Artificial Intelligence

Colleges Experiment With AI Classmates

If your classmates aren't real, here are some deeper questions to ask.

Updated January 10, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- A new experiment in higher education is to insert virtual students into online and hybrid courses.

- The practice is similar to using non-player characters (NPCs) in video games and digital worlds.

- NPCs can help video games feel more lifelike and realistic because they encourage social presence.

- We do not know if classroom NPCs would have similar effects, and there are concerns about adverse outcomes.

Recently, Ferris State University caught headlines with a pair of students enrolled for spring 2024: Ann and Fry. Normally, new student enrollments hardly attract attention and media scrutiny.

What makes these two unique? They're not humans in a biological sense but rather virtual students created by the university to attend hybrid courses, "where they'll interact with classmates and complete assignments," among other things. According to press releases, this program is part of Ferris State's investments in artificial intelligence (AI) broadly.

For a media psychologist, however, this program raises some curious questions—and again points to the relevance of scholarship on video games.

Virtual Agents Enrich Video Games

Enrolling virtual students in hybrid courses reminds me of the role that non-player characters (NPCs) play in video games. For many video games, part of their appeal is that they provide players with social realities: Rich digital worlds with elaborate and emotionally engaging narratives populated by characters with their backstories and struggles.

When players reflect on meaningful gaming experiences, they tend to focus on narratives and their social relatedness with those NPCs. Some refer to this as a eudaimonic entertainment experience focused on personal reflection and emotional engagement. Many have argued that contemporary video games have grown from a single (albeit very exciting) focus on hedonic enjoyment to presenting players with more emotionally complex narratives.

One reason that these NPCs are so critical to gaming experiences is that they provide players with a sense of social presence. The concept was originally introduced by Short et al. (1976), and it refers to having a sense of being with others when communicating through a technological medium. The concept was later refined to focus on digital worlds, such as those provided by video games and virtual reality technologies (Lombard and Ditton, 1997).

Research has shown that when NPCs are more autonomous (for example, appearing to make decisions on their own), players feel higher levels of social presence (Brandstätter and colleagues, 2021). In some cases, players might be able to literally see digital worlds through the eyes of NPCs, which can increase psychological closeness with and empathy towards those social others (Ho and Ng, 2022). Others, such as Schumann and colleagues (2016), found that presence was associated with NPC interactions were seen as consequential for the experience unfolding—similar to games such as Detroit: Become Human in which player-NPC dialogues result in branching narratives, social, and emotional consequences (Holl and Melzer, 2021).

Virtual Students in a Community of Inquiry

Coming back to Ann and Fry, one way we can understand their enrollment as Ferris State is similar to NPCs in video games. From media reports, the students were given "backstories, created by faculty members, based on real student experiences." This is not too dissimilar to elements of NPCs mentioned above that facilitate social presence.

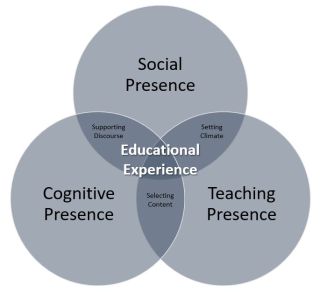

Indeed, parallel research in hybrid education suggests that online courses greatly benefit students when they feel a sense of social presence with their classmates and instructors, in research derived from Garrison and colleagues' (1999) community of inquiry model.

On the surface, I can see where including virtual students in an online classroom could help benefit the overall experience. If those students provide a sense of social presence for others, it could encourage the supportive discourse necessary for learning content while helping set a social and receptive tone for instructors teaching the content. Especially for live courses, these could help combat the very real negative side-effects of Zoom fatigue.

At the same time, there could be some equally real (and quite negative) side-effects of seeding courses with virtual students. For example, I wonder what would happen to social presence if students were acutely aware of their virtual colleagues or if they felt as if they had been "catfished" after otherwise bonding with students throughout a semester.

