How Loving Relationships Change Us for Good

Loving relationships take work, but caring for your partner and highlighting shared sources of strength will help you form a deeper connection, recasting the arithmetic of "1 + 1."

By Psychology Today Contributors published November 2, 2021 - last reviewed on November 7, 2021

Together In We-Ness

How to foster a healthy sense of “us."

By Scott Stanley, Ph.D.

The Bible describes how Adam and Eve will be “united and become one flesh.” Although that line is preeminently describing the physical union, the passage resonates because of the implication of a deeper bond. Aristotle wrote, “Love is composed of a single soul inhabiting two bodies.” This goes further than two becoming one. The initial version of human beings was a threat to the gods, so Zeus had them split in two. The half-not-whole beings were consigned to spend their days searching for their other half.

These ancient thoughts hover around the nature of individuality and oneness, but the nuances and traditions around them are different in how they relate to views of mating, love, and marriage. In one view, two identities were intentionally created with the idea that they would seek to be one in core aspects of life. In the other, one entity was split into two for the express purpose of inflicting a weakness. There are doubtless many variations of these ideas in every culture that has ever existed.

As these and other themes suggest, there is a fundamental human drive to seek and be in a relationship that has this quality of “us.” To join with another. Beyond this central fact, there are healthy and less healthy views of what “becoming us” can be like.

What Is "We-ness"?

The term we-ness has been around for a while, but well after Aristotle. It denotes a relationship where two people have formed a depth of connection that supports a sense of shared identity.

Supporting ideas consistently come up in relationship commitment literature. Harold Kelley and John Thibaut described how two partners who were growing in interdependence would move from having only individual goals to developing a view of the future based on joint outcomes. They called this “transformation of motivation.” Although they almost never used the word commitment, what they were describing was the psychological formation of it.

Similarly, George Levinger noted that ‘‘as interpersonal involvement deepens, one’s partner’s satisfactions and dissatisfactions become more and more identified with one’s own.” Social exchange theorists, such as Karen Cook and Robert Emerson, discussed how the “transformation” from me to we changes a relationship from an exchange market where two individuals were competitors to a noncompetitive relationship that can maximize joint outcomes. One is no longer seeking solely individual gains from the other, but something for us as a team.

I came to view commitment between two partners as the condition where there has emerged a strong sense of “us with a future.”

One of the most influential scholars in the field of commitment was Caryl Rusbult, who, along with her many colleagues, framed and refined a theory of interdependence. Her early work focused on how commitment developed in relationships, with increasing mutual investments, curtailing attention to alternatives, and a deepening desire for a future with the partner. I first noticed the term we-ness in work done by Rusbult and colleagues. They used the term in contrasting friendships and romantic relationships, suggesting that because sexuality was in play in the latter, there was a stronger possibility of two individuals merging into one in a way that fostered we-ness. Not that far from the ideas of the ancients.

Couple identity is the degree to which an individual thinks of the relationship as a team, in contrast to viewing it as two separate individuals, each trying to maximize individual gains. In trying to assess whether or not a person has a sense of a shared identity with a partner, I developed a set of measures to assess commitment in romantic relationships, dividing the world into the broad themes of dedication and constraint. For example:

I like to think of my partner and me more in terms of “us” and “we” than “me” and “him, her.”

Or, in the reverse:

I want to keep the plans for my life somewhat separate from my partner’s plans for life.

If a relationship is safe and healthy, we-ness is good. Yet there is a dark side: enmeshment. This implies the obliteration of one or both identities in some manner.

