Stress

Is It Possible to Become Compulsive About Stress?

A behavior that may lead to serious health consequences.

Posted June 5, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Stressful situations have an effect on brain chemicals like dopamine and cortisol.

- Stressors can stimulate the neural circuitry underlying wanting and craving, just like drugs do.

In the final episode of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Midge Maisel a standup comic with a long and successful career, is meeting with her staff. She asks them: “Ok, what is on the schedule for next week?”

One of her staff answers, “Well, Monday you have a showcase, Wednesday you’re flying to Vegas, Thursday through Saturday you have a limited run at the Bellagio, Sunday you fly back.

“What about Tuesday, Midge asks?”

Gleefully, the staffer replies, “Tuesday you rest.”

Midge looks astonished, then clearly annoyed. In response, the entire staff looks frantically at their electronic devices, scrambling to find something for their boss to do. Clearly, Midge does not know what to do with herself when she is not busy or stressed. Surprisingly, she is not alone.

According to a 2015 study by the American Psychological Association, 24 percent of Americans experience extreme stress regularly, and stress levels have been steadily increasing over the last decade.

“Stress addiction isn’t a diagnosis,” according to Michael McGrath, M.D., a psychiatrist who is board certified in addiction medicine. It is not recognized in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. However, it is still possible to develop a compulsion toward stress or stressful situations. Such behavior affects the networks of the brain’s risk-reward system. It’s a disorder involving a pattern of repetitive and compulsive actions that aren’t related to the use of a specific substance.

Stressful situations, like learning you have a serious medical diagnosis, preparing for a final exam, or giving a presentation to an auditorium full of strangers, have an effect on brain chemicals like cortisol and dopamine. Some people enjoy the feelings these hormones produce, particularly the dopamine effect. This increases the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated.

Why Is Dopamine So Special?

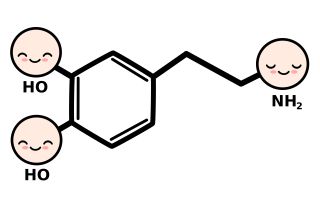

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter. Made in your brain, it acts as a chemical messenger, communicating messages between nerve cells in your brain and the rest of your body. It plays a role in the brain’s “reward center as well as in many body functions, including memory, movement, motivation, mood, and attention. Abundant research has documented the important role that dopamine plays in promoting recurrent behavior.

For example, a study published in Science described research in an animal model that proved Thorndike’s law of effect. This law states that actions that lead to reinforcements tend to be repeated more often. Reinforcement relies on dopamine activity in an area of the brain that causes animals to shape their behavior to receive dopamine stimulation.

In humans, dopamine is known as the “feel-good” hormone. It gives you a sense of pleasure and enhances your motivation to engage in behaviors that cause you to feel pleasure. From an evolutionary standpoint, dopamine rewards you for doing things you need to do such as eat, drink, and reproduce.

On the other hand, some maladaptive behaviors also cause a surge in dopamine, making it more likely those behaviors will be repeated and sometimes become deep-rooted. Junk food and sugar trigger the release of a large amount of dopamine into your brain, which gives you the feeling that you’re on top of the world and you want to repeat that experience. Some of the maladaptive repetitive behaviors that we treat in psychiatry are also tied to the pleasurable release of this hormone. Other examples are compulsive gambling, porn use, video gaming, and over-exercising.

How Does This Explain Stress?

Hans Selye defined stress as “the body’s nonspecific response to any demand, whether it is caused by or results in pleasant or unpleasant stimuli.” Once a stress response is activated (by a threatening or even non-threatening stimulus), our body pumps cortisol, adrenaline, and dopamine into our system to help us survive what feels like a life-or-death situation. It summons our body to turn off nonessential functions to route essential resources into our muscles and brain. Imagine you were being chased by a man-eating tiger—an elevation in body temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate would assist you in fleeing from danger. But, for some of us, the stress response becomes so habitual we seek more and more stress, such as overworking, to achieve that heightened state. Because stress isn’t just a mental reaction but also a physiological one, the “high” that stress causes can become compulsive.

Neuroscientist Jim Pfaus opines, “By activating our arousal and attention systems, stress can wake up the neural circuitry underlying wanting and craving—just like drugs do.” Once we become accustomed to a higher degree of stress, it may seem necessary to feel that way all the time. The brain will seek out more of the “feel good” chemicals to maintain the same stress level, which may require ever greater amounts of stimuli over time.

In their excellent book (in press) Raising A Kid Who Can, Catherine McCarthy, M.D., and colleagues write: “Experiencing stress may actually have positive correlations with life span. Stress can prime the brain for action, attention, learning, or retrieval, and researchers at the University of California at Berkeley have shown that moderate stress levels can increase cell growth in an area of the brain called the hippocampus.”

