Stress

Low-to-Moderate Doses of Stress May Fortify Resilience

Hormesis hypothesis: Too much stress is toxic, but small doses boost resilience.

Updated May 21, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- There are 3 types of stress: eustress (good stress), distress (bad stress), and sustress (too little stress).

- Without sufficient stress, people lose their ability to cope with adversity and become less resilient.

- Hormesis refers to an adaptive sweet spot where the dose of stress is "just right."

Was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker. (What does not kill me, makes me stronger.)

—Friedrich Nietzsche, aphorism number eight from Twilight of the Idols (1888)

In the mid-19th century, a French physiologist, Claude Bernard, introduced the concept of milieu intérieur (internal environment) to describe the ability of an organism to maintain homeostasis and its "inner balance" in response to unpredictable stressors. Bernard famously said, "The stability of the internal environment is the condition for the free and independent life."

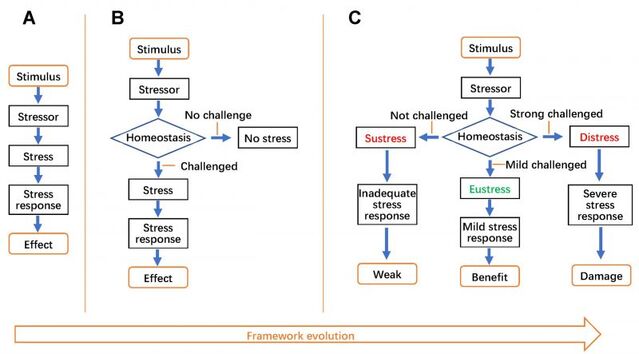

During the 20th century, research pioneers such as Walter B. Cannon and Hans Selye created stress system frameworks built on Bernard's previous work. Their groundbreaking concepts of the fight-or-flight response and general adaptation syndrome underlie how most of us view stress.

3 Types of Stress: Distress, Eustress, and Sustress

For more than a century, we've known that there's "good stress" (eustress) and "bad stress" (distress). From a psychological perspective, what differentiates eustress from distress is that the former typically feels exhilarating and is associated with a doable challenge. In contrast, the latter tends to be overwhelming and is often perceived as an anxiety-inducing threat.

But there's an often-overlooked third type of stress (or lack thereof) called sustress, which means "inadequate stress." The detriments of inadequate stress are currently taking center stage as part of a framework evolution that identifies a sweet spot of homeostasis and eustress nestled between sustress and severe doses of distress, as seen in diagram "C" below.

The Hormesis Hypothesis

As an umbrella term, stress tends to have negative connotations. Because chronic stress is detrimental to our physical well-being and mental health, there's a tendency to presume that "all stress is bad." However, the hormesis hypothesis posits that, although excessive amounts of stress can be harmful, smaller doses of distress or eustress are beneficial.

Through the lens of Friedrich Nietzsche's famous aphorism, "what doesn't kill me, makes me stronger," the hormesis hypothesis could be summed up as, "Low-to-moderate doses of stress that don't kill you, make you more resilient."

Increasingly, stress researchers are advancing the notion that optimal stress levels fall in a "Goldilocks zone"—which they refer to as the hormetic zone—between too much or too little daily stress. Like everything with a sweet spot, the hormetic zone follows the inverted-U dose–effect curve and lands between the extremes of chronic distress and a vacuum-like existence marked by inadequate stress (sustress).

The hormetic effects of low-to-moderate stress align with the Yerkes-Dodson Law, which suggests that there's an optimal level of arousal (i.e., stress) between anxiety and boredom that promotes intrinsic motivation, flow state experiences, overall achievement, and peak performance.

A Goldilocks Zone Where Stress Levels Are "Just Right"

In a recent paper (Lu et al., 2021) about the evolution of stress frameworks since the 19th century, the authors explain how excessive distress and sustress both impair optimal physiological functions whereas hormetic amounts of stress play a vital role in the adaptive process (see Figure 1, above).

As mentioned, low-to-moderate levels of stress strengthen coping mechanisms and fortify an individual's ability to thrive in the face of adversity. Notably, Lu et al. put a spotlight on how the often-overlooked phenomenon of sustress can cripple the stress system's capacity to cope with stressors.

Another recent study (Oshri et al., 2022) tested the hormesis hypothesis and found that low-to-moderate levels of stress are associated with increased resilience, better cognitive functioning, and a lower risk of psychopathology. These findings were published on June 27 in the peer-reviewed journal Psychiatry Research.

"This study provides preliminary support for the benefits of limited stress to the process of human resilience," the authors write in the paper's abstract.

"If you're in an environment where you have some level of stress, you may develop coping mechanisms that will allow you to become a more efficient and effective worker and organize yourself in a way that will help you perform," first author Assaf Oshri of the University of Georgia's Youth Development Institute said in a July 2022 news release.

Much like gradually building up calluses on your palms from lifting weights without gloves can make the skin tougher and more resilient, low-to-moderate levels of stress bolster grit and psychological resilience with repeated exposure at tolerable doses over time.

However, if your skin is rubbed too hard in a short time, it can blister before a callus forms, making it prone to pain and infection. Similarly, high levels of distress can create inner turmoil and have harmful consequences if stress doses are too high.

"Most of us have some adverse experiences that actually make us stronger. There are specific experiences that can help you evolve or develop skills that will prepare you for the future," Oshri explains. But he also warns that stress can quickly become toxic if it isn't intermittent enough or the dose is too high. "Chronic stress, like the stress that comes from living in abject poverty or being abused, can have very bad health and psychological consequences," he notes.

Take-Home Message

Finding the hormetic sweet spot of daily stress that's "just right" can be tricky. It's important to remember that too much stress can be detrimental, but too little stress also has its downsides. In general, the latest (2022) research on the hormesis hypothesis suggests that low-to-moderate stress levels are optimal because they enhance cognitive functioning and promote resilience.

References

Assaf Oshri, Zehua Cui, Cory Carvalho, Sihong Liu. "Is Perceived Stress Linked to Enhanced Cognitive Functioning and Reduced Risk for Psychopathology? Testing the Hormesis Hypothesis." Psychiatry Research (First published: June 27, 2022) DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114644

Siyu Lu, Fang Wei, and Guolin Li. "The Evolution of the Concept of Stress and the Framework of the Stress System." Cell Stress (First published: April 26, 2021) DOI: 10.15698%2Fcst2021.06.250