Philosophy

What Is Big History and Why Does It Matter?

Big history tells the story of how we came to be.

Posted December 8, 2023 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Big History is an interdisciplinary approach to understanding humans across time and complexity.

- A new map of Big History has recently been proposed.

- It divides the evolution of complexity into four dimensions of Matter, Life, Mind, and Culture.

My father is a professional historian who specializes in the Founding Fathers, especially George Washington. I recall a conversation I had with him, perhaps when I was an undergraduate, when I asked him about when “history” starts. He told me that the profession of history is deeply connected to writing, and the scope of history as an academic discipline goes back about 5,000 years. Going farther back in time, you get into archeology and paleontology, and the period is often described as “pre-history.” Of course, when you think about it, it actually is kind of a misnomer. After all, whatever came before “history” was just the history that led up to that point.

The idea that expands our conception of history into the deep past and frames it as a continuity with our species prior to civilization and into our long evolutionary and cosmic past is called Big History. It is an interdisciplinary perspective that brings together natural scientists, social scientists, historians, and educators to help people understand the long arc of change and development that gave rise to us.

David Christian is the world historian who started the movement back in the 1980s. He developed a Great Course on Big History that Bill Gates took, and Gates was so impressed by the course and its implications that he donated a million dollars to the movement. There is now a journal, an association, and many books and courses that are offered in the name of Big History.

Big history is about placing ourselves in relationship to the universe on the dimensions of time and complexity. With Big History, we can go back to the “big beginning” at the Big Bang, which our best estimates say took place approximately 13.8 billion years ago. From there we can map increasing stages of complexity.

When Big History got started, David Christian identified eight different “thresholds” of complexity that have been crossed that ultimately get us to the modern era. These are: 1) the Big Bang and the origins of the material universe; 2) the first stars and galaxies; 3) chemical elements; 4) the earth and solar system; 5) life on earth; 6) human culture; 7) agriculture; and 8) the modern industrial revolution.

A New Map: Toward a Big History 2.0

The eight thresholds are a useful way to frame the evolution of complexity for educational purposes because they identify many of the key domains of study. However, in the lead-off paper in the most recent issue of the Journal of Big History1, my colleague Tyler Volk and I argued that the thresholds were not the most accurate or effective way to map cosmic evolution. We proposed a new map of Big History. The Big History 2.0 model that we outline in our article emphasizes five points that shift the map from the old version to a new and better way to understand our history and define key concepts and their interrelations.

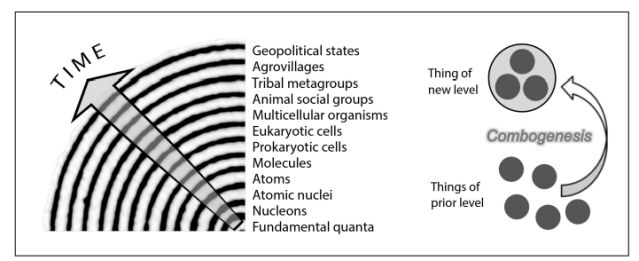

First, we recommended an explicit shift from the emergence of complexity in general to what Tyler Volk, in his book, Quarks to Culture: How We Came to Be, called “combogenesis.” This is the layering of complexification that tracks our specific pathway. Combogenesis is when parts come together to form new wholes. So, particles forming atoms is an example, as are molecules forming cells or cells being grouped into multi-cellular organisms. This process is different than general patterns that emerge at a larger scale. So, the formation of the solar system or galaxies are not examples of combogenesis.

This difference gives rise to our second point, which is that there should be an explicit difference made between emergence that is characterized by combogenetic, part into whole leveling from other emergences that arise from aggregate patterns.

