Confidence

The Benefit of the Doubt: Do Experts Know Their Unknowns?

Research shows a new perspective on the confidence of experts versus laypeople.

Updated May 8, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- A new study explores the differences in confidence judgments between experts and nonexperts in various fields.

- Experts are generally less overconfident than nonexperts and aligned with their own knowledge.

- However, while experts are good at recognizing their correctness, they are less aware of their errors.

Most of us would probably agree with this quote attributed to the Chinese philosopher Confucius: “To say you know when you know, and to say you do not when you do not. That is knowledge.” However, do we live up to this ideal, especially the part about admitting ignorance? And how do experts differ from nonexperts in this regard? That’s a question investigated by Yuyan Han and David Dunning in a new article published in the Journal of Behavioral Decision Making.

Experts tend to have greater knowledge in the fields in which they work. In most cases, this means they are better at making decisions or predictions in those areas. Meteorologists have been mentioned as a perfect example of a profession that fosters good metaknowledge—what people know about their own knowledge. Not only is their work fairly routine with frequent repetitions (e.g. daily forecasts), but they also work with probabilities and get consistent feedback about their predictions in the form of the actual weather that follows (e.g. a day later). This provides meteorologists with the perfect conditions to have good metaknowledge and avoid overconfidence (thinking they know more than they actually do).

Other experts have to deal with outcomes that are much more difficult to predict. Take the expertise of finance professionals, for example. Movements of financial markets are notoriously uncertain and stock prices are extremely difficult to forecast. One study found that experts were unable to predict stock prices better than chance. A frequently used metaphor refers to monkeys throwing darts at a board being just as good at predicting those kinds of outcomes! Despite all this, finance professionals are not immune from overconfidence.

In their research, Han and Dunning investigated confidence judgments in three fields of expertise: climate science, psychological statistics, and investment. They asked both experts and nonexperts a series of true-or-false questions. For each question, individuals had to rate their confidence in the answer they had given. The lowest possible confidence rating was 50%, reflecting the probability of being right in a true-false guess. The highest possible rating was 100%.

This allowed the researchers to calculate scores for individuals’ actual performance (percent correct), average confidence ratings, and overconfidence (confidence versus actual performance). They found experts to be generally less overconfident than nonexperts. The quality of individuals’ metaknowledge could be seen in calibration—how well performance at a given confidence level matches that confidence. Compared to nonexperts, they found that experts had better calibration.

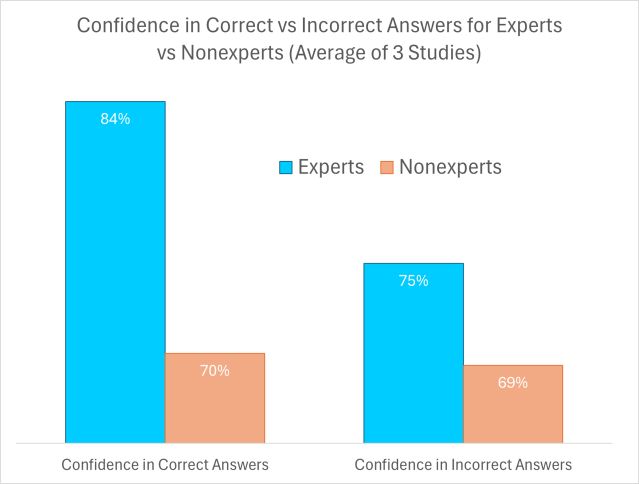

A different pattern emerged when the researchers analyzed how much experts' confidence aligned with what they knew and what they did not know. Perfect confidence alignment would be a 100% confidence rating for correct answers and 50% rating for incorrect answers, leaving a large separation between the two types of ratings. As expected by the researchers, the data from their three studies combined shows that this separation is larger on average for experts (84% vs 75%) than nonexperts (70% vs 69%).

However, the difference between experts and nonexperts is much more pronounced for correct answers (84% vs 70%) than incorrect ones (75% vs 69%). In other words, the separation between the two groups is mainly due to experts being more aligned with what they know rather than what they do not. Experts may have better metaknowledge overall, but they aren’t as good at knowing when they don’t know. Compared to nonexperts, experts express more confidence when they are right, but not more doubt when they are wrong.

Han and Dunning reflect on what these results suggest with respect to the concepts of knowledge and expertise. Experts don’t appear to live up to the philosophical ideals of thinkers like Confucius, as they are more likely to recognize what they know than what they don’t know. They speculate that one possible explanation could be found in our reward system, which has a positive bias towards “assertive knowledge”. For example, the publication bias in scientific literature demonstrates that people are more interested in reading about research that supports a hypothesis than one that does not.

On an individual level, encouraging people to learn from mistakes can help reduce overconfidence among both experts and nonexperts. In their final remarks, the authors acknowledge that a lack of knowledge is not a problem in itself. It becomes a problem if there is also a lack of awareness of one’s lack of knowledge, because it can stand in the way of gaining knowledge, listening to others’ advice, and making good decisions.