Attention

What Does It Take to Recognize a Face?

A new study reveals the power of prior exposure despite appearance changes.

Posted May 28, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Our ability to recognize familiar faces is remarkable; but we struggle with unfamiliar faces.

- A new study compared performance in matching pairs of familiar human faces, unfamiliar ones, and monkey faces.

- We turn out to be as poor at matching unfamiliar human faces as we are at matching monkey faces.

Humans have an uncanny ability to recognize faces. Decades of research on the topic have revealed how good we are at recognizing faces across changes in viewpoint, expression, even age. We learn to recognize thousands of faces over a lifetime, and most of us have no problem distinguishing familiar faces from unfamiliar ones.

However, research has also pointed to important differences between familiar and unfamiliar face recognition. When we are asked to recognize a familiar face (for example, a well-known celebrity), we can do it with incredible ease, and we are not easily fooled by changes in surface appearance, such as changes of makeup, accessories, or hairstyle.

In contrast, when we are asked to recognize an unfamiliar face, the process is much more prone to error. For example, recent work by Sandford and Ritchie (2021) found that when people are presented with an array of photos of two unfamiliar individuals and asked to judge how many different people are depicted, they tend to greatly overestimate the number of different identities present. That is, multiple different images of the same unfamiliar face are frequently judged as depicting different people.

Human and monkey faces

To investigate just how poor our ability to match unfamiliar faces actually is, a new study by Ritchie, Flack, and Maréchal (2023) compared people's ability to match familiar human faces, unfamiliar human faces, and monkey (Barbary macaque) faces.

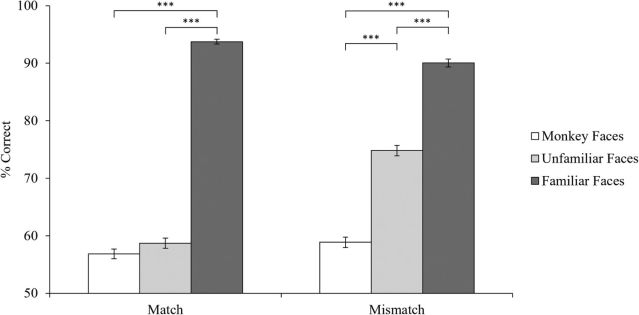

In the experiment, participants from the U.K. were shown pairs of faces and were asked to judge whether they depicted the same or different individual. The results revealed something surprising: The familiarity of the face (rather than the species) was the most important predictor of performance. The results of their study are depicted in the graph below:

Specifically, Ritchie and colleagues found that (1) participants were excellent at judging whether pictures of familiar faces (in this case, U.K. celebrities) were of the same individual, (2) participants struggled to judge whether pictures of unfamiliar faces (celebrities from other countries) were of the same person, especially when the faces were the same identity ("match" condition in the figure above), and (3) participants were nearly at chance at judging whether two monkey faces were of the same identity.

The most striking result is that performance with matched unfamiliar faces was just as poor as performance with monkey faces. This suggests that our superior performance at recognizing human faces really depends on familiarity and the type of judgment we are asked to make. Two different photos of the same unfamiliar face are just as difficult to match as two different photos of the same monkey face.

On one hand, these results reveal that our prowess at face recognition is limited; it requires some amount of experience and familiarity. On the other hand, the results also highlight the remarkable changes in recognition that result from experience.

A previous study by Baker, Laurence, and Mondloch (2017) showed that people need only one minute of exposure to become familiar with a face. Whether it involves looking at different photos of an individual,or watching a short video of an individual talking, a single minute of exposure to an unfamiliar face led to substantial improvements in face-matching performance.

The research highlights the ease with which unfamiliar faces can become familiar and the degree to which the increase in familiarity transforms our ability to recognize them across natural variations. It remains unknown whether similarly brief exposure to a monkey face would also lead to similar improvements in recognition.

References

Sandford, A., & Ritchie, K. L. (2021). Unfamiliar face matching, within-person variability, and multiple-image arrays. Visual Cognition, 29(3), 143-157.

Ritchie, K. L., Flack, T. R., & Maréchal, L. (2022). Unfamiliar faces might as well be another species: Evidence from a face matching task with human and monkey faces. Visual Cognition, 30(10), 680-685.

Baker, K. A., Laurence, S., & Mondloch, C. J. (2017). How does a newly encountered face become familiar? The effect of within-person variability on adults’ and children’s perception of identity. Cognition, 161, 19-30.