Cognition

The Mind vs. Layers of Mindedness

Shift your thinking from "the mind" to layers of mindedness.

Posted January 11, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- We should shift our language from talking about "the mind" to talking about mindedness.

- Mindedness describes a set of principles and processes.

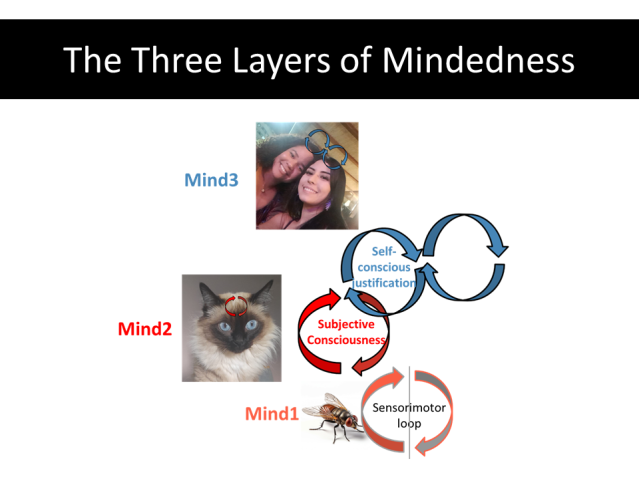

- Layers of mindedness are the sensorimotor loop, subjective conscious experience, and self-conscious reasoning.

Let's consider the question, "What is the mind, and how does it fit into the material world?"

For most people, the mind is a source inside of us that empowers us to be aware, to understand, to think, and to reason. It is also the fount of our feelings, perceptions, and intuitions. For many religious folks, it is given to us by God; we are ensouled by Him via the mind.

Clearly, then, the mind is a beautiful thing. But, as we appreciate its beauty, we also realize its puzzle. The mind seems so different than the rest of the material world that it is hard—I mean really hard—to understand how the two are related. It is so hard that it remains one of the central problems in modern philosophy. Consider that René Descartes, who is often considered the father of modern philosophy, famously divided the world into two domains—the material world (called res extensa) and the mental world (res cogitans). Splitting the world this way is called “substance dualism.” Although it seems to make sense, it turns out that this is not a very good solution. The reason is because it is impossible to see how the world of the mental could influence the material world if it were a totally different substance.

Very few modern philosophers are substance dualists. Most are physicalists, and they think that the mind is, ultimately, a material substance. Many consider the mind as a kind of computational device, kind of like a computer, only done by brains. This is a useful frame, but it is also one that I find to be limited and potentially misleading. The goal of this post is to invite you to shift your thinking about “the mind.”

Mindedness

When we say “the mind,” we are indexing it as if it were a thing, an entity in the world, that is made up of a particular substance. But this might not be the best way to go. In my work on the Unified Theory of Knowledge (UTOK),1 I have reframed the concept as "mindedness." Mindedness treats the concept more like a verb or an adjective that describes a set of processes and properties. Before I get into what those processes and properties are, it is useful to point out that a similar shift happened more than a century ago with the concept of life.

Consider the question, “What is ‘the life,’ and how does it relate to the material world?" This probably sounds odd to you. The reason is because we no longer think about “the life” as some substance that mysteriously acts on dead matter to bring it alive. Instead, life is a term that describes a set of properties and processes. That is, life is a concept that describes the way matter is arranged in living entities. It refers to the set of structural and functional relations we see in those organisms. For example, living things are things that consume and metabolize energy, grow, reproduce, and respond in a functional way to the environment.

The shift from the mind to mindedness suggests a similar move. Mindedness does not refer to a substance but to a set of functional processes embedded in a particular structure.

The Sensorimotor Loop

What is the set of structural and functional processes that the word mindedness describes? According to UTOK, the core of the structure of mindedness is the sensorimotor loop in animals with brains and complex active bodies. The core functional patterning refers to the patterns of awareness and responsivity that such animals exhibit. Mindedness, then, is the set of properties and processes associated with the sensorimotor loop in animals that allows them to demonstrate functional awareness and responsivity in the world.

When you carefully sneak up on a housefly to swat it with your fly swatter, you are demonstrating awareness of the mindedness of the housefly. That is, you know from experience that if the housefly senses you, it will fly away. That is mindedness in action.

As you consider this example, there are likely many different thoughts running through your mind. Perhaps you find it interesting to consider a housefly as a “minded animal” because it has a sensorimotor loop that allows it to avoid your flyswatter. However, you are probably also thinking that the actions of a fly seem a long way away from what you think about when you think of the mind.

As you have such thoughts, it seems likely that inner experience itself is a good place to start to frame the mind. This is the world of subjective consciousness: feeling pain, wondering about the future, remembering the past, having a sense of self. Does a fly have those "things"? Who knows. However, we can be pretty confident that an animal like a cat has inner experiences. How does subject-conscious experience arise in creatures like cats? This is one of the central questions in neuroscience and psychology. Although it remains a bit of a mystery, a good starting point is that the inner mind's eye emerges as a kind of second-order loop on top of the basic sensorimotor loop that frames the first layer of mindedness. This is the way a whole class of models in consciousness research frame consciousness. They are called "H.O.T." models, which stands for "higher order thought." In other words, there is a nonconscious loop first, and then consciousness emerges as a higher-order loop on that loop.

For now, let's frame subjective conscious experiences as inner loops of mindedness. If we call the first loop of mindedness Mind1, then we can frame this second loop as Mind2. This is the inner world of subjective conscious experiences that emerges as a higher order of recursive process on the more basic layer of mindedness.

This is progress, but we still haven’t gotten to the kind of mind that René Descartes was considering. That is, we have not considered the processes associated with human reasoning, self-conscious reflection, and rationality. This domain is well-captured in Descartes' famous line, “I think, therefore I am.”

According to UTOK, it is indeed the case that humans have a different kind of mindedness. We can call this the domain of Mind3. This is the world of propositional language, questions and answers, and systems of justification that make human mindedness so different from the mindedness of other animals. Where does this come from? Well, one good answer is that it emerges in the "intersubjective language space" between subjects. And what are "subjects" in this model? A good answer is given by the domain of Mind2. If so, we can think of Mind3 as an intersubjective language loop on the domain of Mind2. This gives us three layers of mindedness as shown in the diagram below.

To conclude, next time you are thinking about the mind, shift from thinking of it as a substance into thinking of it as a set of processes and properties. From there, look to frame these properties and processes via three loops. The first is the sensorimotor loop that allows animals to act in the world, and we can call that Mind1. The second is an inner loop that gives higher animals and humans an inner mind’s eye, or subjective conscious experience, and we can call this Mind2. And the third is the domain of self-conscious reflection and justification, formed by intersubjective language systems, which we call Mind3. These loops are the three layers of mindedness. And, if you are still keen on talking about “the mind” as the source or force or thing that consists of your actions, feelings, and narrative reflections, at least you now have a way of framing the mind in a way that is consistent with science.

References

1. Henriques, G. (2022). A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave MacMillan.