Emotional Intelligence

Why Mansplaining Might Not Be What You Think It Is

An often impulsive mislabelling of poor cross-sex mindreading.

Updated July 19, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- "Mansplaining" accusations risk hindering opposite-sex friendships and relationships.

- Men often build same-sex relationships through knowledge-driven conversations lacking emotional elements.

- Applying this method to women can be seen as condescending, rather than an attempt to foster a relationship.

- Understanding sex differences in communication can help cross-sex relations, avoiding misinterpretations.

“Mansplaining” is an accusation thrown around often and risks getting in the way of forming opposite-sex friendships and relationships. Typically, when someone says they’ve been a “victim of mansplaining,” it’s in the context of a man talking to a woman about a topic she already knows about. She perceives his sharing as a condescending or patronising lecture, given intentionally, perhaps in an attempt to put her down.

There are some men who do this. It’s not nice and I don’t condone it. However, I think more commonly it’s an accusation rashly levied at men by those disregarding something fundamental about male communication.

How men build relationships

When building same-sex relationships, men often go about this in a different way from women. Male-to-male conversations can be dominated by the exchange of knowledge and recommendations about things: Statistics about sports stars, potential fixes for botched DIY jobs, and motorway routes for long trips. The list goes on.

Such exchanges don’t necessarily impart accurate information. Men, being human, can waste several hours sharing “facts” which sometimes have no grounding in reality whatsoever. The point is that their chosen topics of conversation are more systemising in nature, often lacking an emotional, empathising component.

Now, to be clear, this isn’t saying that men never share their feelings or that women never talk about practical problem-solving. But it’s showing that there’s an imbalance and that the type of conversation that men use to build and cultivate same-sex friendships can be different from that of women.

An illustration of sex differences

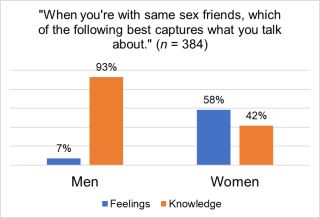

To illustrate, I recently ran a Twitter poll asking almost 400 people: “When you’re with same-sex friends, which of the following best captures what you talk about?” People could choose either “Knowledge” or “Feelings.” This forced-choice question made people consider what dominates their conversations the most.

The results were quite surprising. Women were fairly balanced, with 58 percent of the respondents saying that feelings better reflected the focus of their conversations. Among men, it was the opposite, with 93 percent responding that knowledge was the primary focus of their conversations.

Twitter polls are not scientific studies and have some biases built into them. And of course, some emotional topics also impart knowledge. Nonetheless, the outcome sits nicely with the sex differences in systemizing and empathising long known by cognitive and developmental psychologists which reflect different selection pressures on men and women over evolutionary history. There’s also a corpus of classical research finding sex differences between the conversational content of same-sex friends.

A failure of cross-sex mind reading

I could write a whole book on whether it’s right or wrong that male and female same-sex conversations have these leanings but, for better or worse, men build same-sex relationships in qualitatively different ways to women.

This can present a problem when men try to grow closer to women as friends, work colleagues, and intimate partners. People have a tendency to assume that others are like them and men often say they struggle with nuanced social skills like flirting. Together, it makes it more likely that men will use their experience in building relationships with other men to inform how they approach women. The result can be systemising, knowledge-imparting conversations.

The least charitable interpretation of this is that it’s done intentionally and with malice to put women down. But I favour a more balanced view, that it’s a failure of cross-sex mind reading, a failure to judge the style of conversation that women will like when building relationships with others.

It’s a view born from the idea that people are generally good and seek to avoid upsetting others, especially those to whom they want to become closer. Ironically, this view implies that allegations of mansplaining may also be a failure of cross-sex mind reading by assuming that the motive of men imparting knowledge or talking about practical things is to harm women.

The impact on forming relationships

All of this, of course, has implications for getting things off on the right foot with someone and forming the foundations of a romantic relationship. We can enhance our ability to make a connection with another person by recognising that their communication style might be different from ours. In the case of men, that means anticipating that women might be expecting a more balanced mixture of emotions and knowledge. And for women, it’s understanding that, in a large number of cases, what may look like mansplaining on the surface might be a signal that a man genuinely cares about cultivating a relationship, but is simply trying to do so in a way he’s used to.

References

Aries, E. J., & Johnson, F. L. (1983). Close friendship in adulthood: Conversational content between same-sex friends. Sex roles, 9, 1183-1196.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2007). The evolution of empathizing and systemizing: Assortative mating of two strong systemizers and the cause of autism. In L. Barrett & R. Dunbar (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 213–226). Oxford University Press.

Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error management theory: a new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(1), 81.