Consciousness

Seeing Mindedness Everywhere

Mindedness is a new concept linking mind and behavior in a coherent picture.

Posted February 1, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Mindedness is a new way of framing mind.

- It refers to the properties associated with animal behavior.

- Mindedness is everywhere when you know how to look for it.

“How was your appointment, Dad?” I asked, as he came home from the doctor’s office.

“Fine,” he said. “Except now I am seeing mindedness everywhere! I saw it in the birds, and in the cat that crossed the street. I even saw it in this video on insects! Mindedness is everywhere when you know how to look for it!”

“Sweet,” I replied. “And I am enjoying seeing your minded behavior right now.”

This was a gratifying exchange for me. I have not always had huge success explaining UTOK, the Unified Theory of Knowledge,1 to my dad. As a retired history professor, he is certainly a bright, educated man. We have even worked together on some scholarly pieces that use it. For example, he is a George Washington scholar, and we co-authored this post on how to understand George Washington’s personality from the vantage point of UTOK. However, trying to get him to see how UTOK frames “the mind” has not been easy.

The day before, I had been on a walk with my parents around a pond, and we heard lots of bird calls. I said, “Cool to listen to those minded animals!”

My dad then paused and asked what I meant.

“Mindedness refers to the properties of animal behavior that make their behavior so unique," I said. "Specifically, it refers to the sensorimotor loop in animals that shows up in how they functionally respond to the world. So, we are hearing them engage in communication with each other. That communication is a kind of functional awareness and responsivity. That minded behavior pattern flows through their complex active bodies, and especially their brains.”

“I don’t know if birds are conscious about what they are doing, so I don’t know if they have minds like that,” he replied.

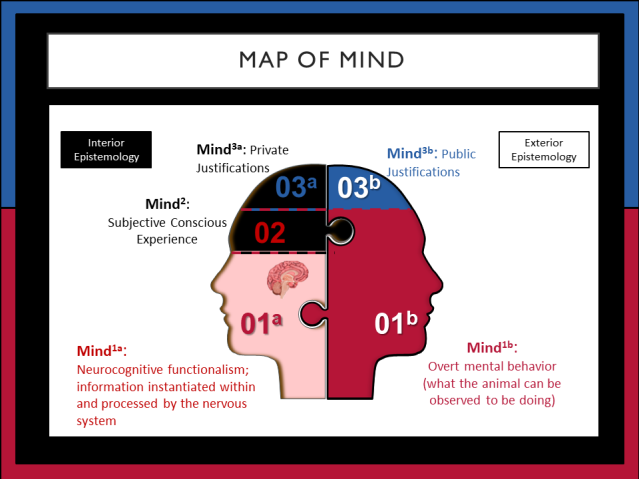

“As we have talked about this before, through UTOK, I define ‘mind’ differently than you do.2 You think of it as the self-conscious reasoning part of your existence that enables you to be aware of who you are and say why you do what you do. For example, you connect your mind to how you understand this conversation. In UTOK, that domain of mentation is called Mind3. It is a specific kind of mental process. However, there are other mental processes.”

“Right," he now recalled. "I keep forgetting that you have different categories of mind. There are three, right?”

“Exactly. You can think of the first, which is called Mind1, as referring to animal behavior that flows through brain activity. It has to do with the functional awareness and responsivity of animals, that is the behavior part, and how that emerges, which is primarily through the brain.”

“OK. That one is still kind of weird to call mind.”

“I know. It takes some getting used to. You can think of Mind1 as the brain-behavior definition of mind. So, when you watch animals behave, you are seeing mindedness or minded behavior.”

“The second meaning of mind—um, Mind2—that was feelings, right?” he asked.

“Basically, yes. Technically, Mind2 is called ‘subjective conscious experience,’ and it refers to experiencing the world from the inside out. To make it personal to you, it refers to your inner experience, your 'mind’s eye' from the inside. It is your conscious experience of being that comes online when you wake up, goes offline when you sleep, and flickers on and off when you dream.”

“How does that happen? I mean, how does the brain, or I guess in your language, the domain of Mind1, give rise to Mind2?”

“That, my dear father, is a great question. That is called the ‘hard problem of consciousness.’ Let’s not go down that rabbit hole, as we are getting near the end of our walk.”

“OK. And then there is Mind3. That is us talking, right?”

“Yep.”

“And you are saying I can see mindedness in the birds because of the way they are acting in the environment?”

“Yep. Indeed, whenever you watch an animal ‘do something,’ you are watching minded behavior. Look over here,” I pointed. “See this little bug crawling on this flower? That bug walking is a kind of minded behavior. It arises from its brain and complex active body, and it produces a functional effect on the environment.”

“Well, yes, but that is what animals do.”

“Exactly!”

“But how do I know if they have minds?”

“Dad, you are looking at it! Mindedness is seen in the functional behavior, not somewhere else behind it," I explained. "Look at the tree. Is it alive?”

“Of course.”

“So, you are seeing living behavior, right? You don’t need to wonder if there is some ‘life force’ behind that behavior. The behavior is living.”

“Sure.”

“Well, that is what I am saying about mind. You are watching minded behavior. Notice how different insects, squirrels, and birds behave relative to the flowers and the trees. You see that they behave very differently, right?

“Obviously.”

“Well, that is it. That is minded behavior or mindedness. It is right in front of you!”

“OK, well, that is obvious.”

“Well, sort of. It is obvious in the sense that, if you know how to look for it, you can’t unsee it. The interesting thing is that our culture got confused about what mind is and lost the ability to see it. So, in that sense, it is not obvious at all. In fact, that is why we are talking about it, and I am trying hard to get you to see it that way.”

“So you are basically saying that all the animal behavior I see is minded behavior.”

“Yes.”

“Well, that is everywhere.”

“Yep.”

“OK, well, I think I understand a little bit better what you are saying. It is just that you use words in weird ways that make your ideas so confusing.”

“I hear you. As I have told you before, it is not my goal to confuse people. What I am doing is developing a new grammar for how to understand the world, and to do that, we need to rethink some keywords, like mind, consciousness, and behavior.”

And the following day he was seeing mindedness everywhere he looked.

References

1. Henriques, G. (2022). A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave MacMillan.

2. Henriques, G. R. (2022). Mental behaviors and the Map of Mind. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 287–319). Palgrave Macmillan.