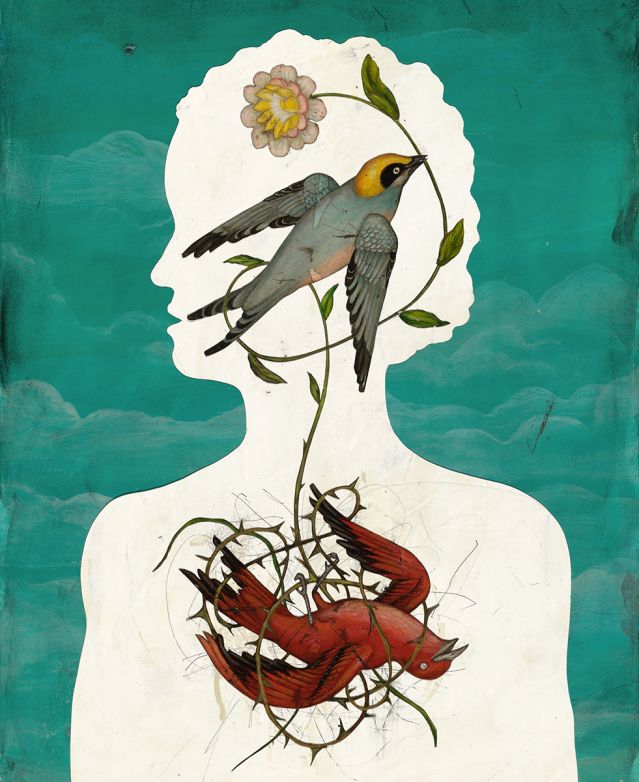

Hearts and Minds

Trauma both causes heart problems and is caused by them.

By Psychology Today Contributors published March 7, 2023 - last reviewed on March 29, 2023

How Trauma Puts the Heart at Risk

A better understanding of how trauma both causes heart problems and is caused by them could help us reduce the risks and limit deadly consequences.

By Thomas Rutledge, Ph.D.

Traumas constitute the most difficult experiences in many people’s lives. Assaults, severe accidents and injuries, natural disasters, life-threatening illness, and the loss of loved ones comprise just some of the most common types of major trauma, and research suggests that at least half of adults will experience one or more major traumas.

While the mental health consequences of trauma and post-traumatic stress have received wide attention, the physical consequences of experiencing trauma are less well-known or invisible to most people. Based on the latest trauma science, however, ignoring the physical consequences of trauma or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) represents a grave error with potentially deadly consequences.

The Cardiovascular Consequences of Trauma

The official—and oversimplified—narrative about trauma and post-traumatic stress is that they represent intense emotional and behavioral responses to life-threatening events. In the diagnostic manual used by mental health professionals, acute stress disorder and PTSD are diagnosed entirely by emotional and behavioral symptoms, such as hypervigilance, anxiety, insomnia, and avoidance of trauma-related situations and stimuli. Yet rapidly evolving neuroscience demonstrates that the underlying pathophysiology of trauma inside the body is equally profound and potentially more harmful, including chronic increases in inflammation, blood pressure, and accelerated biological aging. Among the areas of the body most rapidly and severely affected is the heart.

During a life-threatening experience or event, the brain initiates a systemic biochemical process called the fight-or-flight response. Specifically, the hypothalamus and pituitary and adrenal glands—also known as the HPA axis—coordinate to produce a rapid and powerful stress reaction throughout the body using hormones and neurotransmitters. The latter chemicals markedly alter the normal function of major organs, including the heart.

Although the fight-or-flight response is intended to help a person survive a traumatic event, it can sometimes turn deadly. For example, the incidence of heart attacks and strokes increases substantially during as well as following natural disasters. In fact, deaths resulting from stress-induced cardiovascular events during disasters such as earthquakes can exceed the number of deaths caused by the disaster itself. The number of cardiovascular events that occurred in Los Angeles on January 17, 1994—the date of a major earthquake affecting the area—were 2-4 times higher than on other days that month.

