Cognition

Choose Growth

Struggle is only part of the story.

Posted June 13, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Trauma and struggle are inevitable in our lives.

- Despite struggles, we can choose to live stories of growth.

- There are three important steps we can take toward posttraumatic growth.

So often when asked, “How are you doing today?” the answer we give is, “I’m fine.” But “fine” is almost never descriptive enough to capture the complexity of our lives. And often, we say we’re fine when in actuality we are not. The stories we tell ourselves and others in mundane conversation give us glimpses into what we believe to be true—about ourselves, about the world, and about our place in it. It also tells us what we want to be true: That we are actually fine.

These stories are our personal narratives. They are driven by individual psychological frameworks that shape how each of us sees the world. And this framework, known as our individual core belief system or “worldview,” was constructed internally by each of us. So, it follows that our core beliefs are actually open to revision by us. What this means is that when we say we’re fine, but we are not, we actually could make ourselves fine (or better) if we know how to. And that comes down to the act of choosing growth.

Harnessing the Power to Write Your Own Story

What if it became natural to answer the question, “How are you doing?” with truths about how we are struggling, but also with truths about how we are overcoming, excelling, or experiencing joy? A world like this exists for people who understand the concept of posttraumatic growth (PTG) and it’s a daily practice for those of us in the growing PTG mindset. PTG involves acknowledgement of the co-existence of triumph and tragedy in the aftermath of difficult life circumstances. It also involves a focus on the unexpected gifts that hard times bestow upon us.

A central part of the PTG process is coming to terms with our personal struggles and then choosing to pick up the metaphorical pen and write the next chapters on our own terms. To do this, we must be able to accept how things have changed and imagine how they can become better. This is easier to do if we can see the growth and beauty that often emerges as things evolve. That takes practice, but it’s being done by millions of people around the world just like you. You may even be doing it already and not realize it.

It takes effort to cultivate a mindset that can hold space for both struggle and growth, while focusing on how we have persevered and grown. And research shows that this type of work really pays off. People experiencing PTG often report reduced depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD. This is likely, in part, because of the newfound recognition that there is always a choice in how we view the circumstances of our unfolding lives. We must give ourselves permission to choose growth.

1. Understanding Posttraumatic Growth (PTG). Posttraumatic growth is the experience of growth and transformation that happens because of the really hard things we go through. This experience grows in between the frustration, guilt, sadness, discomfort, and shame that often accompany the hardest times of our lives. And it happens because the struggle in the aftermath of difficult life events disrupts the way we have seen the world, making new ways of seeing possible. When life breaks us, we have an opportunity to put ourselves back together differently, and better.

This disruption of core beliefs is usually unexpected and extremely painful, but it carves out space for a new reality. PTG shows up as deeper interpersonal connections that are made possible because of a loss. It is the compulsion to follow a new path because a traumatic event has changed the trajectory we were on, and it can be a closer conversation with God than we ever knew or thought possible before we experienced tragedy.

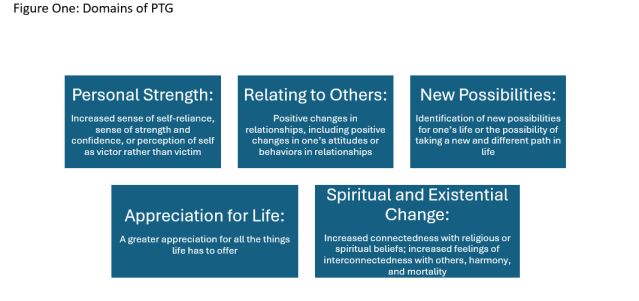

Research tells us that there are five domains of PTG that people can experience (Figure One), and growth can happen in any or all of these:

2. Using Dialectical Thinking. Understanding PTG is one step toward being able to see the “good” that accompanies the “bad” in our struggles. Being able to see things from multiple perspectives is a hallmark of PTG-oriented thinking. Therapists and counselors refer to this skill as “dialectical thinking,” and it involves the ability to shift from viewing one aspect of a situation to another. Fortunately, dialectical thinking is a skill that can be cultivated, practiced, and grown. One way to develop it is to work at seeing both the challenges and benefits of an event or situation.

For example, an event might simultaneously be the worst and best thing that ever happened to you. Consider the soldier who goes to war and loses a limb, only to come back and meet the love of his life in the recovery clinic. Without having endured the tragedies of war, he may never have met his true love. For PTG to be possible, we must be willing and able to acknowledge both the losses and the gifts that are present in really difficult circumstances. This type of thinking creates space for more flexible thought processes that can see beyond the typical labels—black and white, good and bad, sad and happy—that we are used to hearing.

3. Surrounding Ourselves with PTG-Centered Ideas and Language. In addition to understanding PTG and practicing dialectical thinking, we can shore up our chances of growing through adversity by making intentional choices about the language and ideas we expose ourselves to. Efforts to increase mental health awareness have created a world in which diagnoses and symptoms dominate the news and social media platforms. The reality is that our lives are full of terminology to describe our struggles (See: Depression, Anxiety, PTSD). But struggle is always only part of the story.

What happens if we flood our personal worlds with an abundance of words and ideas to describe how we have grown, thrived, overcome, and surmounted obstacles despite the circumstances life has thrown at us? Research tells us that this creates the conditions for PTG to occur. And increasing the presence of growth-centered language is a key step in changing the story.

One way to do this is to read about, learn more about, and listen to stories of PTG. The more we see PTG unfolding in our lives and others’, the greater chance we have of noticing it unfolding within ourselves. A second way is to notice and spend time with people who embody PTG. Conversations with strangers, acquaintances, and friends become powerful opportunities to witness growth, if we use them as such. We can also watch podcasts and interviews with people sharing their personal stories of growth after adversity that remind us of our own, and notice their descriptions of growth. Finally, we can practice using growth-oriented language when we describe and share the stories of our own lives.

You Are the Author

Words are powerful. The stories we construct and share with others about ourselves represent opportunities to highlight our struggles and focus on our triumphs. If we want to be able to tell a story of growth, we must first become aware of what our core beliefs are and come to understand how these beliefs have been challenged by adversity. Then, we must work to see where we have grown. Through this process we can influence the creation and telling of our personal narrative.

In the end, it is up to each of us to choose what we focus on. If we create a world where the language of courage, hope, and posttraumatic growth are abundant, then our story will reflect these. The Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue referred to every human as an artist, saying “Everyone is involved, whether they like it or not, in the construction of their world. So, it’s never as given as it actually looks; you’re always shaping it and building it.” By understanding PTG, using dialectical thinking, and surrounding ourselves with growth-centered ideas and language, we can harness the power to write our own stories. We can choose to see the story of growth in our lives, and to remember that struggle is only part of the story. And the story is still being written—by you.