Adolescence

4 Successive Freedoms That Drive Adolescent Growth

Priorities for new experience change as youth unfolds.

Posted July 18, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Healthy adolescents need to push parents for more freedom to grow.

- When a parent restrains this push out of concern for safety and responsibility, more disagreements can arise.

- Adolescents discover that freedom isn't free because it creates more risk and complexity to manage.

Freedom of choice is the breath of adolescent life because it allows for more independent functioning and individual expression to develop.

There is freedom for new experience and freedom from old restraint creating more youthful adventure and more youthful resistance with which parents must contend.

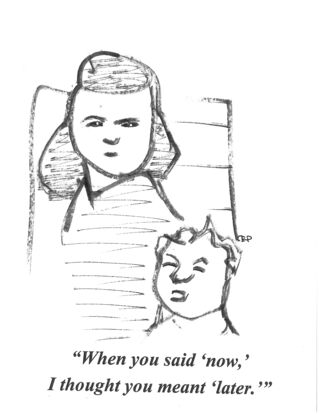

A healthy adolescent keeps pushing for more freedom to grow, while healthy parents restrain that push in the interests of safety and responsibility.

This basic conflict of interests unfolds over the course of adolescence, parents continuing to loyally hold on while they dare more letting go. As growing freedom often becomes an adolescent cause worth striving and contesting for, disagreements with parents tend to increase.

Freedom Is Costly

What adolescents keep discovering, often to their discontent, is that increasing freedom isn’t free. Not only are there new costs of responsibility to be borne, but additional freedom also makes more risks to manage, and thus adds to the complexity of life. For example, while driving a car increases independence, safely doing so takes a lot of attention and requires following traffic rules.

Then there is missing how much easier life used to be. This is a painful part of the early adolescent awakening: One can’t go back home to that simpler, sheltered, and more secure world of childhood ever again. Thus, adolescence partly begins with loss.

While parents often miss that cozy period, at times their teenagers may, too. Growing up requires giving up for everyone. Life becomes more unpredictable as limits are tested, experience is tried, risks are taken, challenges are faced, resistance is mounted, the unexpected occurs, mistakes are made, and, sometimes, hard lessons must be learned. Growing freedom makes life more challenging to manage for the adolescent and, thus, for parents, too.

Focal Freedoms Change

Over the course of adolescence, while the need for growing freedom is constant, I believe the focus of that freedom tends to alter as the young person’s developmental priorities change. In brief, these shifting freedom priorities appear to be the following:

- Early adolescence (around ages 9–13) is often focused on freedom from rejection of childhood, rebelling against younger definition: "I want to act older now."

- Mid-adolescence (around ages 13–15) is often focused on freedom of association with peers, forming a second family of friends: "I want to hang out with others my age."

- Late adolescence (around ages 15–18) is often focused on freedom with experimentation and acting older, trying to act more grown-up: "I want to see what adult experiences are like."

- Trial independence (around ages 18–23) is often focused on freedom for emancipation, becoming one’s own ruling authority: "I want to run my own life and be my own boss."

Now consider each freedom in more detail.

The 4 Freedoms

There is freedom from rejecting childhood around the late-elementary-school years, when the young person decides they no longer want to be defined and treated as just a little child anymore: “Stop babying me!” Now there is forsaking of younger interests and refusing childish treatment by parents who may find the beginning adolescent less welcoming of affectionate cuddling. In addition, she or he may become less readily compliant, more critical of less-idealized parents, and more often bored and dissatisfied, and may give up old pastimes with parents, while attraction to the world outside of home is increasingly expressed: “I want more life apart from family!”

There is freedom for associating with peers around the middle-school years, when the young person decides that forming a core group of companions to join and hang around with is now a social priority: “Peers matter most!” Now the transition from having playmates for the recreational fun of it shifts to affiliating with a group of peers for the membership and identity of it. As urgency for belonging becomes a priority, relationships can get harder. Pressures of fitting in, conforming, competing for place, and dealing with more interpersonal meanness all make relationships more challenging to maintain: “Now being with friends is how I want to spend my time!”

There is freedom and experimenting with acting older around the high-school years, when the young person decides that becoming more grown up requires starting to act like that in riskier ways to see what doing something older is like, whether one enjoys doing it, and whether one can safely get away with it, and to be able to say one has done it and to decide if it’s worth doing again: “I want to give it a try!” Daring and dating and driving, sex and substance use, partying, and part-time employment, come to mind. In the company of adventurous friends for support, one tries in group what one wouldn’t dare attempt alone: “Everyone else was doing it!”

There is freedom of emancipation into self-rule around the college-age years when the young person decides that from here on they should be their own governing authority: “Now I’m in charge!” And now the full responsibility of functional independence begins to be felt, sometimes empowering and exciting, sometimes daunting and overwhelming. Conducting a more individual and independent life from parents, free of their supervision and support, it can be hard to set and follow future direction, taking care of all one’s obligations, sometimes slipping and falling, struggling to keep one’s footing and find one’s way: “It's hard to be my own boss!”

The Parental Adjustment

Here, a reasonable question could be “How might pursuit of the four freedoms affect the relationship with parents after adolescence?” Hard to say, but perhaps one might look for the following effects with their adult child:

- From rejecting the old terms of childhood, parents can be less idealized now.

- From treating peers as favored company, parents can be less popular now.

- From risking acting more grown up, parents can be more powerless now.

- From emancipating into self-rule, parents can become more peripheral now.

Of course, none of these transformations means there has been any loss of love; only that adolescent changes do have some lasting power. As they alter the child, they alter the parent in response and, consequently, alter the relationship between them.

And the changes never stop. Thus, most parents and grown children must redefine and readjust their relationship to stay family connected as they begin conducting their adult lives more apart.

Freedom: One can't grow without it.