Gender

Too Close, Too Far Away, or Just Right?

Researchers have measured preferred interpersonal distances in 42 nations.

Posted May 13, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

In 1966, anthropologist Edward T. Hall presented his classic analysis of human spatial behavior in a slim volume titled The Hidden Dimension. Hall posited that cultural norms are the most important factor in determining preferred social distances between people. Gender and social settings are also important, wrote Hall, but cultural practices are most important.

Hall grouped societies into two categories—contact cultures (Latin Americans and Arabs, for example) and non-contact cultures (Northern Europeans and Japanese, for example). According to Hall, contact cultures prefer closer interpersonal distances and engage in more touching.

Anecdotal evidence in support of Hall's theory has always been plentiful, but systematic observations across cultural groups were surprisingly sparse until an international team of researchers led by Agnieszka Sorokowska and Piotr Sorokowski (at the University of Wroclaw in Poland) reported the results of a 42-nation study.

The researchers recruited 8,943 participants from 42 countries. Their ages ranged from 17 to 88, with most participants over the age of 30. About 55 percent of the participants were women.

The study participants completed three versions of a simple task. They looked at a sheet of paper that showed two human-like figures standing apart and facing each other. The two figures were separated by a distance scale that represented 220 centimeters (86.6 inches or 7.2 feet).

In the first version of the task, a participant was told that he or she is Person A, and Person B is a stranger. At what distance would you feel comfortable talking with Person B? Mark that distance on the scale.

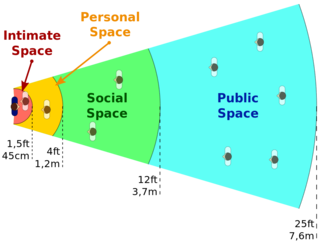

In the second version, Person B was said to be an acquaintance. In the third version, Person B was a close friend. (The three versions are said to measure social distance, personal distance, and intimate distance, respectively.)

As expected, preferred social distances (135 cm or 4.4 feet, on average) were larger than preferred personal distances (92 cm or 3 feet, on average). Likewise, preferred personal distances were larger than preferred intimate distances (32 cm or 1 foot, on average).

The pattern (social > personal > intimate) was observed in every country, but cross-cultural differences in the distances themselves were large. In terms of personal distance, for example, Argentina and Peru were at the "closest" end of the scale (about 62 cm), while Hungary and Saudi Arabia were at the "farthest away" end of the scale (about 105 cm).

Across countries, the correlation between preferred personal distance and preferred social distance was strong (r = .69), as was the correlation between preferred personal distance and preferred intimate distance (r = .70). In other words, if we know the preferred personal distance in a country or cultural group, we can predict fairly accurately the preferred social and intimate distances in that same country or cultural group.

The researchers also observed that older people and women typically preferred more distance when talking with an acquaintance. The differences were not large, usually no more than a centimeter or two, but they were reliable (that is, trustworthy).

Sorokowska, Sorokowski, and their colleagues acknowledged three limitations to their study. First, the sex of Person B (the approaching person) was not specified. The absence of this critical information may have muddled the choices made by participants.

Second, the samples in the various countries were relatively small, usually no larger than 200 persons. As a result, study participants may not have adequately represented the larger populations of their respective countries.

Finally, the study participants indicated their preferences in three hypothetical scenarios but did not actually engage anyone in conversation. Our predictions of what we want and how we will behave don't always match up with what we actually do.

References

Hall, E. T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Sorokowska, A., Sorokowski, P., Hilpert, P., Cantarero, K., Frackowiak, T., Ahmadi, K., ... & Blumen, S. (2017). Preferred interpersonal distances: A global comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(4), 577-592.