Trauma

What Is Complex PTSD?

Identifying CPTSD and its shame-based roots.

Posted August 27, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Diagnostic criteria for complex PTSD include affect dysregulation and a negative self-concept.

- Unlike PTSD, flashbacks associated with complex PTSD may not have a strong visual or auditory component.

- It is possible to be stuck in a trauma response for decades and consider it to be "normal."

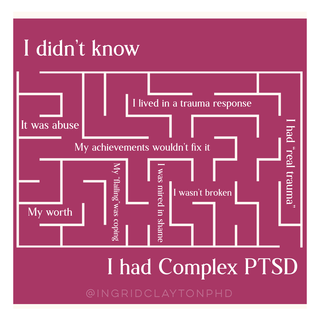

I have been working on my emotional sobriety, in recovery from addiction and codependency, for 26 years. I’ve been in therapy longer than that. I’ve done yoga, read the books, and even built a private practice as a psychologist helping people regulate their own emotions. But in some ways, I’ve felt like it was all just a whack-a-mole game. Nothing ever fixed the feeling that I was intrinsically broken.

I always knew I had trauma in a colloquial sense. I could tell you, “I experienced childhood trauma.” But I didn’t think it was real trauma. I thought I needed a worse story to be as deeply impacted as I’d been, so my “symptoms” were mine alone. My problem was my Ingridness.

- I was in recovery for addiction.

- Another program for co-dependency.

- Soaking up Brené Brown to navigate my shame.

- Exercising and doing yoga to manage my hypervigilance.

- Engaged in spiritual practices.

- Getting continual training as a psychologist.

- Working in therapy on anxiety and my lack of self-worth.

But I felt fragmented, like all of these pieces were locked off in separate quadrants from one another. I felt like I was in constant management of me, striving rather than healing.

As a therapist, I understood that trauma was less about a particular event and more about how its effects play out in our nervous system. Trauma is the story we hold in the body and the way it defines our present moment. So, I was personally utilizing EMDR and Somatic Experiencing (highly effective treatments for trauma) with my clients. I was talking about complex trauma (developmental/childhood/attachment trauma) almost every day. And yet I still didn’t know the extent to which I identified with the typical pattern of symptoms. I could see them for the people I was working with, but I’d been managing mine for so long, I was disconnected from how my own story lived and breathed in my cells—changing their very nature.

I think some of my personal confusion was rooted in the mental health communities’ confusion about complex trauma. Despite decades of trying to get a diagnosis in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) in the United States, a discrete diagnosis from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) has yet to be included.

It was only recently that the ICD-11 (WHO’s International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision) captured the intricate picture of complex trauma in their diagnosis: complex PTSD or CPTSD.

It shares similar criteria with PTSD, including:

- Reexperiencing traumatic events (nightmares, unwanted memories, flashbacks)

- Avoidance of traumatic reminders (people, places, feelings, thoughts)

- A persistent sense of current threat (hypervigilance)

But it extends beyond these to include:

- Affect dysregulation

- Negative self-concept

- Disturbances in relationships (typically associated with sustained, repeated, or multiple forms of traumatic exposure)

With complex trauma, there is a distortion in a person’s core sense of self. Additionally, PTSD is often related to a single event, whereas CPTSD includes repeated traumatic events, often in childhood.

To receive a diagnosis of CPTSD, a person must have at least one symptom from each of the six categories as well as exposure to at least one traumatic event.

I had previously wondered if I had PTSD as it related to my upbringing but the very question inspired deep shame. A fundamental experience in my house as a child revolved around gaslighting: psychological manipulation designed to make someone question their own reality. I constantly wondered:

Did all of that actually happen? And if it did, was it that big of a deal?

I also thought I didn’t qualify for a diagnosis of PTSD because I’d never had a flashback. I thought they were all like the ones we see in the movies, with a specific memory, strong visual and auditory component.

