Bias

Dogs Are Not Actually Fully Colorblind

Dogs do have color vision but it differs from the color vision of humans.

Posted May 25, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Many people believe that dogs are colorblind, however data shows that they are able to see a range of colors.

- Research has shown that the visual receptors that respond to seeing the color red are absent in dogs.

- The particular form of color blindness which dogs have does make it difficult for canines to perform certain tasks.

If you ask the average person whether or not a dog sees colors they are apt to give you the stock answer that dogs are colorblind. That is true; however, people misinterpret that particular fact as meaning that dogs see no colors and that for canines the world appears to be much like a black-and-white photograph. Actually, dogs do see colors, but the colors that they see are neither as vivid nor as varied as those seen by humans. It may be interesting to give you a peek as to what the world looks like through a canine eye.

What Is Meant by Colorblindness?

If we look into the eyes of people and dogs we would find that both contain special light-catching cells called cones which are tuned to respond to color. We have a lot of cones in our eyes and dogs have fewer, suggesting that their color vision won't be as rich or intense as ours. Much more important, however, is the fact that humans have three different kinds of cones, each tuned to a specific wavelength and it is that which allows us to have a full range of color vision. The situation is different in dogs.

The most common types of human colorblindness come about because a person is missing one of the three kinds of cones. Such individuals can still see color, but a much more limited range than normal people.

What Kind of Color Vision Do Dogs Have?

Jay Neitz at the University of California in Santa Barbara proved that dogs do have some color vision. It was painstaking work, involving many test trials extending over months. During testing, dogs were shown a computer-controlled display of three light panels in a row. For every trial, two of the panels were the same color, while the third was different. The dog's task was to find the one that was different and to press that panel. If it was correct, the dog was rewarded with a treat that the computer dispensed to a cup below the panel.

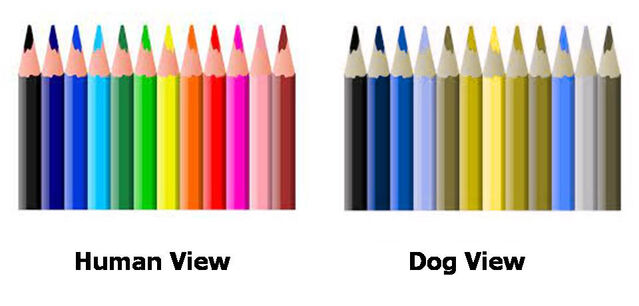

After analyzing canine responses to thousands of color presentations, Neitz was able to conclusively show that dogs do see colors, but many fewer than normal human beings. The dogs act as if they are missing the cone which normally responds to longer wavelengths of light which we see as red. This means that dogs see the colors of the world as basically yellow blue and gray. They see the colors green, yellow, and orange as yellowish, and violet and blue as blue, while blue-green is seen as gray. The red-colored objects basically lose their hue and become quite dark since the dog's eye is lacking the receptor to respond to red. To give you an idea of what that looks like, here is viewed a set of colored pencils with a normal human eye and as if viewed by a dog.

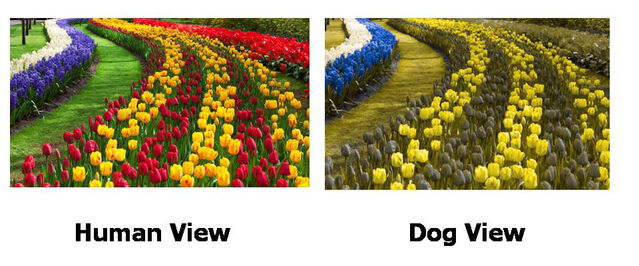

Perhaps the situation will be clearer if we look at this garden, in which tulips are arranged in rows by color. Notice that in the dog's-eye view the red color is lost and its hue is not distinguishable from the green of the grass except that it is darker.

In a more complicated scene, the absence of red-responding receptors can make a colorful scene (to the human eye) appear to be quite drab, as in this view of a canal from the Island of Burano in Italy.

What Are the Implications of Red-Blindness in Dogs?

The lack of a full range of color discrimination on the part of dogs will make certain tasks more difficult. For example, in humans, the task of picking cherries from a tree is an easy one because the red of the cherries is clearly discriminated from the green of the leaves. For dogs, such a task would not be easy. The only way dogs could do this would have to be based on finding round objects among the leaves because they get no help from color differences.

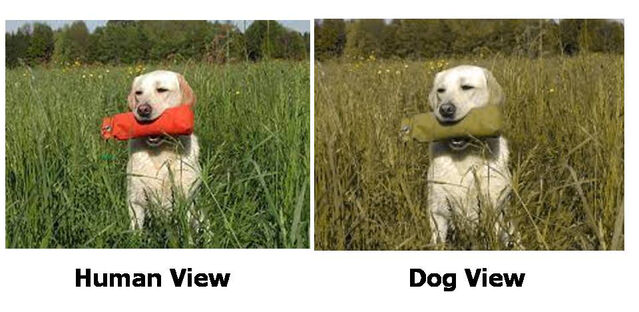

The fact that dogs are red-blind is not well understood by most people, which has led to an interesting conundrum (for dogs at least). Right now, the most popular colors for dog toys and retrieving objects are red or safety orange (the bright orange-red color you see on safety vests or traffic cones). Since many dog toys were designed to be tossed out onto green grass for the dog to chase and bring back it would make sense for the toy to be easily seen against the green of a lawn or field. Unfortunately, because of the nature of the dog's visual system, a red toy on a green background is virtually invisible.

So why are dog toys in these colors so popular? It should be obvious that this is because the toys are not being bought by dogs, but rather by humans—specifically humans who are highly responsive to the color red and they simply make the presumption that their dogs see colors the same way that they do.

Copyright SC Psychological Enterprises Ltd. May not be reprinted, reposted without permission

References

Neitz J, Geist, T Jacobs GS (1989), Color vision in the dog, Visual Neuroscience, 3, 119-125.

Coren, S. (2004). How dogs think: Understanding the canine mind. New York: Free Press.

Pongrácz, P., Ujvári, V., Faragó, T., Miklósi, Á., and Péter, A. (2017). Do you see what I see? The difference between dog and human visual perception may affect the outcome of experiments.Behavioural Processes, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2017.04.002