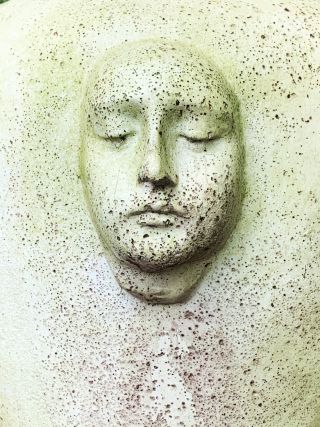

Grief

A Grief That Never Ends: Chronic Sorrow

What does it mean to continuously live with a heavy heart throughout one’s life?

Posted December 14, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Chronic sorrow is a continuous grief response to non-death-related loss experiences which are reoccurring in nature.

- Living a cyclical experience of loss, uncertainty, and disequilibrium is exhausting and disorienting.

- People who experience chronic sorrow often benefit from the presence of people who can companion alongside them over a long duration of time.

Chronic sorrow refers to a grief response to a non-death-related loss experience that permanently changes one’s life, specifically where the loss experience itself is reoccurring in nature. Chronic sorrow is defined by a pervasive sense of sadness, disruption, and grief. It is the chronicity of feelings that differentiate chronic sorrow from other types of grief, and it is often referred to as a living loss, as it requires a grieving person to continuously readjust their life.

Chronic sorrow is a unique form of distress, as there is no foreseeable end to the loss experience, and it often has a traumatic onset. This term was popularized by an American psychotherapist, Susan Roos, and it was originally introduced by Simon Olshansky in the early 1960s. Olshansky originally utilized the term chronic sorrow to identify the type of distress parents experienced after the birth of a child with a disability.

While it is important to acknowledge that raising a child with a significant disability can be a privilege in many ways, it is equally important to identify how this parental experience can come with many losses for parents who must provide continuous care for the rest of their lives. For parents, there can often be grief around having a child who does not meet sociocultural developmental milestones, and there may be grief for the loss of life as it once was, along with losses around dreams or hopes for the future. Other examples of chronic sorrow may include:

- When a devastating injury, chronic illness, neurodegenerative disease, or any untreatable health condition occurs

- Becoming a long-term caregiver to a spouse or family member

- Experiencing ecological and environmental related grief as the Earth is continuously destroyed

- Situations involving drug addiction, chronic pain, or extreme personality change, or when we (or someone we love) loses an important aspect of their identity

With these types of losses, it is often exhausting and grueling to have to continuously reenter a state of uncertainty and disequilibrium. Additionally, there can be a painful discrepancy between reality and the situation one is in, versus what continues to be hoped for. Chronic sorrow causes significant chaos and dysregulation within a family, and often individuals struggle to find a sense of coherence or meaning within this cyclical loss experience.

Unfortunately, many people who experience chronic sorrow also experience disenfranchised grief, as there is often no societal support, guidance, recognition, or rituals for this type of non-death-related loss. Given the relentless nature of chronic sorrow, many friends and family members also become burnt out in supporting the griever. This often contributes to feelings of isolation for the grieving person, and what feels to be an impossible situation can become even more disheartening and lonesome.

Typically, there are both predictable and unpredictable stressors associated with chronic sorrow, and at its core, chronic sorrow really means to continuously live life with a heavy heart. However, it’s also important to note that people don’t perpetually exist in a state of despair when experiencing a living loss like chronic sorrow. Rather, a person’s grief naturally ebbs and flows; there will be both good days and bad days. Temporary reprieve is possible.

Chronic sorrow is an understandable (and non-pathological) response to having to face a significant loss experience repeatedly throughout one’s lifespan, and this enduring pain, unfortunately, brings us into the wilderness of grief. However, many who undergo chronic sorrow are surprised to learn how grieving can facilitate greater depth, growth, and maturity. It is possible for devastating losses to co-exist with experiences like connection, joy, and even a sense of meaningfulness in life when people have access to the right support.

People who experience chronic sorrow typically benefit from others who can companion or walk alongside them. This means spending time with people who do not try to take their pain away but can rather acknowledge their grief and hold space for them. People who can offer presence, stillness, or who can witness grief are often great resources for those who experience chronic sorrow. It is important to maintain long-term social connections with people experiencing chronic sorrow, given that this is a living loss that may occur throughout one’s entire lifespan. People experiencing chronic sorrow frequently benefit from intentional grief support from friends and family, and/or professional grief counseling with a licensed therapist who's skilled in supporting more complex grieving experiences.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Harris, D. (2020). Non-death loss and grief: Context and clinical implications. Routledge.

Roos, S. (2018). Chronic sorrow: A living loss (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Rossheim, B., & McAdams III, C. (2010). Addressing the chronic sorrow of long-term spousal caregivers: A primer for counselors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88 (4), 477–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00048.x

Shelvock, M. (2022). Grieving when no one has died. Psychology Today.

Shelvock, M. (2022). Relearning the world through grief. Psychology Today.

Shelvock, M. (2022). There is no step-by-step formula for grief. Psychology Today.

Shelvock, M. (2022). What's the difference between grief support and grief therapy? Psychology Today.