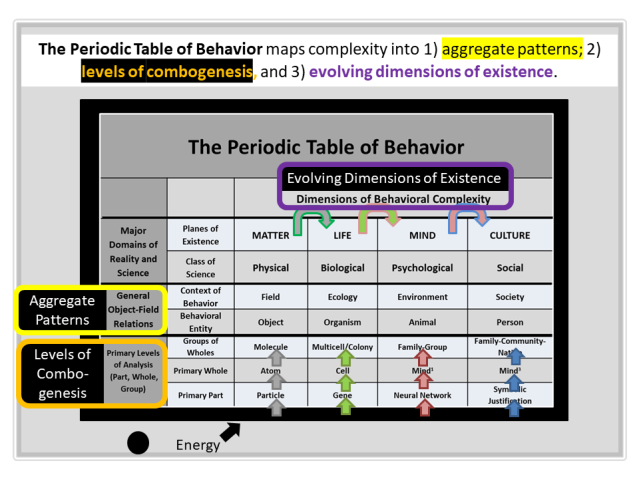

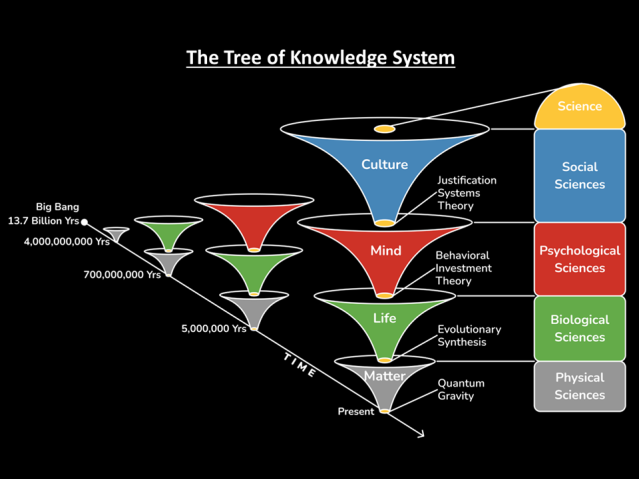

Third, we argued that there was a difference between emergence that characterizes levels versus emergence that characterizes entire new realms of existence formed by new evolutionary dynamics and containing multiple levels. The difference here is between the combogenesis leveling up that takes place from atoms to molecules, for example, which happens within the Matter dimension of complexification, and what happens when we move from Matter to Life, which we frame as a whole new realm or plane or dimension. The logic of this difference is seen clearly in our new map of Big History called the Tree of Knowledge System, which is depicted at the end of this blog.

Fourth, this means there are at least three different kinds of emergent patterns of complexity: 1) aggregate forms like solar systems and galaxies; 2) levels of combogenesis that happen within dimensions (i.e., atoms to molecules); and 3) evolutionary processes that generate whole new dimensions (i.e., from Matter to Life). We pointed out that these three different kinds of emergent complexity are captured by Henriques’ Periodic Table of Behaviors2 in nature.

Finally, we argued that the old Big History threshold formulation was missing a major realm or dimension of complexification: that of Mind, or the Mind-Animal plane of existence. The Tree of Knowledge System provides the vision logic for why minded animals are appropriately considered a specific realm, which is generated by evolutionary and developmental dynamics and is constituted by a novel information processing system (i.e., the brain and nervous system).

In conclusion, Big History is a powerful and useful way to see ourselves as part of the cosmos, and David Christian should be commended for launching this interdisciplinary effort. The eight thresholds are useful for pedagogical purposes. However, the time is right for us to update the model and utilize a more refined analysis of the kinds of complexity we see and, in particular, the kinds of complexification processes that led to us (i.e., processes of combogenesis that evolved from material objects into living organisms into minded animals and, finally, cultured persons). With a new map of Big History 2.0, we will really be able to connect the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities into a coherent, holistic picture in the decades to come.

References

1. Henriques, G, & Volk, T. (2023). Toward a Big History 2.0. The Journal of Big History, 6(3), pp. 1-4.

2. Henriques, G. R. (2022). The Periodic Table of Behavior: Mapping the levels and dimensions in nature. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 253-284). Palgrave Macmillan.