Memory

A Better Way to Learn New Technologies

Are you trying to learn a new app? Instructional videos can help.

Posted September 9, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- When learning new technology, instructional videos may be particularly helpful for late-life learners.

- Instructional videos assist learning via content overlap, attention capture, and socially relevant content.

- Although many prefer manuals over instructional videos when learning new technology, these videos may provide better learning overall.

In the modern world, there are always new opportunities to keep learning. Whether it is the push to meet changing expectations at work, learning new caregiver responsibilities, or succeeding in courses required for an advanced degree or audited for enjoyment, the demands on us to keep growing do not disappear as we get older. In our first post of this series, we introduced several suggestions that the late-life learner can use to support new learning. In this post, we will focus on one of these suggestions: the benefits of watching instructional videos rather than relying exclusively on written text.

Instructional videos may be particularly helpful when trying to learn how to use a new piece of technology. Technology is a necessary part of daily life for many and can often be used as an aid to help us learn and remember other content. However, it can also be difficult to keep up with the rapid changes and can feel intimidating for anyone, especially those who didn’t grow up with technology as part of their daily lives.

In a series of studies supported by the Retirement Research Foundation, our lab tested ways to support those who are interested in learning new technology and who were part of generations that did not use computer technology in daily life while growing up. In these studies, participants over the age of 55 were asked to learn about the features and functions of a new smartphone application, either by watching an instructional video or reading a written manual with the same content. When asked about the application a day later, those who watched the video remembered more than those who read the manual. This benefit was greater than all other manipulations, including those in which participants were taught to use specific learning strategies while learning the application. These results suggest that no matter which strategies we use, the format that we learn from can be quite important.

Why might videos help us learn new information better than text?

- Content overlap: Effective instructional videos often have overlap between the spoken content and the visual content, and this overlap can lead to improved memory relative to reading text (Walma van der Molen & van der Voort, 2000). This overlap allows the brain to create a “dual code” (visual and verbal) for information, strengthening it in memory. Interestingly, when videos lose that overlap—such as in news broadcasts (e.g., Gunter, Furnham, & Gietson, 1984) or advertisements (Furnham et al., 1987)—adults remembered the details of the videos more poorly than written text. So even if you prefer reading a newspaper to watching the nightly news, don’t stay clear of all videos—you may still find a video of how to repair your bicycle or how to use your smartphone more helpful than reading the manual.

- Attention capture: Videos are inherently dynamic and may encourage us to be more active and engaged learners. We are naturally attracted to moving objects (Howard & Holcombe, 2010), allowing videos to capture our attention and maintain it for longer durations of time.

- Socially relevant: Another feature of videos is that they often include the voices, and sometimes faces, of the people providing instruction. This more socially relevant format may encourage us to treat the new material as more social or emotional, leading to a memory benefit as research tells us that information that is learned in a social or emotional context is remembered better (see Kensigner & Gutchess, 2017).

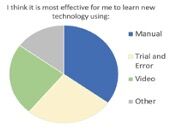

The data points to a clear benefit of watching a video to support learning new technology, but this is not the way many of us prefer to learn. In a survey of late-life learners, more reported turning to a manual or trial-and-error than an instructional video. Why do so many of us feel that written manuals are superior to videos? Our ability to search for, find, and access a video for any skill or technology that we are trying to learn is a relatively new phenomenon, meaning that many late-life learners have spent years learning new information from written manuals without the option to have a video. Therefore, we may first need to take a step outside of our comfort zone to recognize that our preferred format may not be the most beneficial if a video is available. Even if it takes a bit of practice to get used to searching for instructional videos and watching them, it is an effort that may pay off in terms of more effective learning.

References

Furnham, A., Benson, I., & Gunter, B. (1987). Memory for television commercials as a function of the channel of communication. Social Behaviour, 2(2), 105–112.

Gunter, B., Furnham, A., & Gietson, G. (1984). Memory for the news as a function of the channel of communication. Human Learning: Journal of Practical Research & Applications, 3(4), 265e271.

Kensinger, E.A., & Gutchess, A.H. (2017). Cognitive Aging in a Social and Affective Context: Advances Over the Past 50 Years. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 72(1), 61-70.

Walma van der Molen, J., & van der Voort, T. (2000). Children’s and adults’ recall of television and print news in children’s and adult news formats. Communication Research, 27(2), 132e160.