Mandela Effect

The Mandela effect refers to the experience of a false memory that is shared by many people.

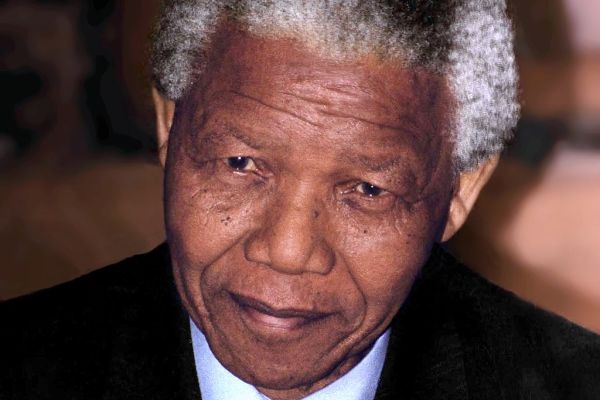

In 2010, researcher Fiona Broome coined the term when she discovered that many people believed, as she did, that anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s. In fact, following his release from prison, Mandela became the president of South Africa and lived until 2013.

The Mandela effect can be found in numerous other examples. In cases of the Mandela effect, people can be surprised, even defiant, that their memory is wrong.

Why would the same specific false memory exist among many people? Researchers cannot fully explain the reason, but several concepts about memory explain parts of the effect.

Memory is malleable, and false memories—memories that seem true and clear in your mind but are somewhat or entirely mistaken—are quite common. Eyewitness testimony, for example, has been unreliable in the courtroom. Memories of the past can be warped by the suggestions of others and incorrectly reconstructed in our minds.

Schema theory may help explain the Mandela effect. According to this theory, our brains encode memories in part through expectations of how things ought to be. We remember the gist of what happened and our minds fill in the details accordingly. Curious George is a monkey and monkeys have tails. Therefore, we remember Curious George with a tail.

Time also plays tricks on memory. Many popular examples of the Mandela effect come from childhood, such as the misperception that there’s a peanut butter brand called Jiffy—it’s Jif—or that the cereal Froot Loops is spelled Fruit Loops.

Research continues about how the brain encodes memories and how they change over time.

A popular example of the Mandela effect is the mistaken recollection of the Monopoly Man character wearing a monocle. In a study by Deepasri Prashad and Wilma Bainbridge, participants were shown several cultural icons with incorrect details, including the monocle and Monopoly Man. While the study participants were able to correctly identify many of the inaccuracies, a large majority recalled the Monopoly Man wearing a monocle.

Yes. It is a well-documented cognitive phenomenon, although researchers are still figuring out why it happens.

Not likely. People have speculated that the Mandela effect is an example of alternate realities getting crossed into parallel universes. The idea for the Mandela effect being a paranormal phenomenon comes in part from the person who coined the term, Fiona Broome, who researched the paranormal. While the precise mechanisms that cause the effect have not been conclusively discovered, there’s a lot about memory and the brain that remains unknown. In contrast, psychologists tend to prefer explanations involving cognitive distortions of memory.

The misinformation effect refers to the creation of false memories as a result of processing new information. In a famous experiment, researcher Elizabeth Loftus demonstrated the misinformation effect by showing study participants a video of a car crash; she noted how recollections of the video differed depending on the phrasing of questions about the crash. In one example, the group of subjects who were asked how fast the cars were going when they “smashed” were more likely to falsely remember broken glass in the video than the subjects who were asked about broken glass after the cars “hit” each other.

There’s no reliable way to know if a memory is accurate, somewhat accurate, or a conflation of several memories and stories you’ve heard throughout life. Many of our memories are at least partially inaccurate.