Relationships

Building Exceptional Relationships

This single ability leads to exponential success in life.

Posted November 18, 2021 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Exceptional relationships positively contribute to our health, wealth, and happiness.

- Truth-telling, honesty, and investment in each other's learning and growth characterize exceptional relationships.

- It’s a good idea to go slow and be mindful of reciprocity as a relationship develops.

The longest-ever study on happiness has thrown the spotlight on one primary ingredient—close relationships. Whether with a spouse, significant other, other family members, friends, or larger social circle, the ability to create solid functional relationships is a determinant of both personal and professional success, finds the 75-year-long Harvard Study of Adult Development.

“Personal connection creates mental and emotional stimulation, which are automatic mood boosters, while isolation is a mood buster,” says current project director Dr. Robert Waldinger. Building relationships take effort, engagement, and time. Working from home and interacting through video conferencing are exerting a tremendous toll on our relationships.

One problem is that people don’t know how to get from contact with no connection to strong relationships or from dysfunctional relationships to functional ones. When people invest in learning how to build relationships, not only do they learn how to develop strong, robust, functional relationships, some of them become exceptional at it. This ability not only helps them become better leaders but better human beings.

Exceptional relationships are characterized by truth-telling, honesty, and investment in each other’s learning and growth. A key element of an exceptional relationship is that you feel really known. And to know that the other party also feels really known by you. To feel really known is a profoundly moving and meaningful experience.

The main challenge to an exceptional relationship is mental models—the hidden beliefs and assumptions we all hold about how we need to be accepted, liked, and successful. Our highly individualized mental models of becoming known, disclosure, sharing feelings, and feedback can become very limiting.

One of the key components of becoming known is disclosure. Typically, however, most people hold very strong mental models about whether or not it’s okay to disclose, share feelings, and give feedback. We rarely test our highly solidified beliefs and assumptions. One of the things that’s very rewarding about an exceptional relationship is that, by its nature, it constantly issues challenges, requiring you to test your mental models and assumptions. As Mark Twain used to say, a cat doesn’t sit on a hot stove twice, but it doesn’t sit on a cold stove ever again. We overlearn and solidify beliefs and assumptions, and we don’t test them.

The Stanford Graduate School of Business offers a highly popular course affectionately called touchy-feely. It is formally called Interpersonal Dynamics, taught by Carole Robin and David Bradford, authors of the best-seller Connect Building Exceptional Relationships with Family, Friends, and Colleagues. I took their course when I was at Stanford, and it is full of experiential learning in a uniquely facilitated format called T-groups. “One of the defining characteristics of a T-group is that there’s no agenda, and it’s up to the participants themselves to determine what to discuss,” says Ed Batista, a world-renowned leadership coach and an expert in leading T-Groups. The technique is hard to describe, but the lessons have stayed with me over the years.

Robin and Bradford often hear from graduates that touchy-feely helped deepen friendships, bring them closer to their families, and lead to promotions and professional success. Building and maintaining expectational relationships is an increasingly critical skill to lead, succeed, and thrive.

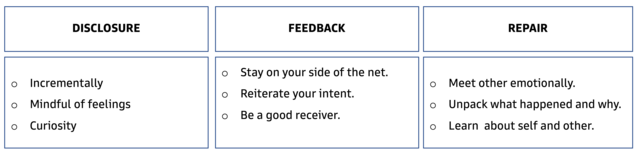

Building an exceptional relationship starts with disclosure as a means of becoming better known and allowing the other person to be better understood by you. The reciprocal action creates trust, fostering honesty with each other and the free exchange of feedback.

Disclosure is not dumping; it’s important to go about disclosing incrementally, as it involves vulnerability. But there is no meaningful relationship without vulnerability. You can play it safe, but then you’re not going to have very meaningful and enriching relationships.

Psychologist Brené Brown said it best: “Vulnerability minus boundaries is not vulnerability.” It’s a good idea to go slow and be mindful of reciprocity as the relationship develops.

Start with disclosing a little bit, seeing how the other person responds, seeing whether they reciprocate, and then continuously enlarging your comfort zone over time. The incrementalism relates to both amounts of disclosure and period. I tell you something, and then I see what you do with it. It’s not such a huge amount of information that it risks catastrophe if you do something bad with it.

