Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Can Art Be Data?

The case of art therapy for veterans with posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Posted May 30, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- For art to serve as data, it needs to be quantifiable and subject to empirical or experimental examination.

- By assessing the impact of art produced by people with PTSS during art therapy, we tested the therapy's value.

- Changes in the art made before and after therapy demonstrated the salutary effect of art therapy.

At an interdisciplinary conference, I heard a scholar from the humanities refer to art as data. What could that casual reference actually mean? Art serves many purposes. It can facilitate communication. It can promote social cohesion. It can express emotions. But how do any of these functions of art provide information that a scientist would consider data? Can art take quantitative form that could be used to make empirical comparisons and even to drive experiments that test hypotheses?

Testing a hypothesis

We recently published a paper (Estrada Gonzalez et al., 2024) in which we show how art can in fact become data in a way that most scientists would accept. We tested our hypothesis using participants who were blinded to the relevant conditions and measured an important aspect of art that was subject to statistical analyses.

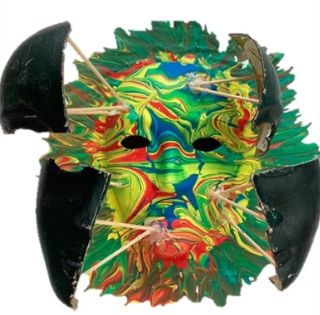

What was the problem and the hypothesis under consideration? Military personnel frequently experience distressing symptoms following psychological trauma. Posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) are not treated easily, and conventional medical interventions have limited success. We are collaborating with the National Intrepid Center of Excellence at Walter Reed Military Medical Center in which an art therapy program is offered to military personnel to alleviate PTSS. In this program, veterans paint a self-portrait on a blank paper mâché mask at the beginning of their sessions and then again after they have completed the program. Because veterans with PTSS often have trouble expressing their emotional state in words, their paintings provide an alternate way to express their affective state. Once these emotions are externalized in the masks, the artworks can be used further as a vehicle for talk therapy. Using their art, we wished to formally test the hypothesis that art therapy has a salutary effect on people with PTSS. To do so, we needed to quantitatively measure what emotions are expressed in these masks and if that expression changes with therapy.

The impact of art

In a different line of research, we identified cognitive and emotional impacts that art can have on a viewer (Christensen et al., 2023). Using expert input and then crowdsourcing semantic associations, we identified a taxonomy that characterizes aesthetic experiences. Analogous to the way a sommelier might offer a vocabulary with which one can appreciate a complex sensory experience like wine tasting, we propose that a vocabulary that identifies different flavors of an aesthetic experience can help characterize and enrich that experience. We identified 69 potential cognitive and emotional impacts of art. We organized this semantic network into 11 dimensions of aesthetic experience, which could be further reduced at a coarse level into four categories of experience: engagements characterized by (1) positive affect, (2) negative affect, (3) an attentive/immersive state, and/or (4) new understanding (epistemic transformation).

Our taxonomy gives us a measure with which to quantify an important aspect of any art—its expressive qualities and potential impact on viewers. With this measurement tool in hand, we turned to the masks made by veterans before and after their therapy. Using 10 masks, five made before therapy and five after, we crowd-sourced them to assess the impacts that could be appreciated in these images. The participants in this study were blinded to which masks were made before and which masks were made after treatment. The 11 dimensions of the taxonomy were used to assess the viewers’ emotional read of the masks and to test for any differences between the masks made before or after therapy.

The art in art therapy

We found that viewers experienced the initial masks to be more angry, upset, and challenging than the later masks. While people with PTSS often describe themselves as feeling numb, they could express negative emotions in their masks. Similarly, viewers found the masks made at the final stage of therapy expressed more calm and pleasure than the masks made at the initial stage. These observations are consistent with the idea that the therapeutic intervention helped veterans to balance their emotions. Finally, participants exhibited a clear preference for the masks created during the later stages of therapy, rating them as more beautiful and expressing a greater liking for them compared to those from the initial stages. This preference appears to be linked to depth of engagement, as participants reported feeling more immersed in the viewing experience of the final-stage masks. These observations suggest that as therapy progressed, the masks not only served as a medium for emotional expression but also reflected the transformative power of art therapy and gained artistic value.

Using a novel measurement tool, our art impact taxonomy, we presented evidence supporting the hypothesis that art therapy has a salutary effect on the emotional state of people suffering from PTSS (Estrada Gonzalez et al., 2024). The emotional dimensions of self-portrait masks made before and after art therapy demonstrated that blinded participants were sensitive to the intervention’s impact. In this case, art was data—data that demonstrated the efficacy of art therapy.

Acknowledgment: The research cited was supported by the Henry Jackson Foundation, The National Endowment for the Arts, and the Templeton Religion Trust.

References

Christensen, A. P., Cardillo, E. R., & Chatterjee, A. (2023). What kind of impacts can artwork have on viewers? Establishing a taxonomy for aesthetic impacts. British Journal of Psychology, 114(2), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12623

Estrada Gonzalez, V., Meletaki, V., Walker, M., Payano Sosa, J., Stamper, A., Srikanchana, R., King, J. L., Scott, K., Cardillo, E. R., Rhodes, C. S., Christensen, A. P., Darda, K. M., Workman, C. I., & Chatterjee, A. (2024, 2024/03/26). Art therapy masks reflect emotional changes in military personnel with PTSS. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 7192. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57128-5