Sex

Sliding Scales of Biological Sex Characteristics

Multiple axes describe people better than binary sex categories or a spectrum.

Posted January 3, 2023 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Biological sex characteristics are multidimensional and therefore require multiple axes or sliding scales to represent them accurately.

- Even primary sex characteristics, like gonads and genitals, are better represented with sliding scales.

- Sliding scales can also be used to describe secondary sex characteristics like height, musculature, body hair, voice pitch, and facial structure.

A traditional view is that, biologically, there are exactly two sexes, and each person can be accurately described as simply female or male. This is often called a binary view of sex. This view is still common, but for many people, their biological characteristics do not match this description.

Sex and Gender Spectrum

Another view that is currently popular in the queer community is that sex and gender each exist on a spectrum, akin to the colors that collectively compose white light, from red through yellow, green, and blue, to violet. This idea is most often presented for gender—feeling or acting feminine or masculine or in between. But this concept is also sometimes used to describe sex—our biological features related to reproduction. The essential idea of the spectrum is that our gender- or sex-related features vary continuously along a single axis of a graph, running from extreme femininity at one end to extreme masculinity at the other end.

The idea of a sex/gender spectrum is much more expansive than binary categories. But if you identify at some location along this spectrum, this means that all your features come as a package—if you are feminine in one way, you are feminine in all ways. In this view, each person’s sex or gender can be defined by a single point along one axis.

An example of this view comes from Simon LeVay, a neuroscientist and author who provided evidence in a 1991 Science article that there is a brain region (within the hypothalamus) that is largest in straight men, smallest in straight women, and intermediate in gay men. He also argued in his book, Gay, Straight, and the Reason Why, that a whole set of brain and personality characteristics are correlated and that gay people (including himself) are intermediate between straight men and straight women on all these characteristics. Thus, in his view, one axis is sufficient to describe a person’s sex, gender identify, and sexual orientation.

Sex and Gender Mosaics

But most people’s biological and psychological characteristics vary tremendously. They may be more typically feminine for one characteristic, more typically masculine for another, and intermediate for a third. If so, their sex cannot be defined by a single axis. It requires multiple axes, perhaps dozens.

This point has been made persuasively by Daphna Joel, a psychologist and neuroscientist at Tel-Aviv University. In several studies, especially in a 2015 article in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and later in a book, Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain, she used large human brain-imaging databases to demonstrate that most people’s brains have some features that are more typically feminine, others that are more typically masculine, and still others that are intermediate. Thus, she describes the brains that most people have as mosaics. Joel argues that this mosaic metaphor matches data from both brain imaging and a variety of psychological tests better than either binary categories or a spectrum. She contrasts our brain and psychological traits with our genitals, which she argues can be described relatively well as either female or male.

Joel’s idea is essentially that one axis cannot describe all our sex- or gender-related brain and psychological characteristics accurately; instead, many axes are needed. For example, there would be one axis—running from small to large volume—for brain region A, another such axis for brain region B, and so on. If brain regions A and B are both larger in women than men on average, one person may have a relatively large region A but a relatively small region B, while another has a relatively small region A but a relatively large region B. In this case, we can’t say that one of these people is more feminine or masculine than the other—it depends on which brain feature we focus on. When there are multiple, independent axes like this, we can say there is a multidimensional space created by all these axes together. Joel argues that each of us occupies a unique location within this multidimensional space.

Sliding Scales of Sex Characteristics

A more familiar and intuitive way for most people to think about these multiple axes might be by using several sliding scales, which most of us are familiar with from online surveys. With sliding scales, you can move the slider to any location along each axis, such as from strongly disagree to strongly agree:

I suggest that we indicate our biological sex characteristics using multiple, independent sliding scales. I also suggest that sliding scales can represent a wide variety of biological sex characteristics more accurately than either binary categories or a single spectrum, not only for brain and psychological characteristics but also for many other sex-related biological characteristics, including anatomical features that most people think are always simply female or male.

