Intelligence

The Meaning of "Smart"

More than ever, we describe things and people as "smart." But what do we mean?

Posted January 18, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

It is unclear if we live in a particularly smart era, but we clearly live in a particularly "smart" era. That is, the usage of the word "smart" is far more common than ever before. We are told that a new TV show or magazine article is especially "smart," a job is advertised as seeking "smart" candidates, people say that one of the things they love most about their partner is how "smart" they are.

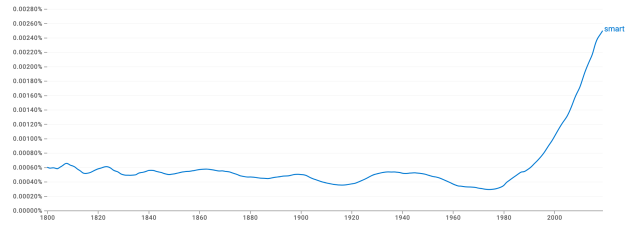

These anecdotal data are borne out by large scale Google NGram data:

This picture displays "smart" plugging along for about two centuries as a relatively uncommon (but not rare) word, and then beginning an upward trend around 1980. It is now about 6 times more common in written language than it was a few decades ago and, as the graph indicates, the trend shows little sign of abating.

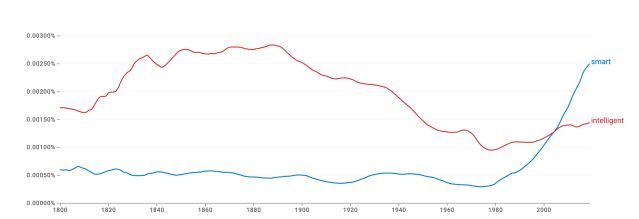

What explains this linguistic change? One thought is that we have become more fixated, as a society, with intelligence, and that "smart" is our handiest word for talking about it. There is some plausibility to this; the computer age has rendered intelligence much more salient and perhaps more prestigious than it was in earlier times. But we actually don't see this tendency in the language:

Covering the same period, this graph shows that "intelligent" has varied over the years but is now about exactly as common as it was in 1800. In fact, for most of the last two centuries, "smart" was a less-common word than "intelligent." Now it is almost twice as common. This suggests that our new obsession is not with being intelligent, but with being "smart." So what does "smart" mean?

One simple hypothesis, suggested by most dictionaries, is that "smart" just means "intelligent" (or, perhaps, having a certain kind of nimble or effortless intelligence). But this hypothesis runs into a couple of problems. First, we have seen that the rise of "smart" far outstrips that of "intelligent," suggesting that something else is at work. Second, reflection on what people mean when they say they are looking for something or someone "smart" belies this hypothesis. We do after all have rough and ready methods of estimating intelligence, such as IQ tests, but these are not quite what the ordinary usage of "smart" seems to convey. When someone says that a new television show is "smart," she is typically not expressing, or not only expressing, that it is the product of someone with an atypically high IQ.

To think more deeply about the meaning of "smart," we need to move away from dictionaries and reflect on the role of evaluative language more broadly. The philosopher Bernard Williams introduced the idea of "thick concepts." The thickness of these concepts or terms lies in the fact that they serve not only to describe the world, but also to express evaluations of it.

Consider a word like "courage." Let us say that someone jumps into a dangerous ocean to save a drowning child. When we say this act showed "courage," we are plausibly saying at least two things: First, that the act demonstrated a certain degree of tolerance of risk or danger. Second, that the act is praiseworthy, in part for this reason. If someone jumps into a dangerous ocean for no reason at all, or for entertainment, she is also demonstrating a tolerance of risk or danger. But her act is not courageous, for there is nothing praiseworthy about it. "Courage" concerns not only what happened, but also our attitude toward it.

I suggest that "smart" is a lot like this. When we describe a person or act as "smart," we are saying at least two things: First, that the person or act displays some degree of intelligence. But this is not all. The other aspect of "smart" is an evaluative one. It says, roughly, that this display of intelligence is one that the speaker considers praiseworthy, or which accords with the speaker's values. If there is a cleverly worded advertisement in favor of a political cause that I support, or a thoughtfully posed objection that supports my point of view, that is "smart." But if there is a cleverly worded advertisement in support of my political opponent, or an objection which undermines my favored theory, that is not smart at all.

This account of the meaning of "smart," if it is on the right track, encourages a degree of caution. Thick concepts are notorious for the way they build evaluative views into purportedly neutral language. Consider "chaste." This term has a certain descriptive content to it, but it also tacitly accepts a certain view of gender and sexual morality, one which many of us would now reject. We are therefore rightly reluctant to describe people as "chaste," and I think we should show a measure of reluctance toward "smart" as well, which is not as descriptive as it seems to be. To refrain from using "smart" is to embrace a certain humility, a certain distance from our own evaluations.

A similar point applies to those who aspire to ask "smart" questions or to pursue "smart" plans. This looks like a goal of being intelligent in thought and action. But if the foregoing is right, it is inevitably something other than that: a goal of being intelligent in thought and action, but in that certain way that is approved of by one's audience. This is a goal that one generally satisfies only by displaying both intelligence and a certain measure of conformity. Similarly, someone looking to hire "smart" employees, or to read "smart" articles, will often be seeking out people or writing which, among other things, confirm her own worldview. It may be that, if we are interested in pursuing and supporting intelligence in all its variety, we should be a little less concerned with being "smart."

References

Bernard Williams. 1986. Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Harvard University Press.