Animal Behavior

The 3 Laws of Minded Behavior

This scientific framing explores the core forces that shape animal behavior.

Updated November 23, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- A frame for organizing animal behavior into three laws has been proposed.

- The first law relates to the allocation of activity based on options in the current situation.

- The second law relates to the evolutionary history of the species.

- The third law relates to the learning history of the specific animal.

Recently, I came across a helpful article by William Baum (2018)1 on the “three laws of behavior.” Baum is a behavior analyst who works in the tradition of B. F. Skinner, and the article focuses on the core “forces” that drive operant behavior.

Operant behavior is the behavior of the whole animal operating on or in its environment. The “operant” refers to the feedback between the animal and the environment that influences or selects the pattern of behavior going forward. For example, if a pigeon pecks on a key and receives a food pellet and then increases that behavioral response, the operant is the consequence of the behavior that increases the likelihood that it will happen again in similar situations (i.e., it is a positive reinforcer of that behavior).

In the paper, Baum tries to get to the core forces or functions that shape behavior. The three laws he identifies are 1) the Law of Allocation, 2) the Law of Induction, and 3) the Law of Covariance. The Law of Allocation refers to how actions are a function of time and alternatives. The idea here is that to be alive is to be an investing organism, and animals allocate their investments of time and energy based on the options, and they attempt to match their investments to maximize the rate of return, framed by levels of reinforcement and punishment or costs relative to the various possible paths of investment available to them.

The Law of Induction refers to where the basic drives of an animal come from. To frame this domain, Baum introduces the concept of "phylogenetically important events" or PIEs. Phylogeny refers to the evolutionary history of the species. The concept of induction emerges from the history of behavior analysis and how it came to incorporate evolutionary forces in understanding how animals were predisposed toward certain investments.

The Law of Covariance refers to the animal’s developmental history and experience. Basically, what the animal has learned is paired with how the animal is working from that history to predict the best outcome for the future.

So, the basic laws of behavior are that an animal allocates its time and energy based on the options it faces and attempts to maximize its return on investment relative to the options. Animals are driven toward outcomes that were shaped by evolutionarily important events and patterns associated with survival and reproduction. Animals learn to adjust their investments based on elements that covaried with past events, both in terms of the associations and consequences that enable animals to predict outcomes. I think this is a helpful framework for understanding the core of animal behavior. The main critique I have of the article is a critique I have of behavior analysis in general, which is that the school of thought fails to effectively frame “behavior.”

I have developed a framework that allows us to bridge behavior analysis with cognitive science into a coherent understanding. This is accomplished via a new system of understanding called UTOK, which stands for the Unified Theory of Knowledge (Henriques, 2022)2. UTOK provides us with a new way to understand mind and behavior. It makes clear why we should consider the “whole behavior” of animals, which is the frame Baum uses, as a particular kind of behavior. Specifically, the behavior of the animal as a whole should be considered minded behavior.

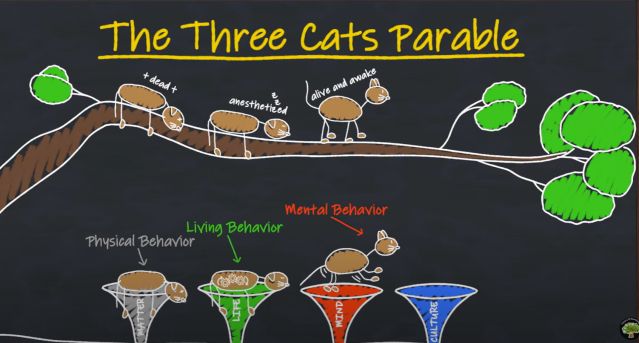

The concept of minded behavior can be framed by UTOK's "parable of three cats falling from a tree." Imagine three cats that fall from a tree. The first cat is dead. When it falls from the tree, it behaves as a material object, and things like gravity, its mass, and air resistance determine how it behaves. The second cat is alive but anesthetized. It falls just like the first cat. However, if we look inside this cat, we see that it is behaving as a living organism. Cells are metabolizing energy, the blood is flowing, etc. Finally, the third cat is awake. It lands on its feet and takes off. This is mental behavior or the behavior of a minded animal. Mindedness refers to how animals behave via a sensory-motor loop to act on their environment.

This framework is consistent with recent work in cognitive science that suggests that we should think of "the mind" as being extended into the world. The concept of mindedness as the property of whole animals acting on and in their environment helps bridge the behaviorist perspective with the 4e cognitive science perspective. To make this point clear, consider this quote by Skinner in his essay, Whatever Happened to the Science of Behavior? (1987, p. 784):

Cognitive psychologists like to say that “the mind is what the brain does,” but surely the rest of the body plays a part. The mind is what the body does. It is what the person does. In other words it is behavior, and that is what behaviorists have been saying for more than half a century.

This quotation from Skinner shows that, in many ways, both behaviorists and cognitivists are actually referring to the same thing. If you are wondering whether this has any real-world implications, consider this recent Psychology Today blog by a psychiatrist commenting on how the concepts of behavioral and mental health both overlap but also mean different things to different people.

UTOK helps us make sense of the confusion. It gives us a map of reality and science called the Tree of Knowledge (ToK) System that depicts the universe from a scientific perspective as an evolving wave of complexification that moves from energy information to material objects to living organisms to minded animals to cultured persons. The ToK System defines the Mind as the set of minded behaviors by animals. UTOK’s Behavioral Investment Theory3 provides the metatheoretical framework for understanding minded behavior patterns of animals in a way that is highly consistent with Baum. The point is that these three laws allow us to frame minded behavior as a function of time and energy allocation shaped by evolution and the learning history.

References

1. Baum, W. (2018). The three laws of behavior: Allocation, induction, and covariance. Behavior Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, Vol. 18, No. 3, 239–251.

2. Henriques, G. (2022). A new synthesis for solving the problem of psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave Macmillian.

3. Henriques, G. R. (2022). Behavioral Investment Theory: A metatheory of Mind1. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 321-355). Palgrave Macmillan.