible reasons add up to why we differ in these traits.

By and large, this also goes for many traits beyond psychology, like height, body mass index, or hypertension.

Labels Have Practical Value—But Only That

It is sometimes useful to arbitrarily group people, such as by saying that they are low, medium, or high in a trait. For example, this can be done when giving people feedback on their personality test scores. Or, this can help to explain scientific findings like the probability that your personality will change over the next few years.

This can be done to convey a message: for example, calling those with a body mass index above 25 "overweight" allows some to argue that large proportions of populations have unhealthy lifestyles, hoping to evoke behavior change. But there is absolutely nothing special about the BMI of 25 that makes having 26 worse than 24.

Doctors may do this for practical decisions: for example, if a patient's blood pressure exceeds a certain value, they are diagnosed with hypertension, and treatment is considered. But this being an arbitrary cutoff, they can easily change it once another cutoff proves more useful.

These are all just convenient groupings that don’t say anything real about nature. Likewise, there is no reason to think that nature has created introverts or extraverts. Instead, people can have all levels of the trait we recognize as extraversion, from very low to very high with the majority being somewhere halfway between these.

If we really need to use labels, we may call most people ambiverts, whatever this means for any one individual. Very few people have such a high extraversion level that we could safely call them extraverts and equally few are pure introverts.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Andrii Kobryn/Shutterstock