Anxiety

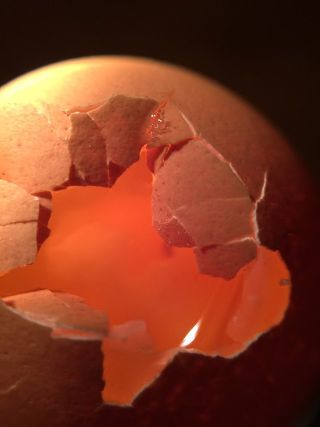

Which Came First, Family Dysfunction or Borderline Behavior?

Family and patient behavior correlate, but which caused which is unclear.

Posted March 29, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- A new study of parents of children with self-injurious behavior indirectly suggests that the parents seem unusually obsessed with their child.

- The authors believe that parents of children with even more severe psychological disorders seem less preoccupied than parents of self-injurers.

- "Blame" is beside the point in looking at dysfunctional family interactions, since everyone in the family is involved.

Parents of people with borderline personality disorder (BPD) who join support groups for themselves like TARA or NEA-BPD strongly believe that any problem behavior they exhibit in relationships with their children is just a reaction to having to deal with children who are somehow not normal. They get angry if they think they are being blamed by the psychiatric profession for their child’s condition.

Chicken vs. Egg

But which came first, the child’s “abnormal” behavior or the parent’s problematic behavior around them? This is a true chicken-and-egg type question. This question is almost impossible to sort out in any empirical study since no one can put a camera on several families, 24 hours a day for long periods of time, to make a determination. Even then it is difficult. For example, a normal but colicky baby may elicit very different responses from a secure parent than from an insecure, ambivalent one, so observers would also have to know quite a bit about what the parents were like before they had a child. There may be a gene-environment interaction.

A new study in a nursing journal, while not directly addressing the question I am raising here, looks at how involvement by the family in the treatment of patients who have BPD might be beneficial. However, some of their descriptions of the relatives they interviewed, and their ideas about them, are highly suggestive of what the answer might be.

Obsession?

The study discusses the experience of Swedish families of people with members who have BPD, and who have access to “brief admission” to the hospital because of recent self-injurious behavior (SIB). In their study, 12 patients, whose age range is not specified, have picked out one of their family-of-origin relatives for the researchers to interview. Those relatives were then interviewed by phone by two of the authors and asked to describe their experiences as the parents of someone with the disorder. The two authors coordinated with each other, and they were basically covering the same types of questions.

Now of course, if a loved one is engaged in SIB, that means that suicide is an issue, even when the SIB had been going on for a long time. Relatives are naturally going to worry more about that person than they might have before the SIB began. However, several points the authors make about their interviewees seem to suggest that the parents were obsessed with the patient to a degree unusual even in that situation. The authors express the opinion that the burden experienced by families of someone diagnosed with BPD involves greater suffering than those with other severe mental disorders.

For example, the authors mention that the interviewers reported that they had to remind the relatives repeatedly not to focus their discussion on the patient, but rather talk about their own experiences. They say the family members’ fears about the children make “it difficult for them to prioritize their own well-being.” The family members have “a hard time allowing themselves to have fun” and were constantly prioritizing their loved ones and ignoring their own well-being. Many of the relatives suffered from their own mental problems and fatigue. They had feelings, not only of helplessness but of anger. "They seemed to have a constant need to monitor their loved ones.”

The study authors do not say if they asked the parents further questions about this level of preoccupation. In particular, they do not report asking whether it may have started even before their child’s SIB began. However, they express the following opinions, which are relevant to my question: “Children can see if someone is unwell and can withdraw and try to make themselves invisible.” “When a parent suffers from mental illness, the children can become carriers of their anxiety.” “Children of parents with mental illness can take a great responsibility for their ill parents.” “The families and their loved ones’ lived experiences are considered to be linked to interactions with each other.”

I agree. These points, along with their observations of the parents, are in accordance with my clinical observations regarding parents of my adult patients with BPD and their parents. It is my view, as elucidated in many of my posts on this blog, that the SIB serves an interpersonal purpose. In many cases, the behavior, in addition to being a reaction to their own distress, is meant to feed into the parent’s preoccupation with the patient.

I believe that the parents’ anxious, angry, and guilty preoccupation comes first, which then leads to their child developing the role of spoiler designed to somewhat control both the guilt and the anger they see destabilizing their parents. The family members then all continue to simultaneously feed into and make worse one another’s problem behavior, especially over the long run. Who is to “blame” is beside the point, because the whole family is reacting to things that have happened to it over several generations. (Blaming anyone is counterproductive because it sidetracks attempts at actually solving these problems).

References

Hultsjo S; Appelfeldt A; Wardig R; Cederqvist J. Don't set us aside! Experiences of families of people with BPD who have access to Brief admission: a phenomenological perspective. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 18(1):2152943, 2023 Dec.