Gender

40 Years of "In a Different Voice"

Lessons in valuing an ethic of care.

Updated December 6, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Carol Gilligan's "In a Different Voice" showed that women differ from men in their moral judgments.

- Women tend to think more in terms of an ethic of care and relationships than men do.

- The problem with this gender difference is that an ethic of care and relationships is not valued by society.

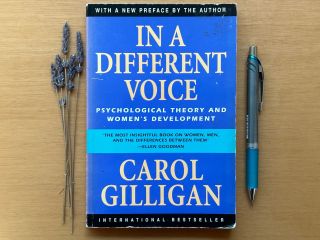

This month marks the release of Carol Gilligan’s In a Human Voice, just over 40 years following the publication of her groundbreaking text, In a Different Voice. For those unfamiliar with this classic, In a Different Voice is a multilayered book with many ways to understand its importance. Some see it as a text that helped men understand a decision to have an abortion from a woman’s perspective. Some see it as a text that challenged Kohlberg’s theory of moral reasoning that was tested initially only on boys and, thus, rigged to make men appear morally superior to women. Some see it as a text that highlighted an alternative way to think about social and political judgments from a position of care and relationships, not just justice and individual responsibility. But, to me, the important message of In a Different Voice, one that continues to frame my thinking of gender, is about gender differences.

Empowered Representations

In a Different Voice was published in a time when the feminist reaction to gender inequality was to downplay the femininity of women and to reject the ways women may be different from men, so as to demonstrate their equal potential for agency and power. This approach still dominates much current thinking about gender politics. For example, initiatives worldwide encourage women’s interest and involvement in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math), which have traditionally been male-dominated. Much media representation of women focuses on their power and great competence, from Lizzo to Oprah to Wonder Woman. These are great messages and an important change from previous stereotyped portrayals of women as debilitatingly emotional and incompetent. But do these empowered representations really just encourage women and girls to act like men and reject what being a woman has to offer?

Ethic of Care

Gilligan took the stance that women are different from men not only in biological ways (i.e., reproductive organs) but also in psychological ways. Crucially, these differences needed to be understood and equally valued as an important part of decision-making and moral judgments. The differences Gilligan observed were rooted in an ethic of care. The typical way of thinking about ethical judgments—then and now—has been through the lens of justice that focuses on individual human rights, autonomy, and reasoning. That should sound familiar and perfectly fine. But missing from this equation has been the question of relationships to others and considering others’ perspectives, interests, and feelings. Gilligan saw this view as more likely to come from women, less from men.

Gilligan did not speculate about the origins of those gender differences and did not ask whether they came from biology or from how women are taught. These origins were not important to Gilligan because the outcome was still the same: Girls and women show more of an ethic of care than men. Nevertheless, much criticism of Gilligan has focused on concerns that she essentialized women—that is, that she considered these aspects of a female morality as something that comes with being born a woman.

Essentialism

Essentialism is mostly a problem if what is being essentialized is bad, undervalued, or frivolous. Not nearly as much criticism has emerged over accusations of men being essentialized as competent, autonomous, and rational. People are more concerned about accusations of women being essentially relationship- and care-oriented. My interpretation of this difference in concern is that competence, autonomy, and reason are highly valued, and relationship and care orientations are devalued. But imagine a world where people in care-oriented fields such as teaching and nursing are paid as much as those in agency-oriented fields such as engineering and computing. That is not our world, however, so aligning women with socially devalued qualities becomes problematic.

The solution, however, is not to deny that women have a greater care orientation than men. Rather, I imagine a world where we recognize that women can offer a different way of leading, educating, thinking, and contributing that is equally valued to more male approaches. Indeed, for example, there may be some important advantages that accrue from more feminine leadership styles. But can women be equally valued as men in a world without requiring them to act like men?

In a Human Voice is a series of essays that revisits Gilligan’s work on In a Different Voice. One encouraging message from this new work is that everyone, both women and men, has the capacity for an ethic of care. Gilligan’s work raises other important questions: What if this ethic of care is applied to domains outside of the education and health care systems where we are used to finding it? For example, what if we see an ethic of care applied to the criminal justice system, to business, to leadership, to international relations? Men and women both have a capacity for an ethic of care, and I share Gilligan’s vision of a healthier and more peaceful world that integrates it and values it more.