Intelligence

The Innate Intelligence Observed in the Dying Process

Reframing death as an inherent corporeal intelligence.

Posted March 2, 2023 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- In the majority of dying situations, the dying person’s lingering is related to them alone and has nothing to do with their needs from others.

- The dying process has an ancient intelligence that is as old as life itself and needs nothing from the outside world in order to function.

- Those who are dying are immersed in their own world, and rarely if ever seek "permission" from others.

Sandra came out of the homelike room where her dad lay, now comfortable, dying. He hadn’t eaten or drunk anything for several days now, and, although he was restless a day ago, he was now quite comfortable. He was, as we say in hospice, actively dying.

From my perspective, he was exactly where he was supposed to be, peaceful, his body appearing at ease, breathing comfortably, eyes closed, belly flat, extremities motionless with an air of calm certainty that portends the probability of a “good death.” However, Sandra appeared the polar opposite of her father. She was heartbroken, grieving, and troubled by what she was seeing, and I wanted to know why.

Permission to Go

We talked outside the room as she described the guilt she felt toward her dad. She was in tears. “I’ve told him that he can pass, that he can move on and leave at peace. 'We’ll be fine,' I said, 'Dad, please don’t worry about me or my sister…you can go,'” as her tears continued to flow, “'But don’t wait for us.' I was giving him permission to go, to leave his body and leave this world, but, despite my pleading and reassurance, he keeps on living like this," she tells me. "He’s not living or dying but just 'hanging on,' and I don’t understand for what? Why can’t he just pass!” as Sandra starts to cry profusely with her head solemnly down in agony and confusion.

I understood where she was coming from and have been giving this some thought lately as she wasn’t the only relative who had felt the anguish of guilt for taking responsibility for a loved one’s not passing. The issue, as I see it, is a cultural/spiritual and loving thought within popular consciousness that has gained a significant following among those who are in the midst of losing a loved one. I don’t want to disparage the concept, as I’m sure there are those moments when a verbal release from a loved one is all that’s required for one to pass. Still, in the majority of dying situations, the dying person’s lingering is related entirely to them alone and has nothing to do with their needs from others.

My intended goal is to allow those family members who deeply care about their loved ones to be released from their agony and be absolved of their responsibility for their loved ones dying. It is my belief and observation that the dying process has an ancient intelligence that is as old as living itself and needs nothing from the outside world in order to function.

An Innate Intelligence

We typically refer to intelligence as “intellect” to denote a conscious ability to use the mind via analysis, thought, and perception. We can even say that we can train our minds to improve our ability to discriminate, analyze, and process data to increase our mental bandwidth so that our minds can continue to evolve to an ever-higher capacity. Perhaps such a mind may be distinguished as smart or brilliant. That type of intelligence is definitely sought, and many of us want to improve our ability to use our minds, but the intelligence that I want to discuss is far removed from the conscious ability of using our intellect for a purpose. The intelligence that I perceive in those that are dying is an innate capacity that the body has developed over eons of births and deaths as living biological beings.

A just-born infant has no ability to consciously process information. That processing develops much later, but what an infant is able to do is rely on hereditary instinct that takes possession of its fledgling mind and body for the purpose of launching it into life. The intelligence that I refer to is the ingrained genetic programming that makes the infant take its first breath, cry, shiver, quiver its arms and legs, and turn its head toward the breast to take its first meal. We have in our culture relegated this intelligence to the medicalized word “reflex,” but we should not be so cavalier in reducing the impact of an innate program within a living being to a mere “reflex.”

What we observe in a reflex is the profound and innate intelligence as it manifests itself immediately at the start of an infant's life. I posit that the innate intelligence seen in a newborn is just an example of the profound impact of that intelligence during the life cycle. The body's innate intelligence is responsible for the various physiological systems, such as the nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, and digestive system, all of which are critical to preserving life. By extension, there is no reason to believe that that same intelligence is not present at our death, at the finality of life’s procession.

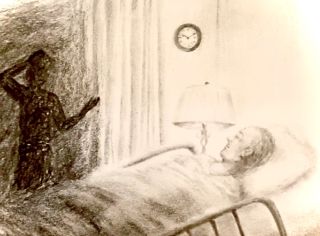

I have been privy to many deaths as a physician who works in hospice and have witnessed the dying process many times, and, although individual variation exists, of course, there is a definite pattern that can be observed. People become inexplicably exhausted and socially withdrawn—signs that point to an inward process of the body shutting down. Appetite diminishes and then disappears completely due to a complete lack of interest in sustenance. Unless there is agonizing pain, shortness of breath, or delirium, the body goes further inward by tending to prefer sleep much more than being awake.

As the dying process progresses, the body’s physiologic changes become manifest. Breathing becomes erratic, urination stops, and skin color changes as well. The body’s need for sleep completely engulfs consciousness as the mind and body descend to their final voyage home. The body surrenders to the intelligence of death. Death is in control now. The archaic intelligence of death has taken over.

Experiencing a loved one’s dying process is a deeply intense emotional experience, one that leaves an indelible impression on the heart and mind. Sometimes in the active phase of dying, the person lingers in time longer than what you consider acceptable. It’s natural to wonder why, raising the possibility that he who is dying just needs permission to let go. If you have given that permission and they still linger, don’t make it about you. Let yourself off the hook. It’s not your fault. He who is dying is immersed in his/her own world guided by an innate intelligence of the dying process. It is recommended to respect their journey by allowing them to go through it on their own terms.