Family Dynamics

Contacting a Gamete Donor for the First Time: The Letter

You might not get a second chance to make a first impression.

Posted November 1, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Reaching out to a donor can be both exciting and stressful.

- It's imperative to put the donor or biological parent at ease.

- Be clear in communication about what might be possible as well as what isn't.

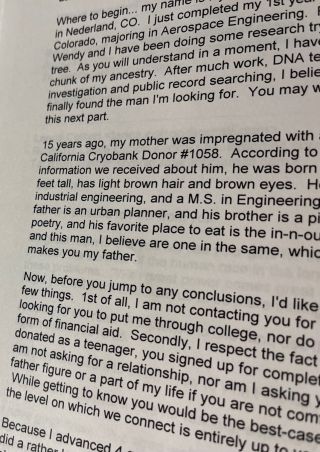

Whether you're a parent to a donor-conceived person (DCP) or a DCP yourself, contacting a biological parent (donor) for the first time can be an exciting yet nerve-wracking experience. Here are some recommendations as you prepare for your first correspondence.

Your donor or biological parent (and their family) may be experiencing deep feelings.

But just as the circumstances surrounding each child’s conception are unique, so are the variations in family structure and reactions to exploring new donor family connections. Taking inventory of comfort levels, boundaries, and openness to the ideas of expanding family are necessary steps for the formerly anonymous donor and for you, too. Allow enough time to figure out what you're seeking at this point.

If you've recently discovered your donor conception origins, have you had sufficient time to work through your emotions to incorporate this new information into your story and identity? Do you need to discuss this contact with your family? What about other half-sibling families that you have connected with? Just as others make choices for themselves and their families, this choice is yours to make.

Balancing secrecy and privacy concerns can be tricky.

Most donors were promised anonymity, but they also had no choice but to be anonymous—for 18 years or forever. While thousands of egg and sperm donors have made mutual consent contact on the Donor Sibling Registry, many more have been found via other means and have been surprised, feeling nervous or even elated by receiving that first unexpected letter from a donor-conceived person or parent. It is advantageous to send a direct letter or email, where all your thoughts can be expressed, instead of reaching out via social media (if possible), as those direct messages from unknown people are sometimes missed.

Let the donor know that you don't want anything from them.

Not time, money, or another mom or dad, for example. Be clear about your desire to know more about your own or your child's origins, ancestry, and family medical history to help fill in the missing pieces.

Are you interested in a simple exchange of information or perhaps more?

Let the donor know what type of relationship you're open to exploring, e.g., a friendship or a familial relationship. Why do you think that a connection could be fulfilling for everyone? It's often quite meaningful for a DCP to know that the donor acknowledges their existence and feels that they're someone they can be proud of.

You can let a donor know that you don’t want to disrupt their family in any way.

You only want to allow the donor to know you or your child to explore relationship opportunities and possibilities. This is an invitation, not a demand. It is important for a donor to know that they have control of the situation and that their family, boundaries, and timing will be respected.

Make the connection between biological parent and offspring.

Connecting the donor to yourself or your child by traits, gifts, and characteristics can help turn the idea of a biological child into the understanding that they have an important role in the donor-conceived person's identity.

Send photos.

This appeals to the donor’s emotions. Seeing similarities with the children they helped to create can be profound for a donor who wasn’t sure about contact. For parents, it's okay to include a letter, questions, or picture from your child.

Be positive as you express the possibilities for expanding your own or your child's family.

The tone of the letter should be very respectful, optimistic, and hopeful so that you can put the donor at ease.

Don't be afraid to reveal your excitement about reaching out.

Express positivity about the possibilities of expanding your family or even just opening up the lines of communication for medical information sharing and updates. The sharing of medical information goes both ways and can be helpful with screenings and preventative medicine and can even be life-saving as you can not rely on sperm banks and egg facilities to share new medical information.

Be specific and intentional in your correspondence.

When you are vague, the other person is left to fill in the missing pieces themselves, and if they are more skeptical by nature, this can be challenging.

Utilize humor.

Humor has a way of pulling the steam out of stressful situations, and it can help make this significant piece of correspondence feel a little more light-hearted, both for you and for the donor.

Be authentic and transparent.

Tell a little bit about yourself and your family. It's OK to be a little braggy. An appeal to a donor’s heartstrings can be helpful to make you or your child more than just a vague idea, by including information about talents, interests, hobbies, or achievements.

Drawing similarities between the biological parent and their offspring can help to make the connection more profound for a former donor. The donor needs to know that you have a full life, wonderful relationships, a career, a bright future, etc., and are not looking for the donor to fill any specific role. Any type of relationship would be a bonus.

This can be an overwhelming situation for donors who haven’t yet been contacted.

Some donors may think anonymity is still possible, may not have told their families they donated, or may have family members who are against contact. You'll want to get your foot in the door as gently as possible, reassuring the donor that you understand that they might be surprised or even shocked by receiving the correspondence and that they might need some time to process. It can be crucial for the donor to know they’re in control of the situation and the depth, breadth, and speed of the unfolding relationship.

For parents, expressing gratitude can be extremely consequential.

This can make a huge difference to a donor on the fence about connecting. Having the chance to express your gratitude can be a surprisingly profound experience.

Keep the focus on yourself or your children, even if you know about other half-siblings.

You can consider sharing that news in upcoming correspondence.

Once it's sent... breathe.

You can gently ask for a reply just so that you know the correspondence was received. But the invitation has been extended, and the process will be in motion. You can be cautiously optimistic as you test the stamina of your own patience. The potential rewards of giving a donor the option to connect far outweigh the risks. Remember, this person is very lucky that you've given them the opportunity to know you or your child.

Know that if a biological parent doesn’t reply or says “no,” it isn’t because of who you are.

It’s more likely because of their life or family situation, their lack of emotional bandwidth, or a lack of understanding of what connecting might mean for them and their family. Their hesitation might also be about their own physical or mental health issues, fear of not being “good enough,” not being at the right place in life, or other issues within themselves or their families. A "no" now may not mean a "no" forever.

If they do decline, you can let them know that if they're not ready now or need some time to process the information or convene with their family, you will be ready whenever they are. Sometimes donors just need some time to work things out internally and with their family members. If you don't receive a reply, you can try again in a few weeks or months. If they say no at that point, you'll have to give them the space to hopefully work it out and come around. Everyone needs a pause button, including donors and their families.