Could the "self" be gone during episodes of amnesia?

Amnesia is often described as a simple problem of not being able to remember things. It's a bit more complicated than that. It often has to do with a failure of a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which helps us store information in long-term memory. It also comes with a number of additional problems as well, such as the inability to recall things that have happened in the recent past (called retrograde amnesia).

Less well know is that it is also associated with a problem of imagining ourselves in the future (Hills, 2019). Somehow being unable to encode and recall recent memories is associated with being unable to project thoughts about ourselves into the future.

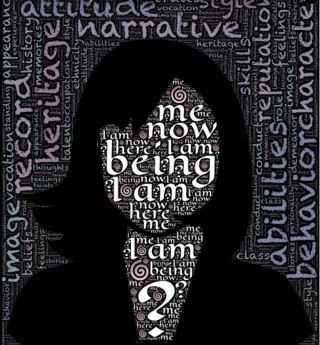

Not being able to imagine your "self" doing something is a strange problem. Does this mean that individuals with amnesia have a degraded sense of themselves?

A study discussed in Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay (1993) compared a small group of amnesic patients with another group of control participants. They watched a video where an experimenter asked questions and sometimes one of two alternative people answered the questions. Participants had to remember who responded. This is a test of external source monitoring: who said what?

In another part of the same study, it was either the participant who answered or another individual. Again participants had to remember who responded. This is a test of internal-external source monitoring, sometimes called reality monitoring: did you generate it, or did someone else generate it?

According to Johnson et al. (1993) amnesic patients were especially poor at source monitoring items they had generated themselves. They couldn't recall where the information came from when they were the ones producing it.

This is a peculiar result. As Johnson et al. put it “amnesiacs are more disrupted in self-generated, reflective memory than in perceptual memory processes.”

This looks surprisingly consistent with amnesics being unable to elaborate on their own self-generation of information.

One potential conclusion from this and other studies of amnesic patients reported in Johnson et al. is that amnesics' poor memory for self-generated information is consistent with what happens to healthy patients when self-reflection is impaired. When healthy patients suffer either from time pressure or distraction reality monitoring is impaired. When we are unable to think about the source of mentally generated information, it is harder to later to figure out where it came from. Without elaborating via self-reflection on our own thoughts, their origins become diluted. And amnesics seem to lack this ability.

The inference is that if we’re not being self-reflective when we think our thoughts, somehow registering our thoughts as our own, then their origins dissolve. Our own thoughts become no more or less tied to us than other things we hear or read.

The self disappears.

References

Hills, T. T. (2019). Neurocognitive free will. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 286(1908), 20190510.