The cardiovascular phenomenon of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy—frequently referred to as “broken-heart syndrome”—is another example of the sometimes-deadly acute effects of trauma on the heart. When this syndrome occurs, intense emotional stress resulting from a traumatic event such as the loss of a loved one can weaken the heart so severely as to produce an acutely lethal episode of heart failure. For reasons that remain poorly understood, broken-heart syndrome is much more common among women.

The chronic cardiovascular effects of trauma can also be life-threatening. Our fight-or-flight response evolved over millions of years to function as an emergency survival response; it is present in humans and across the animal kingdom with remarkable biological similarity. Modernity, however, has exposed us to a problem our ancestors rarely encountered: chronic stress.

Instead of the historically normal process of HPA axis activation followed by rest and recovery, modern traumas and stressful events frequently result in a fight-or-flight response sustained for months or even years. Considering that our bodies are a type of biological machine, they suffer the same eventual consequences under these circumstances as a car constantly driven at maximum speed. Battered by the unceasing stress response, the heart and cardiovascular system gradually become diseased and dysfunctional, raising the risk of heart attack and stroke.

A Bidirectional Relationship

A final important insight about the trauma-heart relationship is that trauma can be both a cause and a consequence of heart problems. The scientific literature strongly supports a connection between trauma symptoms and acute and chronic cardiovascular risk, but other research convincingly shows that serious cardiovascular events such as heart attacks and stroke frequently cause trauma reactions among survivors. Unfortunately, trauma and other emotional responses are often not assessed in emergency rooms or cardiovascular wards, allowing symptoms to be overlooked or assumed to be transient.

Given this bidirectional and potentially synergistic relationship between trauma and the heart, anyone experiencing acute or chronic traumatic stress should receive education and treatment to reduce their potential cardiovascular risk. And patients being treated for cardiovascular events should be routinely assessed for trauma to identify symptoms that could worsen their prognosis.

Given the consistently high rate of traumatic events in modern society, a failure to appreciate their cardiovascular consequences could have serious public health ramifications. n

Thomas Rutledge, Ph.D., is a professor-in-residence of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and a staff psychologist at the VA San Diego Healthcare System.

The Hidden Shame of Romantic Heartbreak

Breakups invoke painful memories but also unexpected opportunities.

By Mary C. Lamia, Ph.D.

Heartache is a way that we experience the separation of the self from the other. When what feels like the unity of love with a partner is interrupted or ended, we can become acutely aware of our vulnerability. Such a separation is referred to as an “ambiguous loss,” as the person who leaves still exists. Still, we experience grief not only for the individual we loved and (willingly or not) lost but also often for the fantasy of who we thought or hoped they could be.

Heartbreaking Memories

The problem of heartbreak resides within our memories of emotional attachment to the person we lost. Those memories, coupled with the anguish of loss, can keep us in pain. What haunts those who grieve lost love is the ghost of everything good—memories of desire and fulfillment. Distressing, angry, or bittersweet memories may temporarily keep positive memories at bay, but they too represent continued attachment. Negative emotions like anger, disappointment, or disgust do not signal the absence of love; all emotions make us care. To love is to care—to be emotionally invested in another, positively or negatively.

The intensity of romantic heartbreak, research has found, is roughly equivalent between men and women. The post-relationship grief experience involves universal response patterns of physical distress and emotional anguish that may include anger, depression, anxiety, panic, worry, sadness, emotional numbness, nausea, sleep loss, loss of appetite, reduced immune-system function, intrusive thoughts, and decreases in activity in brain regions linked to feeling, motivation, and concentration.

While some people may disavow any fault for the demise of a relationship, others engage in self-blame or continue to seek certainty for the separation decision. Those who have lost love often silently hold onto their grief but they may feel less alone resonating with a song that sublimely expresses the anguish of circumstances in which love is lost or no longer possible.