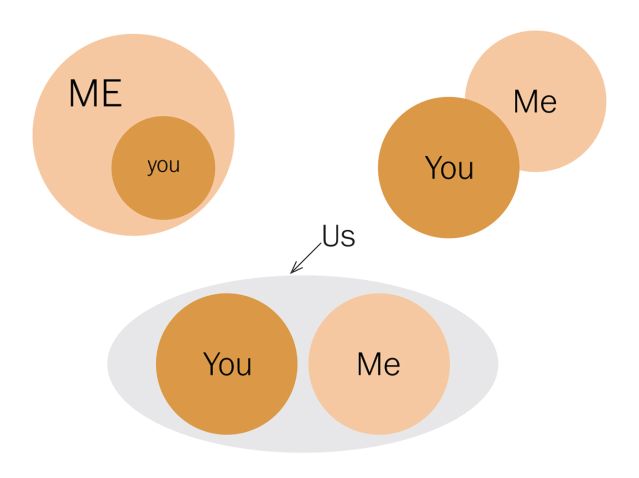

In some relationships, there is a painful reality (see below illustration) with one partner wanting more and the other preferring or only capable of less. Those are situations where one partner is substantially less committed than the other and likely a lot less willing to have, develop, or nurture that third identity.

Although there is no data that I know of that could directly test this, it seems evident that modernity has fostered ever greater levels of individualism. It is not hard to posit that this complicates the development of relationships characterized by having a shared, couple identity. Yet this is true in the same era in which we also see an emergence, or re-emergence, of a desire for a relationship of a sort described in a famous line from the movie Jerry Maguire: “You complete me.” Aristotelian elevator talk, really. That’s not just you and me developing a sense of us; that third identity is “I am not whole without you.”

All these ideas touch on the concept of soulmates. There are versions of this idea that are appealing, but it has two problems. First, it implies that there is one perfect match out there for each person. Second, it supports the illusion that finding that person would make love and marriage blissful. But that search becomes formidable, and there are negative effects of holding expectations that your soulmate will complete you in only the most wonderful way. That might be the resolution of the paradox of a growing individualism overlapping with a growing desire to find one’s soulmate. It would take a relationship with astounding gravity to overcome the escape velocity fueled by individualism.

There is a healthy idea of we-ness that does not imply either enmeshment or finding perfection in a partner. Not everyone wants we-ness. But, for those who do want us in their life, they will have to look for a relationship with the right balance of me and we and then invest in protecting it. Two perfect partners rarely join as one, but two imperfect partners can get pretty far in life if they nurture the sense of “us with a future.” n

Scott Stanley, Ph.D., a research professor and a co-director of the Center for Marital and Family Studies at the University of Denver, is the author of Fighting for Your Marriage.

Top left: In one of many possible depictions of enmeshment, one person’s identity is absorbed into the other. Top right: Two lives are connected but without having developed an identity of us—or at least, not yet. Bottom: A healthy sense of us still retains a clear understanding that there are two separate individuals involved. There are three identities: you, me, and us. In a strongly committed relationship, there will be some identity of us, but it will have a boundary.

Does Your Partner Truly Care?

How to gauge responsiveness and sensitivity in your partner.

By Susan Krauss Whitbourne, Ph.D.

You’d like to think that your partner cares about you and is willing and able to respond to all your needs. Yet between work commitments and managing the kids’ remote learning, how much can you count on him or her?

It helps to have a partner who listens to you, takes you seriously, and accepts that at times you may be feeling angry, sad, or just plain lousy. According to research by Dev Crasta at the Canandaigua, New York, Department of Veterans Affairs and his colleagues, “Perceived partner responsiveness has emerged as a cornerstone concept in relationship science.” Referring to earlier work by the University of Rochester’s Harry Reis and colleagues, he says this is the process through which you and your partner react in supportive ways to the “central, core defining features of the self.” Responsiveness is now so significant to relationship researchers that it is one of the 14 leading principles in the entire field.

How did perceived partner responsiveness become so important in relationship research? In part, its development can be traced to the body of research conducted by Reis and his collaborators over the years as they sought to understand the factors that contribute to couple satisfaction. Couples with high levels of this responsiveness are more likely to engage in self-disclosure, allow their emotional vulnerability to show, and communicate greater levels of gratitude, trust, and support toward each other. As the research continued, even more impressive evidence was obtained, showing that couples high in responsiveness have lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol when they’re placed under duress. They even live longer.