Notably, in video games, players are aware that NPCs are not sentient social beings, yet we still bond with those characters. That said, there are likely expectations of human interactions in online courses that are quite different than expectations of NPCs in gaming and digital worlds.

From an academic perspective, and depending on how these virtual students are controlled, there's also concern about the quality of the students' engagement. Despite the fear and fanfare around generative AI programs such as ChatGPT, experience shows us that AI programs produce pleasant-sounding but otherwise mediocre (often incorrect) homework answers, according to National Public Radio.

At best, Ann and Fry might make nominal contributions to classroom discussions, but at worst, they might also replicate and spread known racist and misogynist content. That's not to say that human students don't engage in the same behaviors, but the problem is confounded when the institution itself introduces it.

We might also wonder how virtual students will be expected to react and behave when they witness misbehavior, such as students engaging in academic dishonesty. Perhaps it is an extreme case, but we could wonder what ethical guidelines should be used when those faculty supervising virtual students come across evidence of more insidious behaviors, such as academic bullying, hazing, or even sexual or domestic violence. In most circumstances, faculty and staff are mandatory reporters of such behaviors.

Finally, there could be a concern that institutions are using virtual students to engage in surveillance activities, monitoring teachers, students, and content in ways that could be harnessed toward a variety of endgames. Such fears are increasingly salient to faculty teaching in states that are outwardly hostile towards higher education, such as passing legislation limiting discussions of critical race theory (broadly defined).

Having Fun, But a Bit of Caution

The scenarios outlined above could be viewed as a moral panic. Still, there are notable cautions that should be considered in the race towards improving student experiences on college campuses, hybrid or otherwise. Perhaps there is more to the story, and I would be fascinated to see companion scholarship on the student and faculty experience. That said, I question what could be seen as an extreme case of gamification: Creating NPCs to populate classes to inflate the social experience.

The notion of a virtual student is hardly new for Georgia Tech students and George P. Burdell's classmates. I even remember when user error (for example, I filled the application out wrong) resulted in both Nicholas David Bowman and David Nicholas Bowman being accepted to college. The Harvard Crimson likewise provided a rich history of fake students attending the prestigious institution. Those efforts continue to provide hilarious anecdotes and campus legends.

I am curious to see how Ann and Fry are received by their classmates.

References

Annand, D. (2011). Social presence within the community of inquiry framework. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ963922.pdf

Bailenson, J. N. (2021). Nonverbal overload: A theoretical argument for the causes of Zoom fatigue. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000030

Brandstätter, P., Sagmann, S., Krükel, D., Maurer, M., & Lankes, M. (2021). I will stand by you: Measuring the perceived Social Presence towards Semi-Autonomous Companions in a 2D game. Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Austria, 5-9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3450337.3483488

Edwards, C., Edwards, A., Spence, P. R., & Westerman, D. (2016). Initial interaction expectations with robots: Testing the human-to-human interaction script. Communication Studies, 67(2), 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2015.1121899

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Ho, J. C. F., & Ng, R. (2022). Perspective-taking of non-player characters in prosocial virtual reality games: Effects on closeness, empathy, and game immersion. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(6), 1185-1198. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2020.1864018

Holl, E., & Melzer, A. (2021). Moral minds in gaming: A quantitative case study of moral decisions in Detroit: Become human. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000323

Liszio, S., Emmerich, K., & Masuch, M. (2017). The influence of social entities in virtual reality games on player experience and immersion. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (FDG), USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/3102071.3102086

Lombard, M., & Ditton, T. (1997). At the heart of it all: The concept of presence. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x

Oliver, M. B., Bowman, N. D., Woolley, J. K., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B., & Chung, M-Y. (2015). Video games as meaningful entertainment experiences. Psychology of Popular Media and Culture, 5(4), 390-405. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000066

Schumann, C., Bowman, N. D., & Schultheiss, D. (2016). Quality in video games: Subjective quality assessments as predictors of self-reported presence in first-person shooters and role-playing games. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 60(4), 547-566. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2016.1234473

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. Wiley.