Child Development

Learning the Psychology of Xi Jinping to Understand China

A new book explores Xi’s childhood, career, and decision-making.

Posted November 14, 2022 Reviewed by Devon Frye

I try to read The Economist—if for nothing else, to get a view of the world that isn’t based on U.S. sources—and through this, I’ve learned Xi Jinping is central to the world stage. (For an entertaining and readable history of China across thousands of years, see Michael Wood’s The Story of China.)

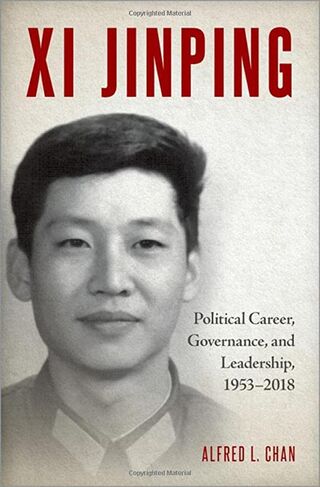

Perhaps the most comprehensive English volume on the life and career of Xi is by Alfred Chan, Professor Emeritus at Huron University College, Western University. Titled Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018, the book draws from multiple sources and social science lenses to understand the childhood experiences of Xi, and his ensuing career that has led to the present day. It provides a unique window into the psychology of Xi. What follows is a condensed interview with Alfred Chan.

Why did you write this book?

AC: First, Xi is one of the most influential players globally, and his attempts to remake the Chinese political/economic/social system will impact not only on the lives of one-fifth of humankind but also the world.

Second, Xi’s reputation is controversial, and China watchers are seldom neutral. Xi is often vilified in Western countries, but is more popular at home and in developing countries. Xi possesses a complex personality, and an exploration of the rich contrasts and nexus of his manifestations of ideology/pragmatism, humility/ambition, and insecurity/confidence set against situational and relational contexts can be useful.

Third, there was a large amount of archival materials on Xi which had not been utilized. And few authors explicitly study Xi by using the social science approach. In my view, common sense and intuition are indispensable for all forms of research, but the theoretical, conceptual, and comparative tools drawn from the social sciences can yield better explanatory value and contextualized knowledge.

What is missing from much contemporary discussion about Xi and China?

AC: First, a more objective and realistic understanding of Xi and the rise (or fall) of China. Western observers are more emotional and ideological. Missing is an appreciation of the complexity of governing one-fifth of humankind. In the last 40 years, 380 million rural Chinese have migrated into cities, creating issues of employment, social services, alienation, discrimination, inequality, and social unrest.

Second, many China watchers lack historical, cultural, and linguistic knowledge. Many rely on translations of Chinese sources. There are icebergs of information with only a tip translated. What goes on within the Politburo is relatively unknown. There are voluminous Chinese discussions by think tanks, universities, academic journals, social media, etc., on issues ranging from population pressure to urbanization, from inequality to pollution, and from corruption to maladministration.

Many often unfounded stereotypes exist about Xi as a dictator, emperor, godfather, new Mao, or one-man ruler. It’s also popular to conceptualize China as a “frozen” system under one-man rule. Xi certainly has an authoritarian side, but has introduced many progressive reforms such as poverty alleviation and judicial reform. In decision-making, Xi also depends on his colleagues for input and advice. These decisions also rely on a huge bureaucracy, which numbers about 6 million people, to implement.

Third, political scientists are concerned with power, policy analysts with the policy process, economists with supply and demand, and sociologists with social stratification. Some specialists focus on domestic politics but not foreign relations. Historians provide valuable context but seldom engage with social science theories. Each disciplinary approach may illuminate certain aspects of the Chinese reality but obscure others.

Are there any hints from Xi’s childhood experiences that may help explain his contemporary decisions?

AC:

Key childhood socialization and experiences.

First, Xi’s parents were child soldiers/activists/revolutionaries who had gone through decades of struggle before becoming the elite of the new regime. Xi’s father (frugal, doting, but strict) habitually gave homilies about toiling peasants and revolutionary struggle to his children. Xi’s mother was a professional woman whose career necessitated working away from home, and her children were placed in boarding schools. Xi was socialized with Maoist values.

Second, Xi’s princeling childhood featured hopes and optimism for a new China. Born of privilege he was exposed to politics at the top, and harbors a sense of entitlement as well as a sense of mission, obligation, and paternalism (to “serve the people”). Xi rubbed shoulders with top leaders and their children in Zhongnanhai and at a summer retreat at Beidaihe.

Third, adversity. Xi felt a deeper appreciation of the vicissitudes of power that include authority, hardship, and humiliation. He was aware of China’s poverty, scarcity, and underdevelopment. Xi had barely enough to eat at boarding school during the Great Leap Forward famine. China was largely a peasant society. In 1962 Xi senior was purged and Xi’s mother was harassed and driven out of Beijing. The couple’s three children were left to fend for themselves.

On contemporary policy decisions that may be related to Xi’s childhood experiences.

The highest priority is economic growth and development, improvement of the standard of living, and catching up with the West. Xi has unleashed many anti-poverty programs. Xi’s China Dream and Rejuvenation program calls for doubling the GDP per capita by 2035 and the turning of China by 2049 into a country with a modernized political, economic, and social system. Xi draws from socialist principles to address many forms of inequality.

Xi sees the CCP as a leadership vanguard to spearhead development and change. Many Western observers still harbor the misconception that the CCP is a conspirational, revolutionary, secretive, and violent class party, but today it is a modernized big tent party whose 98 million members consist of managers, technicians, party-state officials, farmers, workers, women, minorities, etc.

Xi is keenly aware of the fact that China is still a developing country. This confers China with a “high-income status” but there is still a large gap with that of the developed West. Thus, Xi endeavors to enhance China’s international position commensurate with its newfound capabilities and security needs; and move China closer to the center stage of world affairs so that the Chinese will no longer remain second-class citizens globally.