After a while, you tell me something, and then perhaps I divulge something of even greater import, and then you reveal something a little bigger. That’s how relationships and trust are built. I take a little risk with you. It goes well. Then I take a slightly bigger risk. It goes well.

But suppose you now betray my trust when I’m taking a huge risk with you. In that case, both parties are whipped back to the beginning, needing to build trust all over again, and sometimes whipped back to negative territory, of having to prove oneself worthy of being trusted. Being mindful of the other person’s feelings and maintaining a mindset of genuine curiosity go a long way towards productive disclosure resulting in trust.

We also have mental models for feedback. “Oh gosh, if I tell you that something you’ve done is irritating me, then it’s going to weaken our relationship.” Well, actually, “I’m telling you that because I care about us. I think you’re better off knowing, and because if it’s irritating me, it might irritate someone else, and I care about you and think you should know because you might not know.” Isn’t that a caring and loving thing to do?

And yet, that’s not what we think of when we think about feedback. Most people don’t make their intent clear, and in that absence, negative feedback can feel ill-intended or as criticism. It’s important to reiterate your intent. And learn to become a good receiver of feedback. A simple thank you is enough to let the giver know you appreciate their feedback—no need to get into an argument or conflict, no matter how painful it may be to hear what is said with helpful intent.

Another approach you can learn to get good at giving feedback is ‘staying on your side of the net.’ or 'avoid crossing the net'. Don’t become a mind-reader. What occurs to you as the subjective reality for others is their objective reality. It's important to not assume negative intent behind the actions or behavior of others. To side-step another person who is assuming negative intent about your behavior it is important for you to reiterate your intent clearly.

David Bradford and Mary Ann Huckabay explain 'staying on your side of the net' concept this way: Most of us act like amateur psychologists in that we try to figure out why others act as they do. If you interrupt me (a behavior) and I feel annoyed (the effect on me), I try and understand why you would do that. So I make an attribution of your motives (it must be that you are inconsiderate)…

As common as this attribution process is, it also can be dysfunctional. Note that my sense-making is a guess. That is my hunch as to why you act the way you do. I am “crossing over the net” from what is my area of expertise (that I am annoyed at your behavior), to your area of expertise (your motives and intentions). My imputation of your motives can always be debated, (“You don’t listen.” “Yes, I do.” “No you don’t.”) whereas sticking with my own feelings and reactions is never debatable. ( “I felt irritated by your interruption just now.” “You shouldn’t feel that way because I didn’t mean to interrupt you.” “Perhaps not, but I feel irritated nonetheless.” )

Ed Batista notes, "so when we "cross the net" and guess at the other party’s motives, we create a plausible explanation that helps us understand their behavior, but we run the risk of being wrong--a risk that's heightened when we're in the grip of strong emotions. And if we do guess wrong, the other party will feel misunderstood, and our feedback will be perceived as unfair or inaccurate, resulting in defensiveness. The solution is to "stay on our side of the net" and stick with what we know--how we feel in response to the other party's behavior--and avoid making guesses about their motives or intentions."

Conflict is inevitable on the path to building exceptional relationships. If not managed intentionally, it can quickly derail years of trust and permanently damage a relationship. The good news is that you can learn how to repair a relationship. There are several strategies to do so. Meeting someone emotionally is a great way to start. This calls for empathy above all else. Assume the intent is positive and not malicious. Get permission to unpack what happened and why.

Most of the time, you’ll find that some form of miscommunication or misunderstanding created a problem. Leaning into conflict from the mindset of curiosity, suspending judgment, and inquiring provide a psychologically safe space for constructive dialogue. There are always things to learn about yourself and others as a result of resolving conflicts.

When you’re invested in building exceptional relationships, make it explicit, especially during the choppy phases. It helps to let the other know that you’re still there, still invested, and will keep trying. Then they can make their own decision as to whether or not they want to be engaged. If they really don’t want to, and there is no coming back, there is always hope to try again after some time has passed.

However, the best approach is to practice touchy-feely skills, so the relationships do not come to such an impasse.

Learn to build exceptional relationships and thrive in all aspects of life.

References

The Interpersonal Dynamics Reader, pages 4-5 (David Bradford and Mary Ann Huckabay, 1998)