Relationships

What Does "Love" Mean?

New research shows there may be many different 'flavors.'

Posted February 14, 2019

As Valentine’s day rolls around again, many people’s thoughts will be turning to love, whether in celebration of enjoying it or the hope of finding it. But what is love? It’s easy to be misled into thinking that it revolves around the star-crossed tale of falling romantically ‘in love.’ But love is far more varied and multifaceted than that. In fact, few words span a wider range of feelings and experiences than love.

I call upon it for the deep ardor, care and respect I have for my wife, and moreover, I apply it consistently to our bond across the day-to-day ephemera of shifting moods. It also fits the unshakable bonds of kinship and history I share with my family, and the allegiances I find with close friends. But I also consciously use it in relation to myriad other phenomena, including our little dog Daisy, swimming outdoors, summer music festivals, hot chocolate, and much more besides.

Styles of love

Evidently, whatever love is, it encompasses a great deal of emotional and experiential territory. I’m not the first to notice this of course. In the 1970s, for example, John Lee1 inventively drew upon the classical lexica of Greek and Latin—which developed a wealth of words for specific kinds of love—to identify six different ‘styles.’

He identified three primary forms of love: eros (passion and desire), ludus (playful or ‘gameful’ affection), and storgē (familial or companionate bonds of care). By pairing these, he generated three secondary forms: pragma (a sensible negotiated partnership, combining ludus and storgē), mania (possessive, dependent, or troubled intimacies, combining eros and ludus), and agápē (charitable, selfless compassion, combining eros and storgē).

An alternative theoretically-derived typology was developed by Robert Sternberg2. His ‘triangular’ theory of love suggested love arises from the presence and interaction of three principal components: intimacy, passion, and decision/commitment. Their permutations then give rise to seven types of love: liking (intimacy alone); infatuated love (passion alone); empty love (commitment alone); romantic love (intimacy and passion); companionate love (intimacy and commitment); fatuous love (passion and commitment); and consummate love (all three).

These analyses add further nuance to our conception of love. However, they remain incomplete. For a start, they pertain only to romantic partnerships. They, therefore, fail to capture many of the feelings and connections that fall within the ambit of ‘love’ in popular discourse. To remedy this, I sought to construct a more detailed typology of love, one reflecting its polyphonous nature. My method in that respect was the relatively unusual device of exploring ‘untranslatable’ words relating to love.

A linguistic search for love

This exploration sits within my broader ongoing lexicographic project to collect untranslatable words which pertain to wellbeing (i.e., words lacking an exact equivalent in one’s own language, in my case English). This is a work-in-progress which currently features over 1,000 items. Such words are significant, for many reasons. They signify phenomena which one’s own culture has overlooked, but which another culture has identified and conceptualised3. As a result, they assist us in understanding other cultures, offering insights into their values, traditions, and ways of being4. Moreover, they can give people new concepts with which to articulate and understand their own experiences; for that reason, such words are frequently ‘borrowed’ by other languages, as they fill a ‘sematic gap’ in that language5.

I began the collection in 2015 and published an initial analysis of 216 words in 20166. Since then, the list has expanded to over 1,000 words, assisted by generous suggestions from people around the world. My approach has been to analyze the words thematically, using an adapted form of grounded theory, in which theory is inductively derived from data by examining emergent themes7. Through this, I identified six broad categories of words, and have since conducted specific analyses in relation to each, namely: positive emotions8, ambivalent emotions9, character10, spirituality11, prosociality12, and—most relevantly here—love13. With respect to each of these arenas of experience, untranslatable words can enrich our knowledge and appreciation of them. In the case of love, then, such words help us understand the bountiful variety of emotions and bonds that are in English subsumed within the one word ‘love.’

The flavors of love

My inquiry yielded hundreds of words, which I analyzed thematically and published last year in the Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour14. I grouped these words into 14 distinct ‘flavors’ of love—which, in a spirit of poetic consistency and in a nod to John Lee’s influential theorizing, I gave a relevant Greek label. I call these ‘flavors’ to avoid implying that relationships can be exclusively pigeon-holed as constituting just one form. A romantic partnership might blend several flavors together, generating a unique ‘taste’ which might evolve subtly with time.

What are these flavors? The first three do not concern people at all, nor do they involve romance. That is, we can speak of people’s fondness and passion for certain activities (meraki), places (chōros), and objects (eros). (Unlike John Lee’s typology, where eros signified a desire for people specifically, its deployment here reflects its usage in classical Greece, where philosophers often invoked it the context of aesthetic appreciation more generally rather than romance per se.) Then, having checked these boxes, the analysis delves into the myriad forms of love we can hold towards people.