Crasta found that it is also important to take the related concept of insensitivity into account.

The study authors looked into the idea that if you love your partner, you’re willing to let some of the problems in your relationship slide. If measured properly, perceived partner responsiveness should remove this global evaluative factor and instead provide a pure index of responsiveness and insensitivity.

You can take the test by answering the following 15 items on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 5 (completely). For each statement, you should insert your partner's name into the blank (if you have no partner now, you can substitute a past partner’s name).

How Responsive Is Your Partner?

1 ___ really listens to me.

2 ___ seems interested in what I am thinking and feeling.

3 ___ is understanding.

4 ___ tries to see where I’m coming from.

5 ___ is attentive to my needs.

6 ___ is responsive to my needs.

7 ___ takes my concerns seriously.

8 ___ really gets my point of view.

9 ___ does not accept my feelings and concerns.

10 ___ dismisses my concerns too easily.

11 ___ seems to ignore the things that are most important to me.

12 ___ does not really understand my wants and needs.

13 ___ does not really take my concerns seriously.

14 ___ often really does not hear what I am saying.

15 ___ When I’m feeling worried or stressed about something, it only makes things worse to tell ___ about it.

The first eight items form the responsiveness scale, and the second eight items form the insensitivity scale. The average responsiveness score was slightly over 3.5 with most scores falling between 2.4 and 4.7, and the average insensitivity score was just under 1, with most people scoring between 0 and 2. There were gender differences with men having lower overall scores, but only by a fraction of a point.

As you might expect, perceived responsiveness and insensitivity might wax and wane over the course of even short intervals of time. In general, though, people scoring well on the scale were more likely to be satisfied in their relationship, to feel that their partner was emotionally supportive, and to rate as lower any hostile behaviors by their partner during times of conflict.

Susan Krauss Whitbourne, Ph.D., is a professor emerita at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She is the author of The Search for Fulfillment.

The Underappreciated Sources of Relationship Strength

By Gary Lewandowski Jr., Ph.D.

In a relationship, it’s too easy to fixate on imperfections. Partners may even manufacture problems that don’t exist. But neglecting to credit what’s working is a major blind spot that can undermine a strong connection. To enjoy a healthy relationship, start paying more attention to what is stable, consistent, and comfortable. Those peaceful, drama-free, status-quo moments are easy to forget, but they’re sources of strength. The following are a few pillars of healthy relationships.

- You can be yourself. You and your partner accept each other for who you are; you don’t try to change each other. You can simply be your own authentic person and show your true identity without worrying that your partner will judge you.

- You are BFFs. Romantic relationships that value friendship emphasize emotional support, intimacy, affection, and maintaining a strong bond. They also focus on meeting needs related to caregiving, security, and companionship.

- You feel comfortable and close. You are comfortable sharing feelings, relying on each other, and being emotionally intimate. Even if vulnerability can be challenging at times, you’ve learned to trust your partner and found it brings you closer.

- You are more alike than different. You and your partner have a lot in common, and key areas of similarity may help make your relationship more satisfying. Sure, there are differences, but you are similar in many more ways.

- Your partner makes you a better person. Your partner helps you refine and improve who you are—not by taking charge and telling you how to change but rather by supporting your choices for self-growth.

- You share the power. While partners may have their areas of expertise (one handles lawn care, the other decorating), they often share decision-making, power, and influence in the relationship. When both partners have a say, relationships are stronger and more likely to last.

- The partners are fundamentally good. What do people want in a spouse? Someone who is reliable, warm, kind, fair, trustworthy, and intelligent. Though these traits aren’t flashy, they provide the foundation for a resilient connection.

- You trust each other. We need to be able to rely on our partner, which comes from a sense of trust. We know that our partner always has our best interests in mind and will be there for us when needed. Trust encourages greater commitment, which encourages greater trust.

Gary Lewandowski Jr., Ph.D., a professor at Monmouth University, is the author of Stronger Than You Think.