Primary sex characteristics are those directly related to reproduction. They include chromosomes—the sets of genes that direct the development of our gonads; gonads—the ovaries that make egg cells in typical females, the testes that make sperm cells in typical males; and external genitals—the clitoris and labia for typical females, the penis and scrotum for typical males. Secondary sex characteristics are not directly related to reproduction but on average are correlated with being female or male; they include height, musculature, body hair, voice pitch, and facial structure.

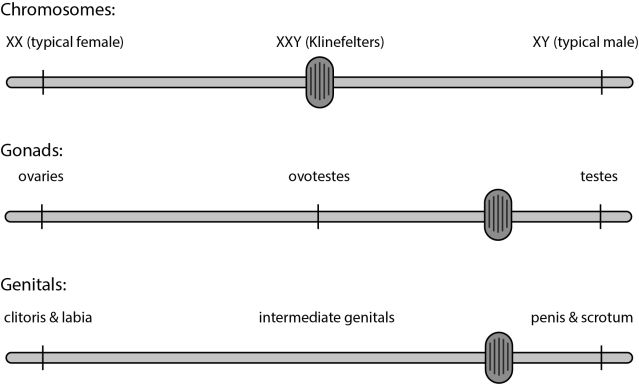

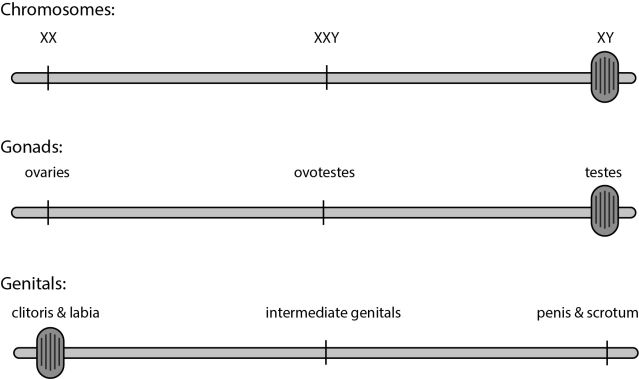

To illustrate the idea of multiple sliding scales for sex characteristics, let’s take a few examples involving primary sex characteristics. In each example, we’ll use three separate sliding scales—one each for chromosomes, gonads, and genitals. If this works for primary sex characteristics, it should certainly work for secondary sex characteristics as well.

Klinefelters

Typically, females have two X chromosomes (i.e., are XX) and males have one X and one Y chromosome (i.e., are XY). But some people are XXY (Klinefelters). They can be thought of as having intermediate chromosomes. Their sexual organs, however, are more typically masculine than feminine, as they have testes and a penis, though both are usually smaller than in a typical male. Here is a version of the three sliding scales for someone with Klinefelters:

