Psychiatry

Who Is "High-Functioning"?

The "high-functioning" label is ever more common. What does it even mean?

Updated April 5, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- "High-functioning" is not itself a psychiatric diagnosis or a part of one.

- One possible reason for the rise the term's use is a tendency toward more open discussions of mental health.

- Another reason may be the ever-increasing demand to be "busy" or to "hustle."

Many psychiatric diagnoses are sometimes amended with the curious adjective "high-functioning." Thus, someone may identify themselves (or someone else), as a "high-functioning" alcoholic, or as having "high-functioning" autism, or as having "high-functioning" depression. It is worth asking what this term is supposed to mean and why we find ourselves invoking it so often.

To begin, "high-functioning" is not itself a psychiatric diagnosis or a part of one. No psychiatrist or other mental health professional will diagnose a person as "high-functioning," whether or not she also meets criteria for some other mental health disorder. If anything, psychiatric diagnoses tend to imply a failure of function: Part of the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders, or for mood disorders, involves some impairment in work or relationships. The province of mental health professionals is in the first place low functioning and its potential causes. "High-functioning" is a label that people choose for themselves.

What Does "High-Functioning Mean?

What does this label mean? At first approximation, it cancels certain aspects of the label to which it is affixed. An alcoholic may have difficulty maintaining regular employment—but a "high-functioning alcoholic" may have a high-paying job. A person with autism may have difficulty in school—but a person with "high-functioning autism" may attend an elite university. And so on. "High-functioning" seems to block certain implications that might be drawn about a person because of a psychiatric label and to imply that the person is in a certain respect different from the people who generally carry that label.

Put that way, "high-functioning" sounds like it is a point of pride. But it is not quite that. I have never heard a person proudly describe themselves as "high-functioning." The label is used with a measure of embarrassment, in something like the same way that people confess to being "perfectionists" or being "type A." There is an air of self-criticism to the term "high-functioning," but also, for lack of a better word, an air of the humblebrag.

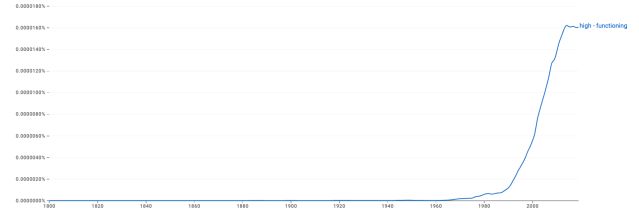

But I am less interested in the question of how individual people deploy this term to describe themselves than I am in what the rise of this term signals about our culture of mental health more generally. The rise of this term is borne out by Google data:

How has this term, once a rare academic neologism, become so much a part of our talk about ourselves? I want to suggest the hypothesis that the rise of "high-functioning" is a product of two broader tendencies.

Why Is the Term "High-Functioning" Being Used More?

One is an admirable tendency toward more open discussions of mental health, and especially of one's own mental health challenges. It is no secret that people now are more open than ever in discussing—with friends, in the workplace, and on social media—their mental health. And this tendency is a good one, a slow turning toward disclosure, openness, and mutual empathy.

Another tendency is the ever-increasing demand to be "busy" or to "hustle." If leisure was once a sign of status, in many contemporary cultures, something like the opposite is true today. What is important is to constantly be doing something—making money, ideally, but if not then some other form of industry. Again, this demand makes a kind of sense: It is a good thing to find oneself fully occupied with useful work, even if this demand has come to take on, in recent years, an especially frenetic air.

I think the secret, or perhaps not-so-secret, appeal of "high-functioning" is that it allows us to meet these twin demands. To label oneself a "high-functioning alcoholic" or a "high-functioning depressive" is to satisfy the demands of both self-revelation and industry. Someone who calls herself a "high-functioning X" is someone who is open about her mental health challenges (she has disclosed that she is X) and who is also meeting or exceeding contemporary expectations with regard to productivity (she is functioning highly, by her own admission).

None of this, I want to insist, is inherently objectionable. Someone who is both honest about her mental health challenges and who is achieving important goals is someone to be admired, at least in many cases. But I think it curious that this has become so common a self-description and perhaps, in some cases, a certain kind of ideal.

It is worth contrasting another traditional ideal—the person who has perfectly good mental health but doesn't do much of anything at all, something like Bertie Wooster in P.G. Wodehouse's novels. This ideal is problematic as well, but it is worth reminding ourselves that it is at least one form that a happy life may take and that it is precisely the opposite of the one encouraged by talk of "high-functioning." Amid the rise of "high-functioning" talk, it is worth recalling the possibility of, as it were, passably functioning joy.