However, too much stress can cause significant risks to health. According to researchers at the Mayo Clinic, long-term activation of your stress response system and overexposure to cortisol and other stress hormones can have a negative impact on almost all your body's processes, which puts you at increased risk of significant medical conditions such as anxiety and depression, gastrointestinal disorders, headaches, muscle tension and pain, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and sleep disorders. It also places you in the higher risk category for other problems such as eating disorders, substance abuse, and alcoholism.

Clues That You May Have a Problem

- If you can’t sit still or relax, it may be a sign. You feel like you’re always chasing the next high or find yourself constantly seeking out new or exciting experiences.

- If you constantly feel anxious, overwhelmed, or on edge, it’s a sign that stress has overtaken your life.

- If you’re constantly tired, even after a good night’s sleep, it may be a sign that your body is struggling to cope with stress in your life. To concentrate, you rely on more caffeine to get through the day.

- You’re sick more often: Chronic stress can weaken your immune system, making you prone to illness. If you already have a medical condition, particularly an autoimmune disorder, you may notice a worsening of your symptoms and find it harder to recover from any new illness you experience.

What You Can Do

I treat my patients holistically and have developed the following pneumonic which has proven useful: MENDS.

M=medication when indicated. Individuals suffering from chronic stress may benefit from various types of anti-anxiety medicine or low-dose antidepressants. This would require a consultation with a psychiatrist.

E=exercise. Exercise decreases anxiety and depression. In a November 2022 post on this blog, I reviewed some of the positive effects of exercise on mental health. They include an increase in your sense of self-worth, self-confidence, sleep quality, and life satisfaction. Exercise has anti-inflammatory effects. The antidepressant effects of exercise are associated with neurogenesis—the process by which your brain increases the number of brain cells. In addition, exercise is positively associated with increased neuroplasticity—the ability of the brain to form new connections and pathways and change how its circuits are wired. Exercise decreases stress hormones. The more your fitness improves, the better your body becomes at dealing with physical stress. This means less cortisol will be released during exercise and, more importantly, in response to emotional or psychological stressors.

N=nutrition. A healthy diet can reduce stress in several ways. Comfort foods, like a bowl of warm oatmeal, boost levels of serotonin, a calming brain chemical. Other foods can cut levels of cortisol and adrenaline, stress hormones that take a toll on the body over time. A healthy diet can help counter the impact of stress by reinforcing your immune system and lowering blood pressure.

D=Dhyana. Taken from Hindu, it means contemplation and meditation. According to an article in the American Psychological Association, researchers reviewed more than 200 studies of mindfulness among healthy people and found mindfulness-based therapy was especially effective for reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. Mindfulness can also help treat people with specific problems including depression, pain, smoking, and addiction.

S=sleep. Prioritize your sleep: Disturbed sleep can negatively affect many medical conditions, including cardiovascular health. Studies show short sleep duration or poor sleep quality is associated with high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, and atherosclerosis. Habitual short sleep increases the chance of cardiovascular events. Stress and sleep disturbance are intimately linked. When you are stressed, your sleep quality is disturbed, or you may not sleep enough. The opposite is true as well. If you sleep poorly, it will worsen your stress level. Go to bed and wake up at the same time every day, weekends included. The American Heart Association recommends sleeping in a dark, quiet place set at a comfortable temperature. It is important to ban electronic devices from your bedroom and avoid caffeine, alcohol, and large meals before bedtime.

References

American Psychological Association. (2019, October 30). Mindfulness Meditation: A Research-Proven Way to Reduce Stress. American Psychological Association.

Athalye, V. R., Santos, F. J., Carmena, J. M., & Costa, R. M. (2018). Evidence for a neural law of effect. Science, 359(6379), 1024–1029.

Mayo clinic staff. (2021, July 8). Chronic stress puts your health at risk. Mayo Clinic.

McCarthy M.D., C., Tedesco PhD, H., & Weaver MSW, J. (2023). Raising a Kid Who Can Simple Strategies to Build a Lifetime of Adaptability and Emotional Strength (p. 101). Workmans Press.

Sinha PhD, R. (2013). Stress as a common factor for obesity and addiction. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 827–835.

Trachman MD, S. (2022, November 8). How Exercise Can Benefit Our Mental Health | Psychology Today.

What is Dopamine? (n.d.). Mental Health America.

Yong Tan, S., & Yip, A. (2018). Hans Selye (1907–1982): Founder of the stress theory. Singapore Medical Journal, 59(4), 170–171.