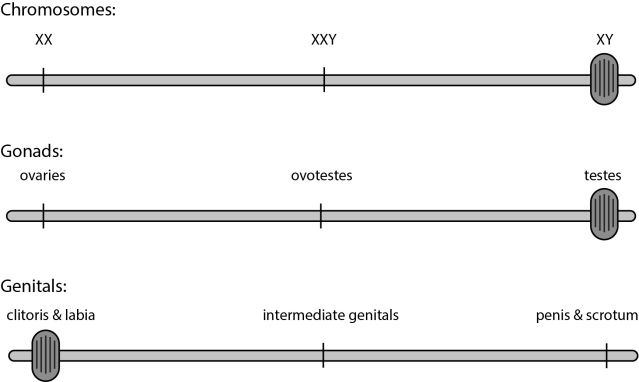

Androgen Insensitivity

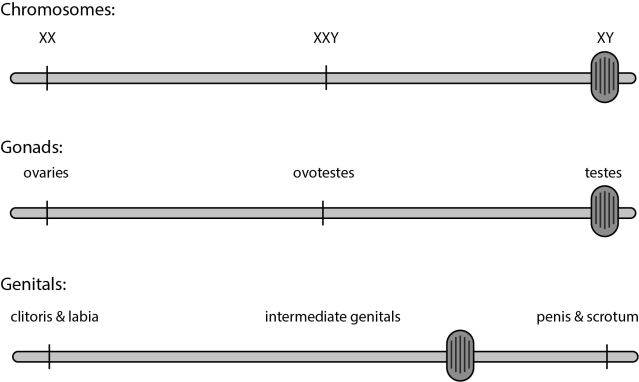

Other people are XY and have testes but have no response to the androgens (often called “male sex hormones”), including testosterone, that their (internal) testes produce—they have complete androgen insensitivity. We all began with the same kind of undefined genital tissue that then developed prenatally into either a clitoris or a penis or an intermediate structure. Similarly, we all began with undefined tissue that developed prenatally into labia, a scrotum, or an intermediate structure. In the presence of androgens, a fetus develops typically male genitals—penis and scrotum—and in the absence of androgens (or with androgen insensitivity), a fetus develops typically female genitals—clitoris and labia. As a result, XY people with complete androgen insensitivity have genitals (as well as secondary sex characteristics) that are typically female:

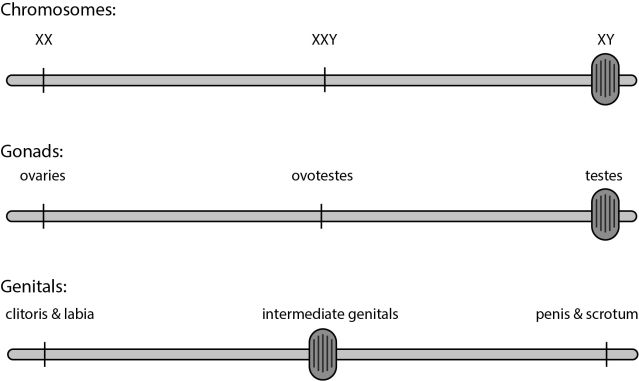

Still other people are XY and have partial androgen insensitivity. They usually have genitals that are intermediate between a clitoris and a penis and intermediate between labia and a scrotum:

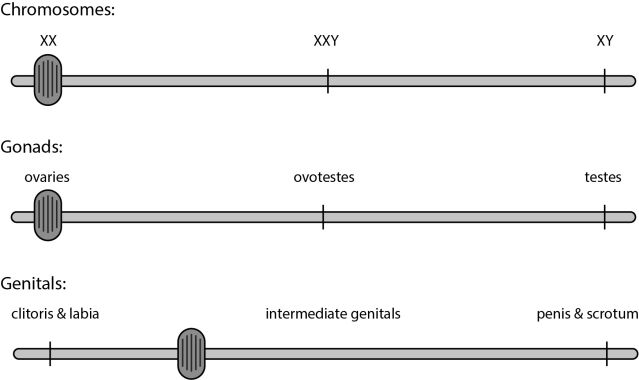

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

There are also people who are XX and produce extra androgens from their adrenal glands (congenital adrenal hyperplasia). They have ovaries instead of testes, but the extra androgens from their adrenals “masculinize” their genitals, which are often intermediate between typically female and typically male:

About 1.5 percent of people, or about 5 million people in the U.S., have congenital adrenal hyperplasia.1

5-Alpha-Reductase Deficiency

Still other people are XY but make a less functional form of an enzyme that converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, which is more important than testosterone in shaping the genitals prenatally (5-alpha-reductase deficiency). These people are born with (internal) testes but female-typical genitals:

With the surge in testosterone at puberty, their genitals transform in a male-typical direction, to a degree that depends on how well the 5-alpha-reductase enzyme works. In a community in the Dominican Republic where this condition is common, it was named “guevodoces,” usually translated as “penis at 12” (but more precisely as “eggs at 12,” as the testes descend into the scrotum then). Thus, following puberty, one of these sliders effectively moves:

It should be clear from these few examples that multiple, independent axes—sliding scales—best represent biological sex characteristics for many people, even for chromosomes, gonads, and genitals.

If this is true for primary sex characteristics, it is even more true for secondary sex characteristics, such as height, musculature, body hair, voice pitch, and facial structure. Independent, sliding scales may also be useful to describe additional aspects of ourselves, such as brain features, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Sliding scales thus provide a flexible means to represent more accurately the complex combinations of traits that we all embody.

References

1. Fausto-Sterling, Anne. (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York, NY: Basic Books.