Shame, and a Path to Recovery

Hidden shame often dominates in the aftermath of romantic loss, accompanied by a powerful longing to restore what has been lost. We generally consider shame to be an emotion of indignity and alienation, felt as inner torment or sickness. However, it also signals the rupture of an interpersonal bond. Imagine you are taking a walk, thinking about a person you recently met for whom you feel an intense attraction. As you round the corner you see that person in the distance, seemingly romantically engaged with someone else. Such moments of shame can leave us feeling defeated, alienated, and lacking in dignity or worth. The experience of inner shame after relationship loss may become so toxic that it is perceived as depression.

We live through others and in them, so when a partner turns away from us we may feel that we’ve become unseen, in a sense that we may believe we cease to be. Some theorists have used the term “ego shock” or “cognitive shock” to refer to a state of psychological paralysis resulting from powerful blows to our self-esteem or pride, in which we are unable to think clearly and we have shame-related thoughts that lead us to imagine the worst and most damaged version of our self.

We have a capacity to recover from the wounds of heartache, but our memory system, which evolved to protect our future choices, may refuse to let us forget. Our brain actively engages with images of a remembered past and may even bring forward earlier unresolved experiences of shame that may have involved another crushing betrayal or recollections of other important personal relationships that had to be surrendered.

Old wounds can leave us with an intolerance of uncertainty that enhances our vulnerability in seeking new love. Nevertheless, if we can recognize shame, and our historical experience of it, we may be able to use moments when we experience a broken bond as unexpected opportunities to look inside, learn, and make ourselves different. n

Mary C. Lamia, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist in Marin County, California.

***********

How an Infant’s Heart Influences Their Mother’s Depression

An infant’s temperament, gauged by studying their heart rate, can have a profound effect on their mother’s postpartum depression, a connection that’s crucial for others to understand.

Although a new birth often brings joy, as many as 1 in 7 new mothers will experience postpartum depression in the year after their baby is born, typically lasting 3 to 6 months, but sometimes leading to chronic or recurring depression.

Babies themselves have distinct temperaments, and some express more negative emotions and have a harder time self-soothing. Babies with less-regulated temperaments can actually change how their mothers feel about themselves as parents, with significant downstream consequences. Recent research explores the underlying physiological basis of this effect.

According to decades of research, patterns of heart rate variability are related to our ability to regulate emotions—that is, a tendency to flexibly adapt to stress and deal with your own feelings is reflected in the patterning of your heartbeats over time. One of the most widely used methods of estimating heart rate variability is to measure respiratory sinus arrythmia (RSA). This measure tries to isolate the activity of the parasympathetic “rest and digest” system as it influences the heart.

Previous research found that infants with lower RSA displayed more negativity and reacted more to new situations, suggesting that RSA might be a basic, physiological indicator of poor infant self-regulation. In a recent study by Jennifer Somers of Arizona State University and colleagues, the researchers followed mothers for 3 years after the birth of their children to gauge how maternal postpartum depression and poor infant self-regulation might combine. They found that if mothers were high in postpartum depression, and their infants naturally had a hard time regulating themselves, there were several negative outcomes, including the mothers feeling less confident in their ability to be good parents and having worse depression symptoms 3 years later.

This study suggests that we can think of the mother and infant as influencing each other. If an infant was “easy,” postpartum depression didn’t matter as much; mothers still felt confident in their ability to parent and didn’t end up with higher later levels of depression. On the other hand, if the infant was more reactive and less able to soothe itself, then postpartum depression did matter. With infants who were naturally more “difficult,” mothers with more symptoms of depression ended up feeling less confident, and their symptoms endured longer than did those of other mothers. Both the mother’s state of mind after birth and the infant’s particular physiology contribute to the way the mother feels throughout the child’s early years.

Many parents worry whether they are doing enough to make sure their children are healthy and happy, but a strong bond is only partially under their control. Children are born with their own personalities and differences in physiology, and this can have a real effect on how the relationship unfolds. Infants who are fussy might present more challenges, leading to very different experiences for mothers. What might be easy or right for one mother won’t work for another, not because of their capacities to parent but because of the needs and demands of their particular babies.

Alexander Danvers, Ph.D., is a social psychologist with an interdisciplinary approach to research.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of this issue.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: bmf-foto de/Shutterstock