Emotions

Even a Superhero Can Cycle Between Delirium and Despair

Daredevil's extreme mood swings are a cause for concern as well as a warning.

Posted December 26, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Just as he swings around New York City, Daredevil has mood swings from ecstatic highs to depressive lows.

- Some variation in emotional state is normal, but cycling from extreme highs and lows signals a deeper problem.

- Cyclothymia is less extreme than bipolar disorder than still requires professional attention.

Given everything we’ve seen in the first three posts on the early days of Daredevil—his persistent doubts about his value, worsened by his excessive feelings of responsibility, leading him to question continuing as Daredevil at all—we would not be surprised that Matt Murdock is often sad and morose, if not depressed. We can add to this intense feeling of loneliness and isolation, not only romantic—after realizing the danger he would put a love interest, he spouts overwrought lines like, “Where Daredevil walks, he must walk alone! Thus do I accept my lonely fate!” (Daredevil #5, December 1964)—as well as more basic feelings of not having anyone to confide in about his secret life (especially when, in the early days, no one else knew about it).

Not only does all of this hit Matt harder than most superheroes, due to his passionate nature, but his periods of deep sadness are also contrasted with periods of exuberant joy. As we noted in the last post, Daredevil is the rare superhero who truly enjoys being a superhero. In an early issue, after he returns to New York City from an overseas adventure, he swings around the city, saying:

How I’ve longed for this marvelous moment—to be back in action again—free as a falcon, with the world at my feet! This is where I belong! This is my food, my drink, my life! This is why Daredevil was born! (Daredevil #15, April 1966)

The particular elation expressed here may reflect the fact that Matt has to practice extraordinary restraint in his “civilian” life, hiding his enhanced senses as well as his athleticism, so his time as Daredevil allows him a unique freedom and release.2 We see scenes like this several times in the first couple decades of his book: In one, many years later, he thinks to himself while running through the city, “What a gorgeous morning! Wind in my face… summer sun at my back… all the endless city sounds like a brass band below me… You’re beautiful, New York. I love you” (Daredevil #178, January 1982).

Emotional Cycling

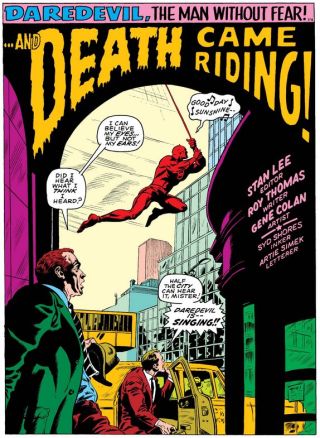

However, many of his most enthusiastic expressions of happiness come very quickly after intense periods of sadness. For example, after Matt fakes his death to thwart the blackmailer Starr Saxon, who then falls to his death—as we saw in the last post—we would expect Matt to be relieved, but he’s positively ecstatic. In the next issue, onlookers can’t believe their eyes when Daredevil swings overhead… singing all the while (Daredevil #56, September 1969). Later, after a tense episode with Bullseye on the subway tracks when he’s tempted to let his homicidal foe die—but doesn’t—Matt is seen running through the city with a huge smile on his face, joking with strangers, before beating up guys for information (Daredevil #170, May 1981). In the very next issue, after Bullseye kicks him out the window of a skyscraper, we see Matt sitting in the park with Heather, the two of them dancing like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (Daredevil #171, June 1981).3

There are two ways to look at this behavior. On the bright side, he could be balancing the more difficult parts of his life with moments of joy and abandon, which would be healthy. But the shifts seem too extreme, and suggest that he’s cycling from extreme lows to extreme highs, neither of them moderating or converging to a steady middle over time, resembling cyclothymia, which causes emotional ups and downs, although not as extreme as the ups and downs seen with bipolar I or II.

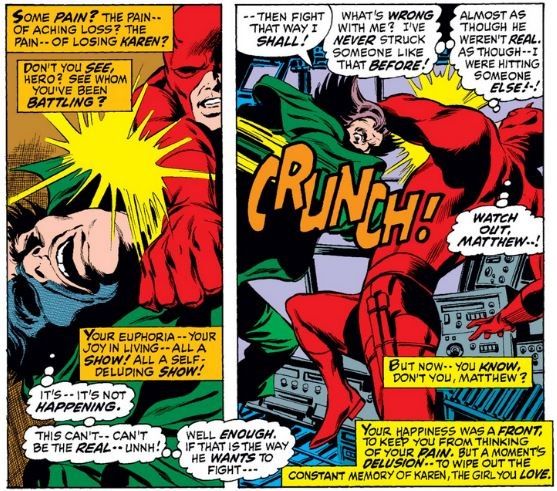

This is supported by one of the most disturbing episodes in Daredevil’s early years (from Daredevil #80, September 1971). After Karen has apparently left him for good to be a Hollywood actress, Matt seems to have found serenity, thinking to himself, “Peace, DD. Just a few minutes… of peace. Can you dig it, hero-man? No worries… not a one! It’s been the kind of day—that makes you forget all the others.” (If you want the read “can you dig it, hero-man” as a cry for help, that’s your call.) He begins to wonder if he ever really loved Karen, then catches himself and thinks, “Forget it! Matthew, old son, you’re feeling good—and it’s a feeling you want to feed.” He seems grateful for this good mood while trying not to question it: “Maybe it won’t last! Maybe in an hour, I’ll be bleeding again. Sure. Maybe in an hour I’ll be dead… Point being: Matthew, you just don’t care! You’re happy. You’re alive. And you’re livin’!”