It turns out, flashbacks are defined as any way we reexperience our traumatic past as though it’s happening right now. And emotional flashbacks are a core feature of CPTSD. Pete Walker, a psychotherapist who specializes in complex trauma, refers to emotional flashbacks as “sudden and often prolonged regressions ('amygdala hijackings') to the frightening and abandoned feeling-states of childhood.”

I’d been living in an emotional flashback for decades.

When I was growing up, my narcissistic stepfather would cycle between the silent treatment, giving me praise, and becoming a predator. My nervous system was on constant high alert.

To this day, when I’m trying something outside of my comfort zone or I don’t know something in advance, it can ignite my shame response. When I get positive or negative feedback, it can ignite my fraud or imposter syndrome response. There are many others I could mention, but the key to these flashbacks is that they weren’t tied to a specific memory, so I never recognized them as flashbacks at all. They felt solely related to a current event. They just felt “real.”

I am bad, I am a loser, everything is about to fall apart.

In addition to experiencing emotional flashbacks, my relationship history was, shall we say, complicated. My chemistry only kicked in if a guy had one foot in the door (maybe a toe) and I was trying to win him over. He was often an active addict, had a personality disorder, or both. I was repeatedly reenacting my abusive past hoping for a different ending. Proving myself was the goal for so long, I never knew it could change.

In terms of hypervigilance, even as a grown woman, I’ve often felt like I’m about to get in trouble. For a million different reasons, it feels like I am going to receive steep punishment at any moment and I have to guard against it. It’s exhausting. I’ve become a perfectionist—trying to achieve enough success to save me. But it never does.

All of these things combined have woven a deep pattern of fixity in my body, a confusing relationship to myself and my environment, an underlying anxiety that talk therapy could never mend. But several years ago, I started to write my own story. I began to see it from a different perspective. All of the fragments were coming together.

I could see how I’d been stuck in a trauma response for decades and it just seemed “normal.” I could understand how I never “got over it” with traditional psychotherapy or my recovery from addiction. “Moving on” or “forgiveness” wouldn’t have felt authentic and would have left me abandoned by the one person who could’ve saved me: myself.

I couldn’t move on until I’d processed and integrated everything that had happened, and that meant going back. I had to reclaim the parts of me that had been left behind. My whole life, I’d been looking outside of myself for an enormous, clear, undeniable victory over my obvious dysfunction. I was constantly trying to overcome. But when I finally acknowledged that I had actual pain for actual reasons, I became a real live person, flooded with feeling. I wasn’t alone anymore. It wasn’t just me.

I stopped saying, “maybe it wasn’t that bad,” and started trusting myself. I’d previously been focused on “them” believing me, believing everything that had happened. But they never gave me that validation. And that’s okay. I no longer wonder what happened to me. I’m not confused as to why I became addicted, codependent, and riddled with angst. I finally see the big picture, and it all makes sense.

Today, I believe we are in the midst of a collective awakening as generations are coming to terms with how their own traumas have impacted their lives. Dr. Bessel van der Kolk’s book, The Body Keeps The Score (a foundational text in trauma recovery) was released in 2014. It has been on The New York Times Best Seller List for the last 148 weeks and is currently number one for paperback nonfiction.

There seems to be a hunger to understand something that has felt so elusive, and led to so many feelings of “brokenness” for so long. Despite the DSM-5’s omission of CPTSD, I see the tides turning. We are reclaiming our stories and our nervous systems. We are becoming more and more grounded in present time and place, inhabiting our own bodies with love and compassion. We are setting healthy boundaries and choosing healthy partners and friends. We are refusing to just “get over it” and are shedding the negative beliefs that never belonged to us anyway. We are actually getting free.

*If you think you might have complex PTSD or are looking for tools for trauma recovery, please see a medical/mental health professional who specializes in trauma. The above examples are Ingrid’s personal experience with CPTSD and not a comprehensive picture of how complex trauma is experienced for everyone.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en