Addiction

Weakness of Will and the Persistence of Stigma

People are often criticized for being weak-willed. We should stop saying this.

Posted August 11, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Judgments of weakness of will appeal to our own judgments about when it is good or appropriate to make a change of intention.

- If weakness of will is simply a propensity to revise one's intentions more readily, then there is nothing inherently bad about it.

- Someone whose will is more changeable may be more alive to the more contingent and ephemeral of life's benefits.

It is common to criticize people for being "weak-willed." This term is applied widely: to a person who goes off their diet, to a soldier who quits halfway through basic training, or to an alcoholic who will not stop drinking. This raises a couple of questions. First, what does it mean to say that someone is weak-willed? Second, why exactly is this supposed to be a criticism?

Begin with the first question. The philosopher Richard Holton has argued that there are, in fact, two very different phenomena that have been described as "weakness of will."

Inconsistency Versus Changeability

On the one hand, "weak-willed" can be used to describe acting against one's better judgment. If I believe that I should not eat a second cookie, and I eat it anyway, then I am "weak-willed" in this sense—my actions are inconsistent with my professed judgments. Call this the "inconsistency view" of weakness of will.

On the other hand, it can be used to describe a kind of vacillation in one's choices. If I resolve to not eat a second cookie, and then have a change of heart and decide to eat one anyway, then I am "weak-willed" in this sense—my will shifts from one choice to another. Call this the "changeability view" of weakness of will.

Holton observes that philosophers have tended to endorse the inconsistency view. But he argues that it is the changeability view that is closer to our ordinary conception of weakness of the will, and that better deserves that name. After all, weakness of the will is, in the first place, a property of the will—that is, of the choices we make and the intentions we form.

But consider now our second question. Why does someone who is weak-willed in this sense deserve criticism? What exactly is supposed to be bad about weakness of will?

If the inconsistency view were true, then this question might have an answer. Acting against what one judges one ought to do is arguably irrational, and irrationality attracts criticism. But if weakness of will simply involves making changes in one's intentions, what is the criticism? There is no irrationality, after all, in a change of plans.

Holton acknowledges there that there is an inherently evaluative element to our judgments here. He observes that we judge someone as weak-willed when they make a change that, "by the standards of a good intender," they should not have made. In this sense, judgments of weakness of will invariably appeal to our own judgments about when it is good or appropriate to make a change of intention. We should nonetheless, Holton suggests, accept this evaluative aspect of judgments of weakness. Indeed, he argues, it is a virtue of his account that it can explain the "stigma" associated with weakness of will.

We might, however, draw a broader and more tolerant conclusion from the changeability view. If weakness of will is simply a propensity to revise one's intentions more readily than other people do, then there is nothing inherently bad about being weak-willed—just as there is nothing inherently good about sticking to one's intentions no matter what.

In certain cases, being weak-willed may make success less likely. Many of life's prizes go to those who are willing to commit to long-term plans and stick to their commitments (think of medical school or retirement accounts), and someone who is weak-willed will be less likely to win these prizes. But, then again, someone whose will is more changeable may be more alive to the more contingent and ephemeral of life's benefits.

The comparison between the weak and the strong will, in this view, is simply a comparison between two forms that human volition can take, neither inherently better than the other. It is not necessarily bad to be "weak-willed," and we should stop speaking as if it is.

Volitional Diversity

This is a philosophical point, but it has practical consequences. Consider addiction. It is well-documented that addiction is a stigmatized condition and that prejudices against people with addictions are entrenched and widespread. This is one area in which a more tolerant attitude toward what we might call "volitional diversity" may be helpful. If we learn to take a more ecumenical view of volitional diversity, then we might learn to take a more understanding view of conditions, like addiction, that involve patterns of choice and intention that can be perplexing to an outside observer.

Reflecting on Language Used

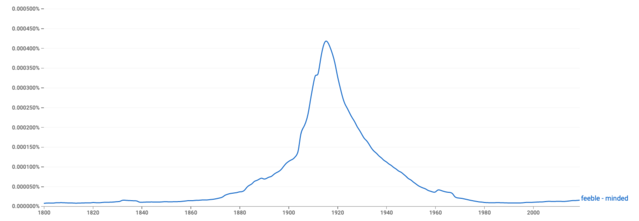

These observations should also lead us to be more reflective about the language that we are using. We have come to recognize that certain terms for describing people's intellectual and volitional lives are intolerable and should be replaced with more descriptive language. Consider the deplorable term "feeble-minded." Though it is scarcely used now, this term enjoyed tremendous popularity, peaking around 1920, before swiftly falling out of favor, as indicated by this Google NGram:

What was wrong with "feeble-minded"? At first pass, this term combined a descriptive claim—that there was something different about certain people's cognitive patterns—with an insulting slur about the people who fit that description. Recognizing this, we retained the descriptive claim while abandoning the slur, so that more accurate terms such as "intellectually disabled" are now favored.

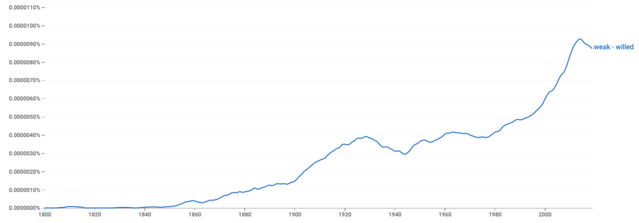

While that term has fallen into disuse, "weak-willed" appears to be peaking, or perhaps has just passed its peak:

Despite its comparative popularity, I want to suggest that the linguistic structure of "weak-willed" is very similar to that of "feeble-minded." It combines a descriptive claim—that there is something distinctive about certain people's volitional tendencies—with a needless and inaccurate denigration of the people who fit that description. It is to be hoped, as the graph above may suggest, that "weak-willed" is now beginning its own slide into obsolescence.

References

Holton, R. (1999). Intention and Weakness of Will. The Journal of Philosophy 96: 241-262.