The first three are non-romantic forms of care, affection, and loyalty we extend toward family (storgē), friends (philia), and ourselves (philautia). Then, embracing the arena of romance, Lee’s notions of pragma, mania, and ludus—the latter labeled here using its Greek cognate paixnidi—are joined by the passionate desire of epithymia and the star-crossed destiny of anánkē. Finally are three forms of selfless ‘transcendent’ love, in which one’s own needs and concerns are relatively diminished: The compassion of agápē; ephemeral sparks of connection, as denoted by koinonia; and the kind of reverential devotion that religious believers might hold toward a deity, known as sebomai.

The components of love

This typology of flavor expands upon the theorizing of Lee and Sternberg, who offered relatively limited conceptualizations. One possible reason for their limited scope is that their models were formulated on the basis of only three primary components—components which tend to be present in romantic love—namely, eros, ludus, and storgē in Lee’s model, and intimacy, passion, and decision/commitment in Sternberg. However, there is no a priori reason that love should only comprise three such components.

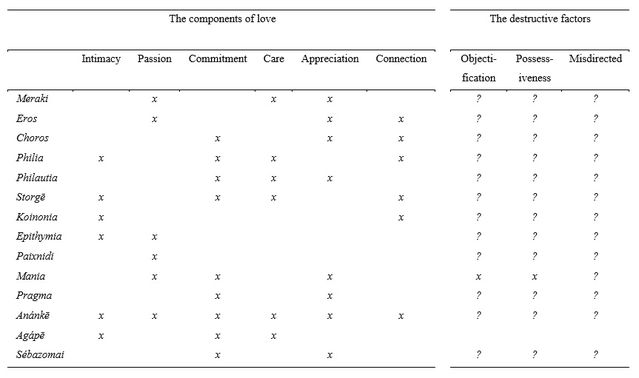

Indeed, it was possible here to identify three further candidates that warrant the status of primary components (in that their presence alone might still merit the use of ‘love’): care; connection; and appreciation. I might love a new song that I hear, for example. This feeling is not characterized by Sternberg’s components of passion, intimacy, or commitment, but by aesthetic appreciation. As such, I have made a preliminary attempt to categorize the 14 types of love according to six primary components: Sternberg’s trio of passion, intimacy, and commitment, plus care, connection, and appreciation—as outlined in the table below. It also reflects the possibility that nearly all forms of love potentially have a destructive ‘dark’ side, including that the focus of a person’s love may be, (a) objectified in some way, (b) treated with possessiveness, and (c) ‘misdirected' according to prevailing morals and norms.

A work-in-progress

It must be noted that the analysis above is only provisional. The assignation of components in the table is merely hypothetical at this stage. It is based on a close reading of the words that helped create the category, together with reflections based on personal experience. Future research will be required to substantiate or otherwise refine these assignations. Relatedly, the 14 types of love identified here are not necessarily exhaustive. Indeed, given that Sternberg’s three primary components gave rise to seven possible permutations, with six primary components, the number of theoretical combinations rises to 63! Without implying that there are 63 different types of love, it is possible that other forms of love remain to be identified. Indeed, it is hoped that my research will provide the stimulus for just such a research program, aiming to both better understand the 14 types identified here (e.g., in terms of how they load on the six hypothesised components) and to ascertain whether they should be joined by any other distinct types.

At the very least though, clearly there any many ways we can love and be loved. So hopefully we can be reassured, with Valentine’s day in mind, that even if one is are not romantically head-over-heels ‘in love’ in that archetypal Hollywood fashion, our lives may still be graced by love in some precious and uplifting way.

References

[1] Lee, J. A. (1977). A typology of styles of loving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3(2), 173-182.

[2] Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93(2), 119-135.

[3] Lomas, T. (2018). Experiential cartography, and the significance of untranslatable words. Theory & Psychology, 28(4), 476–495.

[4] Wierzbicka, A. (1997). Understanding Cultures through Their Key Words: English, Russian, Polish, German, and Japanese. New York: Oxford University Press,.

[5] Lehrer, A. (1974). Semantic fields and lexical structures. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co.

[6] Lomas, T. (2016). Towards a positive cross-cultural lexicography: Enriching our emotional landscape through 216 ‘untranslatable’ words pertaining to wellbeing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 546-558.

[7] Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociological Press.

[8] Lomas, T. (2017). The spectrum of positive affect: A cross-cultural lexical analysis. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7(3), 1-18.

[9] Lomas, T. (2018). The value of ambivalent emotions: A cross-cultural lexical analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2017.1400143

[10] Lomas, T. (2018). The roots of virtue: A cross-cultural lexical analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-9997-8

[11] Lomas, T. (2018). The dynamics of spirituality: A cross-cultural lexical analysis. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. doi: 10.1037/rel0000163

[12] Lomas, T. (2018). The dimensions of prosociality: A cross-cultural lexical analysis. Current Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-0067-5

[13] Lomas, T. (2018). The flavours of love: A cross-cultural lexical analysis. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 48(1), 134-152.

[14] Lomas, T. (2018). The flavours of love: A cross-cultural lexical analysis. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 48(1), 134-152