Freudian Psychology

The Unknown vs. the Mysterious

One must distinguish the mysteries of Freud and Jung from those of neuroscience.

Updated January 18, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Freud and Jung were trying to crack the mystery of the mind.

- Their mystery was actually restricted to semantic processing.

- Semantic processing is not considered a mysterious "anomaly" of the scientific approach.

- Consciousness, which was not their focus, remains a true mystery.

.jpg?itok=83n6OtmG)

Freud was interested in what a particular dream, slip of the tongue, or object meant to an individual. For example, a young man once told Freud about a recurring dream, one involving a river and certain strange events. Freud reasoned that the symbols in the dream reflected that the young man was anxious of a particular possibility—becoming an unexpectant father. The young man did not see this link between the symbols in the dream and his own fears. Jung was interested in what symbols mean, not just to the individual, but to all humanity. According to Jung, these meanings could be inborn and stored in what he called “the collective unconscious.”

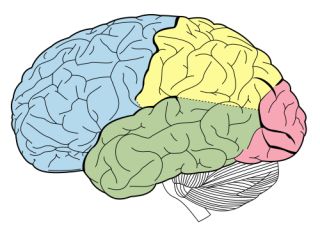

Thus, Freud and Jung attempted to illuminate what symbols mean to an individual (because of his or her life history) or to everyone (because of inborn knowledge or shared experiences). To them, the mysteries of the mind concerned the deep, true meaning of mental events. Thinking of water actually means X, which is really not about water, and dreaming of falling really means Y, which is not really about falling. To them, one does X (e.g., a slip of the tongue) because of Y, which is not obviously related to the malapropism. One dreams of falling, because one is worried that one’s soccer team will be dropped to second division, for example. Regarding the brain, Freud and Jung were interested primarily in “semantic” (meaning) processes, which are largely carried out by the medial temporal lobes. It is important to circumscribe the kinds of processes in which they were interested. As in the anecdote above, semantics are often associated with one’s desires and motivations.

Of course, the popular press became interested in these insights, and of course, people at cocktail parties wanted to discuss the deep meaning of their own dreams and random thoughts. All symbols and thoughts held by one now became much more special. Regardless of the validity of the conclusions by Freud and Jung (many of which were controversial), it is important to note that these mysteries concern semantics—that is, the meaning of things. And the meaning of things naturally varies to some extent across individuals. The sight of a piano means one thing to a frustrated musician; it means something else to a young child; and it means yet a different thing to a piano tuner. And the sight of certain colors might sadden someone who is a fan of a soccer team that wears those colors and that just lost a very close match.

Freud, through various kinds of analyses, was trying to ascertain the deep meaning of dream images, actions, and out-of-the-blue thoughts for an individual. To find out the true meaning, one must know much about the individual, about his or her history. The conclusions about the meaning of a symbol might be correct or wrong, but in either case, the question was about the true, deep meaning of the symbol (e.g., the meaning of “the sun”).

When an undergraduate student participates in one of my experiments, I do not know all the associations that he or she has toward, say, the image of a sun or a dog. For the latter, the image could be a generic line drawing of the dog. This would be the stimulus, and the activations in the temporal lobes in response to the stimulus would be the “semantic activation.” The participant might be a dog lover or could be a dog trainer or could be fearful of dogs, because of some past event that may or not be remembered (e.g., a dog barked at the participant when he or she was very little). Thus, to me, the experimenter, the meaning of “dog” to a particular participant is an unknown, at least to a consequential extent. To me, this is an unknown. However, that a stimulus will activate mental associations and meanings is, at least conceptually, not a real mystery today in cognitive science.

It is true that much is unknown about the semantic process, certainly, but it is not a mystery in the sense that it is what the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn would call an “anomaly” in the current scientific approach. There are plenty of neural network models, and other kinds of models, that explain how neurons in the temporal lobe reflecting “semantic representations”—the meaning of objects or words—can be activated by external stimuli and possess meanings that are peculiar to an individual. Freud and Jung were trying to crack the ‘mystery’ of what a particular thing meant to an individual (or humanity, in the case of Jung). This was their mystery about the mind. But this is not a deep mystery regarding how the mind works. What is a deep mystery, and continues to be an “anomaly” in the current approach of the cognitive sciences is how neurons are capable of generating conscious states, the subjective experiences that you and I have every day, every waking moment—and in dreams. The neurons, each of which is unconscious, form networks that, somehow, create conscious experiences, be they of after-images, the smell of coffee, or ringing in the ears. The cardinal mystery regarding how the mind works is consciousness. It is important to note that Freud and Jung were trying to crack a different kind of “deep” puzzle.

References

Morsella, E., Godwin, C. A., Jantz, T. K., Krieger, S. C., & Gazzaley, A. (2016). Homing in on consciousness in the nervous system: An action-based synthesis. Behavioral and Brain Sciences [Target Article], 39, 1-17. I