Environment

Tracing the Biophilic Movement to Its 18th-Century Roots

Enthusiasm for nature in our lives is a popular trend with a rich history.

Posted April 16, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- The biophilic movement focuses on our affinity for nature.

- The Romantics of the 18th century opposed the view that nature was objectively removed from humanity.

- Biophilic concerns—reviving an intimate connection to nature and stewarding the environment—trace back to the Romantics and Humboldt’s legacy.

The biophilic movement is gaining momentum. For example, the upcoming Biophilic Leadership Summit offers a “multi-day conference entirely focused on biophilic projects, research & principles, bringing together top industry thought-leaders in an intimate natural setting to network, build partnerships and learn from each other.”

The term biophilia is attributed to the psychoanalyst Eric Fromm (1976) and was popularized by the biologist E. O. Wilson (1986). As commonly understood, the term refers to humans' innate affinity for nature as a psychological orientation (Fromm) and as an evolutionary adaptation (Wilson). In the context of architecture and design, the questions raised are how to best bring nature and patterns from nature into the built environment to enhance our well-being.

Biophilic ideas emerge at the junction of people’s relationship to nature, art, and science. The conceptual currents that carried us to this moment can be traced back to 18th and early 19th century Europe, a time when the Enlightenment blossomed and its Romantic critics struggled with tensions between a world that could be quantified and controlled and a world that was experienced through emotions and imagination.

The Enlightenment and its critics

The Enlightenment brought rationality to the fore and cast people into a specific relation to the natural world. Nature could be observed carefully; animals, plants, and matter could be classified; their properties could be quantified; the world could be understood. Experiments, by manipulating variables in a controlled manner, exposed causal relations. The same experiments could be run by anyone, presenting an objectivity not vulnerable to the vagaries of any one person. Hidden forces like atmospheric pressure, gravity, and electricity could be revealed and harnessed. From these insights, the Industrial Age belched out innovations like steam engines, textile mills, and the telegraph. Nature was tamed, resources extracted, and our lives improved. Or so the story went.

Enter the Romantics. In her book, Magnificent Rebels, historian Andrea Wulf (2022) recounts the remarkable gathering of minds in Jena, Germany, at the end of the 18th century, who opposed a view of progress constructed on a desiccated view of nature in which quantity replaced quality and reason trumped emotion. Led by Goethe, the group included intellectuals and poets like Schiller, the Schlegel brothers, Fichte, Schelling, and Noval. For example, Schelling (1799) in Naturephilosophie elevated the role of the self as a dynamic and integral part of nature. Nature permeated the self at levels below consciousness, but could be accessed through art. While these seminal thinkers differed in their view of science, they sought to dissolve the separation between mind and world, underscored the importance of emotions in our relationship to nature, and promoted the role of art in understanding this relationship.

Alexander von Humboldt

Although not a household name in the U.S. today, Alexander von Humboldt was the world’s most famous scientist in the first half of the 19th Century (Wulf, 2015). As a young man, he was influenced by the group in Jena. In the 1790s he conducted anatomic dissections and “galvanic” experiments with Goethe who, better known as a poet and dramatist, was also a scientist (e.g., he wrote about color theory and optics). A polymath, Humboldt immersed himself in nature. From 1799 to 1804 he traveled through South America, paddling through rivers in the rainforest, traversing vast plains, climbing the Andes, and examining volcanoes. The entire time, he collected specimens, made detailed measurements, and copiously charted his findings.

A consummate scientist, Humboldt was driven by a wonder of nature. He viewed emotions and memory as essential to understanding the world. His narrative writings infused meticulous observations with subjective impressions and imagination. He became a model of nature writing, making science accessible and popular. He identified isotherms—climactic bands across the world in which similar foliage grow, having adapted to similar environmental conditions. At Lake Valencia in Venezuela, he observed how deforestation and irrigation destabilized an ecology. He highlighted the importance of biodiversity and opposed the monoculture of cash crops like indigo, sugar, and cotton, which replaced nourishing mixtures of fruit and vegetable growth. He saw that cash crops propelled colonialism and devastated the environment in its wake.

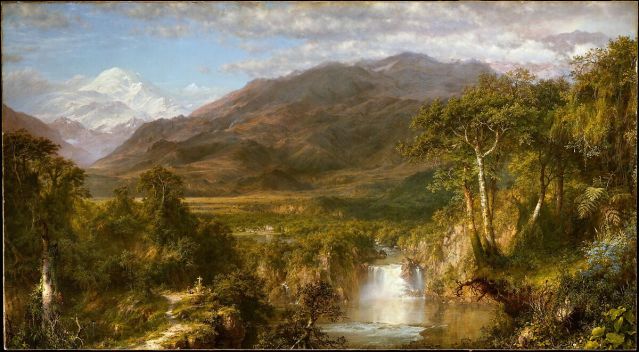

Half a century later, a young American painter, Fredrick Edwin Church, followed in Humboldt’s footsteps in South America and painted The Heart of the Andes. The large painting combined beauty and careful scientific detail and was a sensation when shown in New York a few days after Humboldt died. It depicts the landscape through which Humboldt traveled to climb higher than 19,000 feet, close to the peak of the volcano Chimborazo. This altitude was the highest any European had set foot at the time. Later, he talked about appreciating nature from a high vantage. On the heights of Chimborazo, as he absorbed the vista before him, Humboldt had his critical insight that nature was an enormous interconnected web.

Humboldt’s legacy

Humboldt’s influence spanned the world. In the United States, he engaged with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Madison later expressed concern for deforestation and the effects of large-scale Virginian tobacco farming on the environment. Henry David Thoreau immersed himself in Humboldt’s popular writings and similarly came to believe that nature needed to be understood as an interconnected web. George Perkins Marsh, who helped establish the Smithsonian Institution, was a Humboldt acolyte. Marsh traveled in the Middle East in the mid-19th century and with a Humboldtian eye saw how humanity could devastate a landscape. On his return, he was concerned about how American industry was wreaking havoc on the American environment. His book Man and Nature, published in 1864, had a huge impact on the American conservation movement. John Muir, inspired by Humboldt, dreamed of traveling to far-off lands in the South. His plans were interrupted, and he ended up spending much of his life in the Sierras. He also believed that nature needed to be understood through our emotions as much as through science. His popular writings brought the beauty of nature before the general public and he founded the Sierra Club dedicated to preservation.

The biophilic movement is preoccupied with an appreciation for life and our intimate relationship with nature. Biophilia prioritizes our well-being and the well-being of the environment. It is concerned with beauty and our emotional response to nature and with environmental stewardship: biodiversity, sustainability, conservation, preservation, and climate change. It pushes against a view of progress in which natural resources are simply commodities to be exploited. These rich ideas that animate contemporary biophilic thinking are rooted in the passions of the romantics and the global vision of Alexander von Humboldt in which people, science, nature, and art are inextricably bound.

References

Fromm, E. (1974/1992). The anatomy of human destructiveness. Macmillan.

Marsh, G. P. (1864/2003). Man and nature. University of Washington Press.

von Schelling, F. W. J. (1799). Einleitung zu seinem entwurf eines systems der naturphilosophie. Oder: ueber den begriff der speculativen physik und die innere organisation eines systems dieser wissenschaft. Von FWJ Schelling. Bey Christian Ernst Gabler.

Wilson, E. O. (1986). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

Wulf, A. (2022). Magnificent rebels: The first Romantics and the invention of the self. Knopf.

Wulf, A. (2015). The invention of nature: Alexander von Humboldt's new world. Knopf.