Neuroscience

The Mystery of Subjective Time: A Case for Embodiment

A solution to the unsolved mystery of how we sense the passage of time.

Posted December 23, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Researchers have not solved the important question of how the brain processes time.

- Experience suggests that the sense of time builds upon our bodily feelings.

- Brain imaging studies point to the insular cortex, which receives signals from the body, as important structure for the sense of time.

- We feel time passing with our bodies.

Phenomenal consciousness is a mystery. Our feelings of joy and pain, our sensing of the blueness of blue, the taste of chocolate I was craving for, all these experiences are not explainable by science. A neuropsychologist can tell you which networks in which brain regions are active when we feel pain or when taste receptors are stimulated. A physicist can explain the wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, which lie between 400 and 450 nanometers for blue light. Science informs us about what is in the world from a third-person perspective. Our experience is something different. It is the first-person (my) perspective on the world. Experience is not about the activity of nerves, about electromagnetic waves, or the outward behavior of an individual human, is it is about what it feels to me like to perceive, think, and act.

Psychology and neuroscience have made steady progress in explaining how we humans perceive (as process) and behave (as movement) from the third-person perspective. Although under constant change and revision, researchers agree on many basic facts concerning how humans see, hear, feel, think, plan, use language, and so on. The experience of time, however, remains a mystery. We feel the passage of time and estimate duration. Ten minutes without entertainment may pass endlessly, and we feel it has lasted much longer than the clock indicates. The same ten minutes spent in an engaged conversation flies by very quickly and subjectively may last only a minute. We clearly experience time. Researchers like me study time perception. But how does the brain process time? That is the question, and there is no consensus among researchers. Too many different and exclusive theories exist.

Why is that so? An answer could lie in the peculiarity of the time sense. Time is intangible. We cannot point a finger at time passage or duration as one can at an apple, a sound, or light source, or a tooth that is aching. There is no sensory organ for time perception similar to the receptors for the other senses. Sensory transduction nerves and dedicated brain regions are involved in seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, and touching. Nevertheless, we can experience time directly and sometimes unpleasantly, like when we are bored. For more on boredom, read: The Case of Boredom: Enduring Empty Time.

An analysis of the sensation of boredom could possibly provide a clue to how we sense the passage of time. When we are waiting for something to happen, to begin or to end, we intensely feel our bodily and emotional selves. We conducted such a study where we had people wait for 7.5 minutes for the experimenter to return to the waiting room. Unbeknownst to the participants, the waiting situation was the object of our study. Read about this study in Who Is Afraid of Waiting? The results were clear-cut, the more people felt emotionally awkward and negatively aroused while waiting, the longer the subjective waiting time.

Humans probably sense the passage of time and judge duration through our bodily and emotional selves. One theory about "how we perceive time when there is no sense organ dedicated to time" is that we experience time passage through our physical sensations. Subjective time could emerge through the persistence of the dynamically changing bodily self across time. Body feelings are always there. We can close our eyes, use earplugs, the sense of the body always remains. This is an idea that was initially put forward by the functional neuroanatomist A.D. (Bud) Craig, who has been studying a specific network of the body and brain: The interoceptive system, including the insular cortex, which creates the sense of the internal physical state—how we feel.

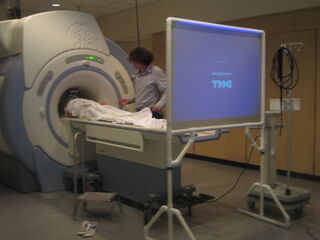

My own empirical research when I was working at the University of California in San Diego and more recent investigations by Alice Teghil from Sapienza University of Rome clearly point to the insular cortex as an important region for sensing the passage of time. In studies with the fMRI brain scanner (see the photo below), we had subjects judge time by pressing a button when they thought that a presently perceived tone had reached the duration of a previously presented tone. The insula showed to be most reliably activated as a function of accuracy in timing performance. Further studies by my team and other investigators point specifically to the involvement of the heart rate and breathing rate when we sense duration. What is more, dozens of studies point to the fact that in strongly emotional situations, when the body is active, we relatively overestimate duration. Our body creates the sense of time.

That could be the connection between our first-person perspective of feeling time passage and the third-person scientific perspective on the body and brain. Bodily processes, like the breathing cycle or the heart rate, typically have rhythmic patterns with specific frequencies. A steadily growing appetite or anger reflects a linear increase in body awareness. These physical sensations have been shown to influence perception and thought. Scores on an IQ test or my driving ability will differ, depending on whether I am calm or agitated, whether I am in a good or bad mood, whether I am hungry or not. This is the notion of embodiment: My state of mind does not depend on a calculating computer in my head, but on my brain, a physical organ of the body that is connected with the rest of the body through nerves, blood vessels, hormones, and the immune system. One could say we, with our bodies, are time.

References

Wittmann, M. (2013). The inner sense of time: how the brain creates a representation of duration. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(3), 217-223.

Craig, A. D. (2009). Emotional moments across time: a possible neural basis for time perception in the anterior insula. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1525), 1933-1942.

Teghil, A., Di Vita, A., D'Antonio, F., & Boccia, M. (2020). Inter-individual differences in resting-state functional connectivity are linked to interval timing in irregular contexts. Cortex, 128, 254-269.