Attachment

Understanding Love and Hate After Cheating

A romantic partner who cheats disrupts our response to seek safety from them.

Posted March 15, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Betrayal puts our attachment system and threat response systems in conflict.

- Each system tells us to do something different to stay safe.

- Our attachment system says to reach for a connection, the threat response system: distance for protection.

- This internal conflict creates confusion and chaos in the behaviors and emotions of betrayed partners.

What happens when our romantic partner, the person we trust to have our back, is the one we turn to for support and comfort in the middle of stress and challenges? What happens when that person becomes the source of our pain and distress through the betrayal of infidelity?

Betrayal at the hands of our most significant other plunges us into an acute relational dilemma that I have named attachment ambivalence. Understanding attachment ambivalence—what it is, why it happens, and its reactions—is vital to addressing and overcoming betrayal trauma.

John Bowlby, the father of attachment theory, identified human attachment as a motivational system. This means we are wired for bonding. Not only that, but our attachment system is also our best regulatory tool. When we experience stress, our attachment system fires, prompting us to reach out to connect with others. Connection soothes our nervous system and helps us come back into balance.

Most of the time, our attachment systems and threat response systems sync up and work well together[i]. When we have a stressful moment at work, we text our partner. When we fight with our sister, we talk it through with our significant other. We experience stress, and we reach for connection.

Betrayal disrupts these systems and puts them at odds with one another. Our romantic partner is our adult attachment figure[ii]. Because they cheated and introduced fear, pain, and panic into the relationship, they no longer feel like a haven we can turn to.

Betrayal causes our threat response system to fire hard and fast. We do not have a rational, reasoned, gracefully equipped response. We have a screaming caveperson reaction. We lose our minds. Completely and totally. We are under threat, and we might not survive.

Betrayal creates the primal panic of disconnection by turning our partner into a source of danger. Our safe base has just tried to kill us. That is how it feels to the body, and our body reacts from a self-preserving instinct that says, “Restore safety now, by any means and at any cost.”

This is where ambivalence—the state of feeling two contradictory emotions at the same time—enters the picture. Our threat response and attachment systems are now at war.

On the one hand, connection with our partner is our best route to soothing our distress. When we are connected, we feel calm, grounded, relaxed, able, and supported. Our attachment system prompts us to reach for a connection to restore safety.

However, now our partner is also our greatest danger. Instead of protecting us from the tiger as they promised, they became the tiger and mauled us. Instead of having our back, they turned and twisted the knife to the hilt. What if they hurt us again? Our threat response system demands we distance ourselves or fight off the danger our partner now represents.

Our instinctual drive for safety is pulling us in two opposite directions: We seek the relief that connection can provide while simultaneously distancing ourselves from danger. The instinct to connect and the instinct to disconnect, both primal safety-seeking imperatives, are now in conflict within us.

This is the relational dilemma created by betrayal. The ambivalence we feel about our significant other can make our feelings and behavior unpredictable, chaotic, and confusing, even to ourselves[iii].

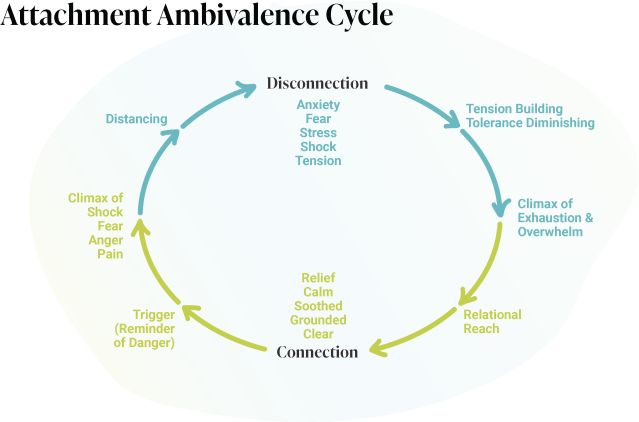

Attachment ambivalence is often experienced as a cycle.

To help us understand how this cycle plays out, imagine this scenario.

You wake up lying next to your partner. For a few moments, you enjoy the warmth and safety of this position.

Suddenly, though, you feel a lurking dread. Something is terribly wrong if only you could remember what. Seconds later, memory slams into you: your spouse cheated. You don’t know all the details yet, but what you do know has torn your world apart.

You roll away, your body rigid with fear and anger. You ask yourself, how could they? And how can I survive?

As your partner gets up and ready for work, you don’t speak—your energy accuses them at every turn. When they tell you for the umpteenth time how sorry they are, you say nothing, just waiting for them to leave. You spend the rest of the day fuming with anger and plummeting with grief. Your only relief comes through a short nap between projects.

That night, when your kids return from school, you go on autopilot. Later, when your partner walks in the door, exhausted and unsure of the welcome they’ll receive, you sit down for dinner. The familiarity of a hundred meals together begins to thaw the air.

You’ve spent enormous energy protecting yourself all day, but by bedtime, you’re exhausted. You’re sad, lonely, and sorely in need of comfort. You curl up against your partner and close your eyes while tears of relief and sadness roll down your cheeks. You’re both careful not to say or do anything to ruin the moment. Maybe you even make love in a spell of intense connection. Then you sleep in deep relief.

You still don’t feel like yourself the next morning, but you are better than yesterday. At lunchtime, you break from work to watch your favorite TV show. But in this episode, your favorite character gets cheated on. Suddenly, you’re back in the vortex. The agony of betrayal steals your breath. You text your partner a flurry of accusations and expletives as your need for protection rushes back.

If this scenario sounds familiar, you’re not alone. The simultaneous need for distance and connection creates a push-pull dynamic. While you’re spitting mad and crying your eyes out, you also want your partner to soothe your pain. While you want them to move out, you also want them to hold you while you wail at the top of your lungs. While you know they’re lying, you also desperately hope they’re telling the truth. While you never want them to touch you again, you crave the comfort of making love.

So, how do you reconcile this?

First, permit yourself to experience both needs—the need for distance and closeness—even though they feel contradictory. When you’re angry, hurt, and afraid, it’s OK to say to your cheating partner, “I’ve been really angry with you all day today. I need space, so please give me room tonight.”

When you need to feel closer—talking, being held, or hearing about your partner’s healing process—ask for that as well. You may say, “I need a connection right now. Can we take a walk and talk?”

It’s normal to desire both connection and distance after betrayal, so allow yourself to feel both—without judgment or a forced move in either direction. As you permit these feelings, you’ll be better able to process, make decisions, and heal.

It’s also vital for therapists to understand attachment ambivalence and its dynamics. Betrayed partners are often confused by their contradictory thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Normalizing their experience and helping them start to identify and articulate what they need at different points in the cycle is vital.

The cheating partner can also be flummoxed by the push-pull in the relationship and have no idea how to be supportive. A skilled therapist can guide both individuals in navigating this normal response to betrayal while respecting each person’s experience.

To find a therapist, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

[i] Bowlby, John. Attachment and Loss: Volume 1: Attachment (New York: Basic Book, 1969).

[ii] Mario Mikulincer and Phillip R. Shaver, Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change (New Yor: Guilford Press, 2007) 16.

[iii] Robbie Duchinsky, “The Emergence of the Disorganized/Disoriented (D) Attachment Classification,” History of Psychology 18, no 1 (2015): 32.

Adapted from The Betrayal Bind: How to Heal When the Person You Love the Most Hurts You the Worst, by Michelle Mays LPC, CSAT-S, Central Recovery Press, 2023.