The Essential Ingredients of a Loving Relationship

No one just shows up for a great relationship; people make it happen together.

By Suzanne B. Phillips, Psy.D.

We know this much: A loving and permanent relationship is what most people want. There are more than 13.5 million self-help books addressing relationships; clearly, many couples want to improve and sustain their love.

Through working with couples in therapy, I have siphoned essential ingredients for loving, long-lasting unions. They may be obvious, basic to your relationship, hiding in plain sight, something you stopped doing, or something you never tried. Consider them against the backdrop of your relationship even in the face of virus variants, economic strain, and uncertainty.

Look at Each Other

It is likely that when you first met your partner, you looked into each other’s eyes as much as you could and in every aspect of your connection. In a culture that demands watching the road, the screen, the phone, the parallel chores, or the kids, the mutual gaze becomes more difficult over the years.

When couples look into each other’s eyes when they say hello or goodbye each day, when they are having that quick cup of coffee, when they are exchanging bags or kids on the soccer field, they affirm an intimate connection. After all, you don’t just gaze into everyone’s eyes.

In terms of negative feelings, it is far more difficult to dismiss or verbally abuse a partner when you are looking at that person when speaking. The exposure to the other’s eyes seems to underscore the connection and mediate the way in which anger is expressed.

Even if couples avert their eyes when arguing, those with a strong relationship often use eye contact to restore the connection.

Catching the eye of a partner while in public affirms the bond and conveys: I love you. Only two more hours to go. Thank God you are here.

Time may be in short supply—but there is always time to look at each other.

Laugh with Each Other

Laughter has been shown to have physical, mental, and interpersonal benefits. The couple who laugh together reduce stress, step over the small stuff, and feel more connected.

Research suggests that a sense of humor is found to be an attractive trait. In particular, women like men who make them laugh and men are attracted to women who “get them.” Both women and men associate a sense of humor with playfulness and the resilience to get past the rough times.

Laughter is integral to intimacy because laughing means risking being emotionally touched by another.

When partners can laugh at themselves and laugh off the other’s mistakes, the relationship is safe for authenticity and forgiveness.

Since they say you can’t really love anybody with whom you never laugh, laughing each day is a boost to love.

Let It Go

All couples argue, fight, disagree, or sometimes wonder what planet the other is on. That said, the best of couples know when to let it go.

They have learned that when people are in their angry reptilian brain, nothing good happens. One or both need to hit the pause button, take the dog out, start cooking. This would open a space to reset their regulation so they can differ without jeopardizing their relationship.

They are not giving up on addressing important differences of opinion. They are letting go of toxic clashes that become so escalated that solutions and mutual decisions can’t be found.

When couples have a strong connection, they are not afraid of the fight and they are not afraid to give up the fight. They don’t equate differences or disagreements with a lack of love, and they don’t have to win to feel loved.

Couples who can let go have learned that once they have made their point, the other needs time and space. They trust that if they let that happen, they open options for considering whether it is a fight worth having, if they need to be right, if there are unexpected solutions, or even if they should reverse their opinions.

They have learned that apologies come in different forms and different ways and that if an apology has to look or sound a certain way, it will be missed.

They have learned that in the hours, days, and years of a relationship, the connection is more important than winning.

They have learned give and take. They have learned when in doubt: Let it go and assume the best of your partner.

Let the Other Know

A young groom shared a story at his wedding. He said that when his friends asked why he was sure that his bride was the one, he answered, “I can probably live with a lot of people, but I can’t live without her.”

Couples in loving and sustaining relationships let each other know just that. They don’t take the other for granted, and they positively affirm their partner in small and big ways. They let the other know that they are friends, find ways to show that each is desired, and make time (even just 10 minutes) to be together.

Loving partners never assume the other no longer needs to know these things—no matter how long they have been together.

Suzanne B. Phillips, Psy.D., the author of Healing Together for Couples, formerly taught at Long Island University.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.