As revealed by the narration later in the issue, his exuberance was not only short-lived but illusory:

Your euphoria—your joy in living—all a show! All a self-deluding show! You know, don’t you, Matthew? Your happiness was a front, to keep you from thinking of your pain. But a moment’s delusion—to wipe out the constant memory of Karen, the girl you love.

He comes to this realization while battling the Owl, who leaves Daredevil hanging from a damaged helicopter that explodes before plunging into the Hudson River—all of which Karen watches on television.4

Even worse than the possibility that Matt may have died is the insinuation of the accompanying narration that he might have too easily accepted his fate, taking the opportunity for “a final escape” to end his pain once and for all:

All day—you’ve been escaping, Daredevil. First into a false joy… and then into battle. Escaping—from a vision of a love that is no more…! And now you’re making the final escape… an escape even you can’t survive… In a moment, it’ll be over for you, Matt Murdock. Over for one man. Over for a small part of this greater tragedy—

This impression is reinforced at the beginning of the next issue (Daredevil #81, November 1971), when Daredevil is shown sinking into the water, pondering his regrets, reconsidering what he could have done differently—but not making the slightest effort to swim or survive, until he eventually loses consciousness. The Black Widow saves him just in time, but we are left to wonder: Did he really want to be saved?

Nonetheless, Daredevil springs back into action by the end of the issue, working with the Widow to defeat the Owl. At the opening of the next issue, he is back to swinging around the city, taking risks and barely surviving them, all the time saying things like “what’s life for, if not high living?” (Daredevil #82, December 1971). If Matt Murdock had achieved a healthy balance between happiness and sadness, ups and downs, you would think he would take more time to recover after a passive suicide attempt—but instead, the pendulum swings all the way to the other side, as it often does.

Reaching the Breaking Point

Matt’s most well-known breakdown came years later in the famous “Born Again” storyline (Daredevil #227-233, 1986), after Karen Page, down on her luck, sells Daredevil's secret identity for drugs and it makes its way to the Kingpin, who then systematically dismantles Matt's life. Our hero prevails at the end, leaving Matt free to begin a new life with nothing but his values and principles—and Karen, whom he has forgiven—but his troubles soon return. Over the next decade, he once again fakes his death, adopts a new identity, and suffers a period of dissociative identity disorder. This all reaches its climax in Daredevil #350 (March 1996), when Matt somehow manages to resolve his various identities, experiences, and actions in one stable persona… for the time being.

What can we take from this? Most obviously, if anyone in the real world experiences such wild mood swings, especially to the point where they’re thinking about ending their life, they should seek professional counseling. But even if we don’t come close to this, we should be aware of even mild changes that are out of the ordinary, either for sustained periods of time or in recurring cycles. Although a range of emotional experiences is necessary for a full and rich life, too much gyration can interfere with that. Over time, we need some level of stability in order to manage our lives through the ordinary ebb and flow and to deal with the occasional severe highs and lows.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

1. This post and the others in this series are adapted from my new book, A Philosopher Reads... Marvel Comics' Daredevil: From the Beginning to Born Again (Ockham Publishing 2024).

2. I thank Daredevil expert Christine Hanefalk for this insight. Related to this, Hanefalk addresses the possible issues with Matt’s efforts to “pass” as a blind person without enhanced senses in her blog post, “Faking It with Matt Murdock”; see also her book Being Matt Murdock: One Fan’s Journey into the Science of Daredevil. For a philosophical discussion of the more typical case of passing in reference to disability—written from the perspective of a legally blind person—see Adam Cureton, “Hiding a Disability and Passing as Non-Disabled,” in Adam Cureton and Thomas E. Hill, Jr. (eds), Disability in Practice: Attitudes, Policies, and Relationships, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 18–32.

3. For more discussion of Matt’s refusal to let Bullseye die on the subway tracks, as well as his penchant for beating up or even torturing people for information, see my book, most of which is about Matt’s ethics. (My posts here have been drawn from the last two chapters, which focus more on his mental state.)

4. Matt's self-delusions about his own happiness are also a central theme of the run beginning with Daredevil, vol. 3, #1 (September 2011).